I’ve wanted to write about Wanda Gág’s art and children’s books for years, but my affinity was too overwhelming to put into words. How could I pick one thing to focus on when there was so much I was attracted to? Plus, every time I tried to write about Gág’s art, I found myself writing about Gág, the woman—I couldn’t extract the two. Then I realized this was exactly what Gág wanted: unity between her life and her art. Why was I fighting it so hard? Still, I had to find a way to convey the connection. I contemplated many images and poured over her diary entries, thinking about art, about objects, about symbols and language. I collected fragments of oblique relations and put them beside each other, but there was no real argument, and to create one felt forced. Then I discovered Chloe Aridjis’s alphabetical portrait of the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, for the London Review of Books. It showed me that I didn’t have to string together a story; I could compile episodic moments, words, phrases, discoveries, feelings—not arbitrarily—but through the constraint of an alphabetical sequence. And it turns out, there is a connective thread that weaves this list together: Gág’s attunement to rhythm. Her sensitivity and attention to the rhythms of nature, objects, color, and sound was dazzling and definitive—the absolute form of imagination. While this portrait is not meant to convince you of anything, or teach you about children’s books, I hope it produces an effect, and inspires you to learn more about Wanda Gág and engage with her work.

To echo Gág’s words she wrote in a letter to the famous photographer Alfred Stieglitz:

“I like much of what you are—and what you do—all one.”

ABC Bunny: After publishing three successful picture books that shared a striking visual unity (Millions of Cats, The Funny Thing, Snippy and Snappy), Gág wanted to try something new. Instead of creating a simple alphabet sequence, she decided to write The ABC Bunny (1933), a story of a young rabbit, utilizing the letters in creative ways. She illustrated it with lithographs on zinc plates printed offset in large format. Like many of her children’s books, Gág involved her talented siblings, asking her brother, Howard, to render the hand lettering, and her sister, Flavia, to write the ABC Song. It proved to be one her most ambitious and challenging projects, but the end result is an exquisite example of Gág’s innovative bookmaking.

Books: When Gág wasn’t drawing, she was reading. Her love for stories and language are evident even in her early diary entries, where she casually mentions reading Shakespeare, Chaucer, Chantecler, Vanity Fair, and Truxton King. Some of the other authors she mentions: Ibsen, Hugo, Dostoevsky, Shaw, Sudermann, Browning, Tolstoy, Thoreau, Tagore, Whitman, and Voltaire.

