Margaret Wise Brown and the Art of Paying Attention

In her books for children, Brown used poetic soundscapes and surprising metaphors to expand our ideas of what it means to be human.

“A book can make a child laugh or feel clear-and-happy-headed as he follows a simple rhythm to its logical end. It can jog him with the unexpected and comfort him with the familiar, lift him for a few minutes from his own problems of shoelaces that won’t tie and busy parents and mysterious clock-time, into the world of a bug or a bear or a bee or a boy living in the timeless world of story. If I’ve been lucky, I hope I have written a book simple enough to come near to that timeless world.”—Margaret Wise Brown

Read the acclaimed children’s author Margaret Wise Brown enough times, and you’ll start to notice themes, or maybe preoccupations is a better word for them—the night, rabbits, dogs, celery, sunrise, the moon—these are just a few of her enthusiasms. As a writer and poet, Brown was uniquely adept at paying attention to the things of the world but also to our inner worlds, our sensations. The sonic texture of her words awakens the senses, bringing awareness to abstract thoughts and feelings. Her poetry opens up small moments, creating space for expansion—suddenly, the reader sees, hears, and feels things with more depth and perplexity. She notices the “blue nights with a foggy moon, smoking in the trees” and pauses to remember “the ticklish sneezing smell of a hot daisy.” Her gift was finding constellations of surprise in ordinary, everyday moments.1

The poet Jane Hirshfield wrote that poetry “takes place in the border realm where inner and outer, actual and possible, experienced and imaginable, heard and silent, meet. The gift of poetry is that its seeing is not our usual seeing, its hearing is not our usual hearing, its knowing is not our usual knowing, and its will is not our usual will. In a poem, everything travels both inward and outward.”2 Brown’s poetry exists in the border realm; it straddles the edge of perception, where our conscious and unconscious thoughts swirl together, like in a dream. It shines a bright light on beauty while digging it up with a pitchfork. This is also the job of children. The philosopher William James described the world of children as “buzzing and blooming confusion.” They inhabit the strange in-between space of knowing and not knowing, paying close attention to wonder—dissecting it under a microscope. They are experimental observers searching for answers, which is why they’re such natural poets.

“Here is the playful audience of James Joyce and Edith Sitwell and Gertrude Stein, the audience of Virginia Woolf and Swinburne and the King James version of the Bible. Translate their playfulness and serious use of the sheer elements of language into the terms and understandings of a five-year-old and you have as intelligent an audience in rhythm and sound as the maddest poet’s heart could desire.”

—Margaret Wise Brown, “Writing for Five-Year-Olds” (1939)

For children, reading is a bodily experience. They read with their senses, whereas adults read with their eyes. They respond to the rhythm and sound of words. In Brown’s essay, “Writing for Five-Year-Olds,” she writes that the pleasure of reading for children is in the melodious rhythms of the spoken word. “It is a distinct form of prose writing, more rhythmical in its pounding, flowing lines than the words that are written for the eye.” But it’s not just about sound; content is also important. Children’s literature should have a close connection between rhythm and content. It should meet children where they are in development and experience. It should include their delights and interests, the things they pay attention to.

Children are intuitively skilled at paying attention—which was also Brown’s superpower. As a child, she spent most of her time outdoors chasing butterflies, cloudwatching, and adventuring through the nearby forest. Imagining young Margaret meandering through grassy meadows, quietly gazing at the miraculousness of a daisy, makes her seem twee, like Alice from Alice in Wonderland. Brown was a wildly curious dreamer, but sometimes she could be more like the Queen of Hearts—with a fiery, capricious personality prone to mischief and temper tantrums. Other times, she was more like the erratic, eccentric, and exasperating Mad Hatter. But Brown needs no comparison; she was wonderfully unusual and unapologetically herself.