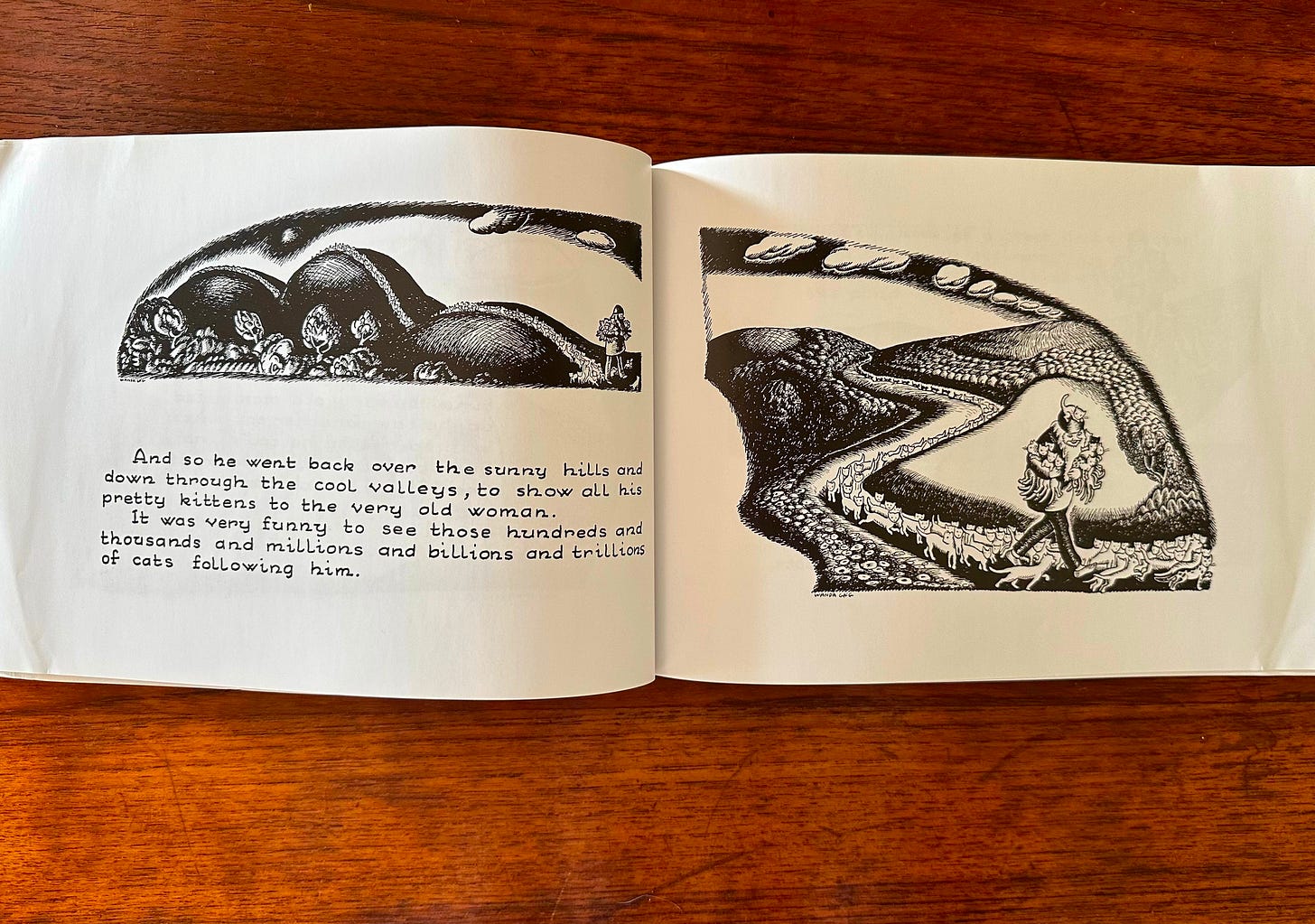

Cats, millions of them: In 1928, Gág published her first and most famous book, Millions of Cats. It’s a fairy tale story of a lonely old man who sets off to find a cat companion for him and his wife. But instead of one cat, he comes back with “hundreds of cats, thousands of cats, millions and billions and trillions of cats!” Unable to choose just one, he decides to keep them all, that is, until his wise wife reminds him the cats will eat them out of the house and home. They decide they will keep the prettiest cat, but let the cats choose who that is. Chaos ensues! The cats quarrel and, presumably, eat each other up because they all disappear—except for one homely little kitten. The old man and woman take it in, and with a little love and care, the kitten turns out to be very pretty indeed.

It may seem common now, but Millions of Cats was a revolution for children’s books. Not only did it reject the maudlin and sticky sweetness of the children’s stories that dominated that era, it also changed the way we engage with picture books as objects by telling a story through the interplay and animation between text and image across a double-page spread. (Jump to the letter “P” for more on this.) Gág recognized that a book’s design informs the entire storytelling experience.

Desire: a word that encapsulates Gág as an artist, woman, and human.

Desire, desirous, desirable.

Urge, longing, craving, thirst, hunger, passion, appetite, yearning.

A strong feeling of wanting to have something or wishing for something to happen.

Gág often juggled several romantic partners at the same time and was open about them. She believed that love affairs helped her drawings and were necessary for artistic rebirths. She disagreed with people who criticized open relationships.

When thinking about people like her, she writes, “It’s not necessarily a desire for promiscuity which causes them to have several affairs. It’s often uncomfortable and distressing to abandon the old ruts, the familiar habits, the security of a well-established relationship. On the contrary it usually requires a good deal of courage.”

Sex was important to her, especially for her artistic vitality. Whether you agree with Gág’s personal life or not, you can’t deny that her feeling for rhythm—by pencil, by brush, by ear, by body—makes her an alluring artist.

“I’m about ready for a renaissance. Book illustration’s all right—I’m in a strong position there, luckily, and can do just about what I please, and of course, it’s what I’m living on—but what I like to do best of all is to make myself receptive to the rhythm and forms about me and to record them in an intense yet logical a way as I am capable of. My dear owner of a glorious thermometer, you have a feeling for rhythm, you understand the architecture of Liebes Spiel1—a drawing in my estimation should be very much like this, built up sensitively, logically, inevitably. This is what your countryman Goya2 knew how to do but Zorn3 did not.” (Gág in a letter to Hugh Darby, 1993)

Gág was preoccupied with drawing fireplaces, so much so that she wrote in her diary that she had to stop. Actually, a fireplace is a good metaphorical image for Gág, with its dazzling flames safely contained in deep rich shadows. You can’t help but think, if she wasn’t so disciplined, she could have easily blazed out of control. Her fiery passion for art, humanitarianism, sex, love, and recognition, lit her from within, and whenever she felt that fire begin to fade, she would do anything to reignite the flames.

She wrote in her diary,

“But there must be fire!”

Emperor, Pope, God: In the Grimms’ fairy tale, The Fisherman and His Wife adapted by Gág in Tales from Grimm (1936), a poor little fisherman and his wife live in a vinegar jug by the sea. When the husband catches a magical talking fish who begs to be released back into the sea, he obliges, but when his wife discovers this, she insists he return and ask the enchanted fish a wish: a hut for them to live in.

Manye, Manye, Timpie Tee,

Fishye, Fishye in the sea

Ilsebill my wilful wife

Does not want my way of life

When her wish is granted, she then asks for a mansion. This pattern continues, each time her wish is granted, she becomes greedy for more, wishing to be a King, an Emperor, a Pope. Eventually she asks to be like God, but this time, when the fisherman runs to meet the fish, there is a huge storm, the sky is pitch black, and big violent waves crash onto shore. When he yells his wife’s wish to the fish, the fisherman and his wife are returned to the vinegar jug where they live for the rest of their lives.

What do you think? Did she get her wish?

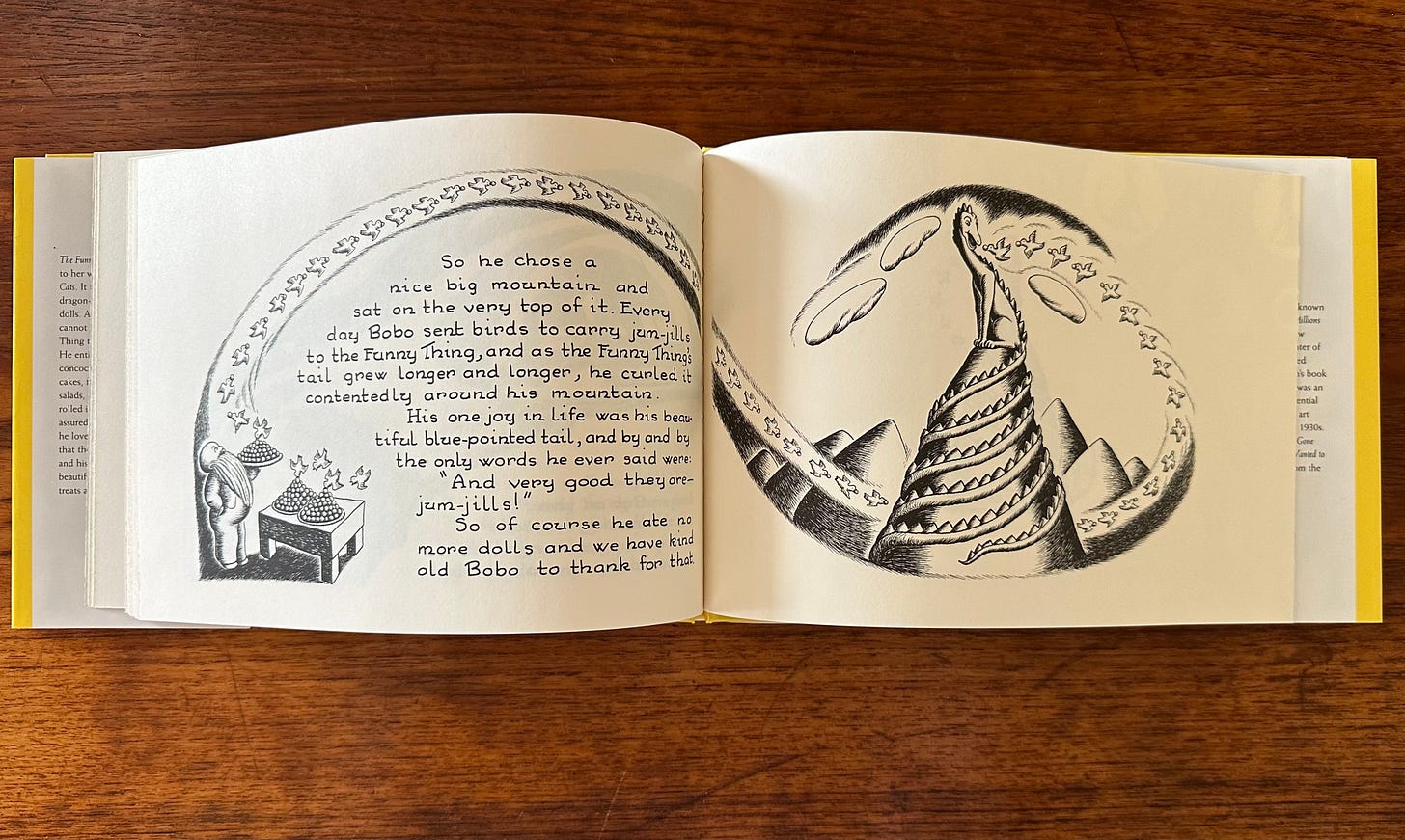

Funny Thing: My favorite Gág book! Published in 1929, The Funny Thing tells the story of a kind little man named Bobo, who lives in a cozy den in the mountains, and spends his days feeding animals tasty foods. It’s all very sweet and cute, with nut cakes for the fuzzy-tailed squirrels and seed pudding for the pretty birds and tiny cheeses for the little mice, until one day a dragon-like creature called the Funny Thing arrives and refuses Bobo’s yummy treats, demanding a meal of children’s dolls! Bobo, aghast and upset, devises a plan to trick the Funny Thing into eating something else: a recipe of all his ingredients mixed up into soft, round little balls he calls jum-jills. Bobo tells the Funny Thing (who’s incredibly vain) that they will make his blue spikes more beautiful and his tail longer. With foolish eagerness, the Funny Thing eats one jum-jill after another, day after day, as his tail grows longer and longer, forgetting all about eating dolls. It's a deliciously strange story, and like Millions of Cats, it’s a beautiful object, with hand-lettered text and enchanting illustrations attractively laid out across double-page spreads.

Grimms’ Fairy Tales: Gág grew up with the magic of Märchen (German for fairy tales, folktales, fables, legends—oral storytelling). In her compelling introduction to Tales from Grimm, she writes of her childhood, sitting cozily in her rocking chair, at twilight, eager to listen to a good story. She describes the feeling that flooded her as she abandoned herself to the tale as a “tingling, anything-may-happen feeling…the sensation of being about to bite into a big juicy pear.” Those sensorial storytelling experiences stayed with her into adulthood. She could feel her way into a story, through visual and auditory reactions to words. This skill helped her create one of the best, if not the best, English translations of the Grimms’ fairy tales, for any age.

Gág wanted these stories to be clear in ways that children could better understand them. She simplified confusing passages, used repetition for clarity, and included dialogue to help sustain interest. But Gág did not believe in writing down to children. She kept large, unfamiliar words for color and sound-value. The result is prose distilled to its purest flavor, sublimely arranged, and rich in symbolism—a syntax of life.

Hotbed of Feminists: An inspiring essay written by Gág anonymously for an ongoing series “These Modern Women” in the June 1927 issue of The Nation. Gág was an early-feminist thinker, who pulled herself and siblings out of poverty through hard work and a steadfast belief in her artistic talent.

Ideas: Gág kept a “Notebook of Ideas” for stories (some were published, many were not), such as Bobo, The Funny Thing, Snippy and Snappy, The Horse Radish, Tiger Lily, Fountain Penguin, and Alice in Blunderland.

Jum-jills (little cakes in The Funny Thing), Treetop (sex), Ovals (drunk), Linga (male sex organ), Youri (female sex organ)—some of Gág’s made-up words.

At the back of her Tales from Grimm, Gág included a “In Case You Want to Know: The Meanings and Pronunciations of Unusual Words in This Book.” Some are German words and phrases, but there are also strange words that are more about sound and mouth-feel, than meaning—like Timpie Tee. Gág writes:

“In a way it doesn’t mean a thing—that is, it’s not a dictionary word—but it’s a magic word, so you see it’s very important, all the same.”

Kent, Rockwell: Gág’s social circle was very impressive. In her diaries, she casually mentions going to parties with other artists like Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, and she was friends with Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, but her relationship with Rockwell Kent piques my interest most—not for any big reason—they weren’t, as far as I know, romantically involved, and they didn’t seem to be particularly close. However, they had mutual respect for each other’s artistic style (which happened to be similar), and they, at least for one night, shared a flirtation on the dance floor.

Gág’s diary entry of their first encounter is brief but thrilling. In 1923, while at the Playboy Ball, she met a man with whom she danced and got along with “unusually well.” She soon finds out that he’s the artist Rockwell Kent. He showers her with compliments, telling her she’s wonderful—as a dancer—calling her moves “like steel” and “like wire.” Despite his befuddling statements, she was pleased, believing he’d noticed her “tense flexibility.” She felt it was possibly the nicest of dances she’s ever had.

But the best part of this little anecdote is the end, Gág writes:

“Rockwell Kent rolled his eyes at Wanda Gág, and Wanda Gág gave Slavic looks in return! And my cheek lay against his, but best of all—we expressed the music mutually and simultaneously.”

I like to imagine this scene: Wanda Gág and Rockwell Kent, both a little drunk, communicating to one another without words, but through body language. Their dancing, like their art, shared a similar rhythm and style, and I think, they recognized it, and even though they never consummated their relationship, they felt an electric charge (and probably some competition) between them throughout their friendship and careers.

Kent wrote in praise of one of Gág’s exhibitions:

“Yield yourself to what is here, for it has the power to profoundly move you.”

I can’t help but think he’s talking about more than just her artwork.

Lithographs: Gág was a prolific printmaker, producing more than 100 beautiful lithographs, woodcuts, and other types of prints.

Me and Myself: Before Freud, there was Gág. In her early 20s, Gág developed a theory that a person is made of two conflicting selves: Me and Myself. Me is the unstable self, the part of you that’s always fluctuating between need and desire—your outer self. Myself is your permanent, true self—your inner self. Throughout her life, Gág yearned to fuse her two disconnected selves into one harmonious whole, and yet she knew it was only possible in momentary flashes of enlightenment. Most of the time it was about self-acceptance.

She wrote in her diary in 1914:

“There is nothing better for us to do than to take ourselves as we find ourselves and make the best of ourselves.”

Nature: Gág found city life draining and overstimulating; she preferred the countryside. She believed being close to nature improved her art (which it did). She studied the natural world intensely, absorbing its essence, paying close attention to the poetry of trees and clouds and flowers. Her vivid landscapes wobble and quake with a pulsating energy; they feel alive.

Objects: Gág had an affinity for objects. She was highly attuned to their secret vibrations, their mysterious rhythms of form and color. Her sharp perception of the undercurrents of the not-quite visible gave shape to the atmosphere around objects. She was determined to illuminate the mysterious ways in which objects respond to other objects, and give form to the geometric and carefully calculated distance between them. Her theory is fascinating.

In her diary entry on February 14, 1928, she writes:

“I tried to explain to him {Carl Zigrosser}, as I have before, what I was trying to do with the atmosphere around objects. To me, sometimes, an object projects repetitions of its own form into the surrounding atmosphere, and in a way space achieves a three dimensional quality.”

“I want to show the volume of atmosphere, its essential form as related to (or rather produced by) the objects it surrounds. Furthermore, there is the inter-relation of these atmosphere forms and rhythms as created by the interrelation of a group of several objects. Well, it’s all very difficult, but it’s pretty definite in my perceptions. For instance, in drawing an interior, I am not only interested in drawing objects which are conversing as to form and weight—the cubical character of a trunk, the squareness of tables, cylindrical quality of a lamp chimney, the flatness of walls, the spherical quality of fruit, the discs of flowers, etc.

But what about the negative forms which are produced by the presence of these several objects?…There is to me no such thing as an empty space in the universe—and if Nature abhors a vacuum, so do I—and I am just as eager as nature to fill the vacuum with something—if nothing else, at least with a tiny rhythm of its own, that is a rhythm created by its surrounding forms.” (diary entry October 29, 1929)

Picture book: The modern picture book that we know and love, started with Gág. Prior to Millions of Cats, illustrations were mostly decorative, and were typically placed on one side of the page, while the text was on the other. Gág was the first to compose two facing pages into one double-page spread, combining the illustrations and the text. She also helped define the art form as one in which a single artist conceives, writes, illustrates, and designs the whole book.

She treated her books for children with the same diligence and respect as her other works of art.

“I aim to make the illustrations for children’s books as much a work of art as anything I would send to an art exhibition. I strive to make them completely accurate in relation to the text. I try to make them warmly human, imaginative, or humorous — not coldly decorative — and to make them so clear that a 3-year-old can recognize the main object in them.”

Queen: In Gág’s translation of the fairy tale Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1938)—which Anne Carroll Moore4 prodded to her write and illustrate in response to the water-downed Disney adaptations—she stayed close to the Grimm version, using the term “Queen” for the king’s second wife, rather than “Stepmother” which can be found in many of the 19th-century versions. 5

Rhythm: "Perhaps I worship rhythm as some worship the sun, or god, or the body. Rhythm in my consciousness, becomes a broad term. I use it daringly, no doubt…All about me there is a glorious fitting together of things, round, smooth faces with corresponding sockets; sharp painful angles with their complementary shapes; long vivid jags into crevices that hold them perfectly and calmly, so to restore the equanimity and rightness of things; and most of all perhaps, long tendrilly jutterings-out to receive and organize all the helpless fringes and frayed edges of our groping lives. From these abstract manifestations emanate actual projections such as works of art, dancing, musical compositions, rare ecstasies, individual actions, reactions and decisions, the relation between two well-matched people, and for some forms of literary expressions such as some sonnets and certain passages from Keats or Shelley. Well, I suppose this is nothing more than imagination gymnastics. But it’s been fun to build it all up just as it’s fun to build up a fantastical drawing.” (Letter to Adolf Dehn, December 1921)

Snippy and Snappy: Gág’s third picture book, published in 1931. The title was inspired by her close friend, gallery manager, and influential art dealer, Carl Zigrosser, who called her “Snappy Eyes.” The story, along with The Funny Thing and Millions of Cats, is included in Wanda Gág’s Story Book (1932).

Transition: I’m drawn to coming-of-age stories: the transition from adolescence to adulthood, navigating the challenges of identity and self-discovery, the emotional struggle and complexity—it’s excruciating but also exciting.

Actually, as a woman experiencing the transition into middle-age, I feel like I’m in the midst of a coming-of-age story, and I anticipate another one around age 60. Reading Wanda Gág’s diaries, I relate to her many transitions. They give me a better sense of how these tumultuous phases in life affect creativity. It helps me feel less alone.

Unusual: Gág always felt unusual, but was proud of her individuality. She never wanted to be anyone but herself. This steadfast belief in her uniqueness sometimes hurt her, financially and personally. Throughout her career, she turned down many opportunities because they didn’t live up to her standards, and when she did make sacrifices for the sake of money, it caused her a lot of grief.

She wrote in her diary in May of 1924:

“I don’t want to be a second Anybody. I want to be myself. Perhaps I am too radical. Too radical, perhaps, for one who needs money badly. I don’t know whether I have too little sense to conform to to these things, or too much sense.”

Visual style: Exuberant, profound, tense, rhythmic and whirling, with vertiginous currents of time and space, in which everything unfolds in a slow hazy fog and, simultaneously, with rapid speed, a “tense flexibility” brimming with possibility, giving shape and story to movement.

Words: Gág loved language, but felt frustrated by its limitations. In 1923, she wrote in her diary:

“I felt that the dictionary, although containing many words, was sadly lacking in the right one. And it lacks one in particular, and that is the modern word for love. I refuse to consider myself in love with anyone. There should be a word which includes, or is composed of:

Intellectual companionship

An intense but flexible affection

Honest, wild, animal passion

A sense of humor which is not hampered with idealistic and impossible notions of smotherings of romance.

I mean a certain kind of romance, for there are kinds which I do not disdain, or perhaps I should say I do not object to romantic situations if they are approached in the right frame of mind, that is—either very recklessly or analytically or whimsically. Webster should have had a Slavic lady to help him fix-up his dictionary.”

MiX: “I must make myself the centre, and remember that the wisest thing to do is to keep myself in a position to be combined, dissolved, re-combined, re-dissolved, and so on…Wanda Gág’s groupings for a unison between art and life.” (diary entry May 18, 1922)

You: “I like you because you are Wanda.” —Adolf Dehn (diary entry, July 15, 1916)

“I think it is necessary for me to be bad for a while—the aesthetic value of sin is not to be sneeZed at.” (diary entry, May 18, 1922)

The Moonbow Membership

This article will be free to read for a short period, but then it will be added to the Moonbow archive for paid subscribers, where there are pieces on children’s authors like James Marshall, Tomi Ungerer, and Margaret Wise Brown, and essays and reviews on new picture books like There Was a Shadow, The Skull, and the Chirri and Chirra series. Moonbow members also get full access to FAQs (next one coming soon), the picture book club meetings (next one coming soon), and get special perks in the mail (because who doesn’t love snail mail).

Writing these articles is tough but rewarding work. If my time, ideas, and research is valuable to you, please consider becoming a Moonbow Member. It’s only $5 a month! If that’s not possible, liking and re-stacking my articles are other great options.

With gratitude,

Taylor

Acknowledgement: Thankfully, there are a lot of great resources available on Wanda Gág, and I used many of them to write this. However, most of them are limited. I wasn’t able fact check or dig deeper on some of these fragments because they’re a part of the Wanda Gág’s papers, which I don’t have access to (maybe one day!). If you see anything that needs correcting, please feel free to message me.

These three books were helpful resources: Wanda Gág, Growing Pains: Diaries and Drawings by the Author of Millions of Cats (1940), Wanda Gág by Karen Nelson Hoyle (1994), and Wanda Gág by Audur H. Winnan (1993).

You may also like:

“Liebesspiel” is German slang for “lovemaking”

The Spanish artist Francisco Goya (1746-1828)

The Swedish artist Andres Zorn (1860-1920)

Anne Carroll Moore was a pioneer in children’s librarianship, and was hugely influential in children’s book publishing in the first half of the 20th century. She famously hated Goodnight Moon.

Wanda Gág by Karen Nelson Hoyle (1994)

I can relate to being so enamored with something that you want to cram every fact and thought about it into one piece, at the risk of putting your reader to sleep and also still not being satisfied 😂. (I’m kind of in that boat at the moment.) I think your A-Z approach was the perfect answer. And you’ve definitely made me an even bigger Wanda Gág fan!

So wonderful! And I'm struck at how little I knew about her despite Millions of Cats being one of my lifetime most read and beloved books. I'm excited to dig in deeper.

So, I imagine you're already in the know on this, but the Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota has a massive archive of her work and correspondence: https://archives.lib.umn.edu/repositories/4/resources/3507

And, more generally, they have funding for researchers available sporadically... :-)