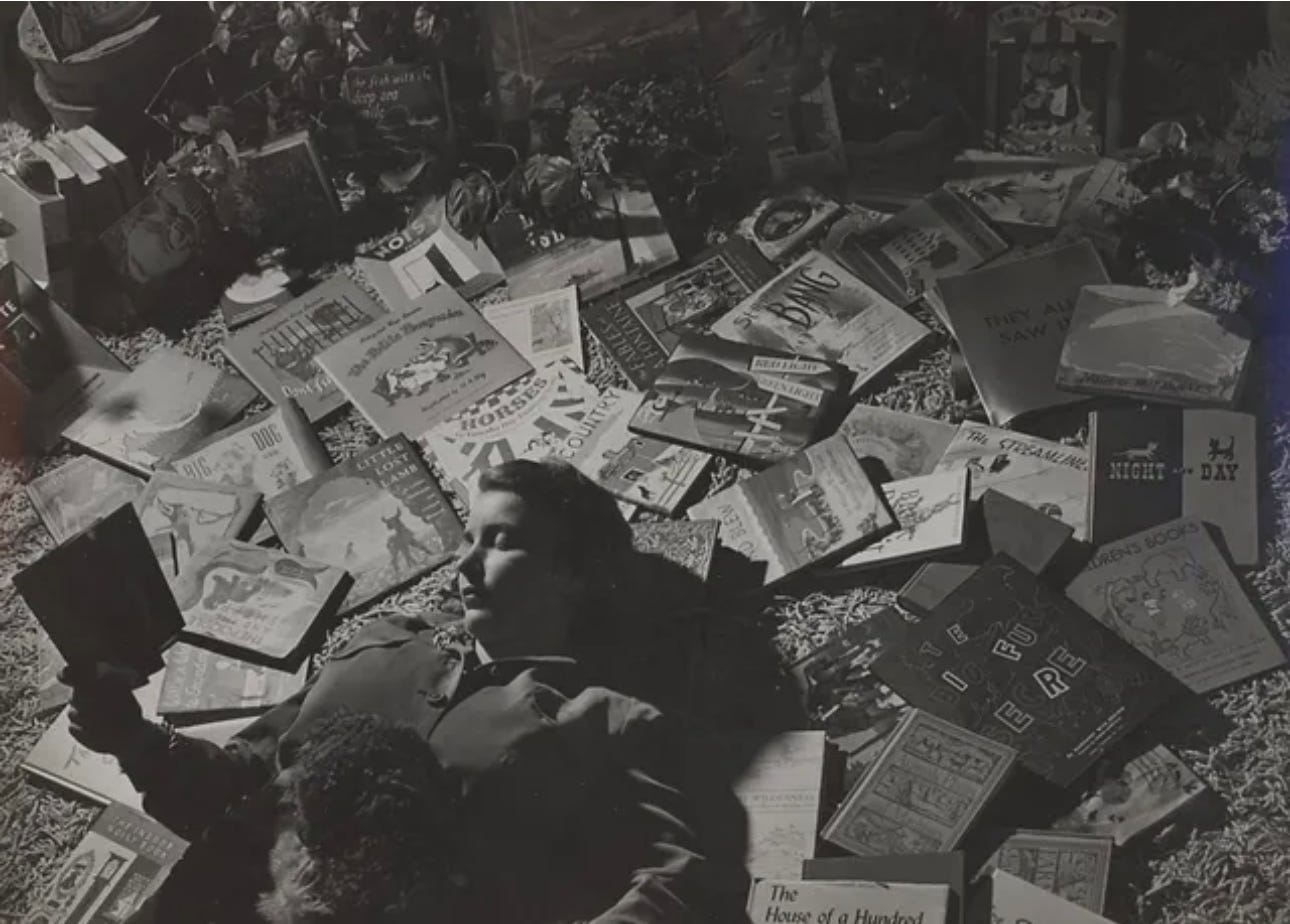

Growing up, Brown was exposed to a variety of books, everything from fairy tales to National Geographic. Her hunger for knowledge was voracious. She kept records of her findings in her childhood diary, fusing lines of poetry and songs with daily observations of the weather and the moon’s phases. She also read books out loud to her younger sister Roberta, rewriting the story as she went along—adding surprising twists and turns to keep her listener rapt. These early textual experiments were foundational to the imaginative writing Brown would become known for.

In the early ‘30s, after graduating from college with an English degree, Brown began writing short stories, but she struggled to develop traditional plots. Frustrated and disheartened, she moved to Manhattan, where she enrolled at Bank Street, a progressive college for student teachers. She quickly discovered she wasn’t a great teacher, but her mentor, Lucy Sprague Mitchell, recognized Brown’s Mad Hatter poetic genius and encouraged her to try writing for children. Mitchell believed that children’s stories should include something familiar, something they recognize—and that children respond more to the sounds of words than they do their meanings. For them, words reflect the immersive world of the sensory realm: the sights, sounds, smells, and feelings—the Here and Now of their everyday surroundings. She felt children’s stories should look and sound like the lived experiences of childhood, not a romanticized version by jaded adults. This idea directly opposed children’s literature at the time, which was mainly fairy tales, myths, nursery rhymes, and moralistic fables. Brown was attracted to Mitchell’s unusual approach but never fully endorsed it; she was too original to be tied down to one doctrine. Instead, she combined the Here and Now with poetic language and traditional storytelling techniques, creating something entirely her own.

Brown’s understanding of the Here and Now was more nuanced than Mitchell’s. She saw it as an imaginative experience—a constellation of sensations, feelings, and thoughts children synthesize through creative play. It’s part reality and part fantasy, swirling in a hazy blur. And she was determined to create stories that emulated this ever-shifting kaleidoscope view of the world.

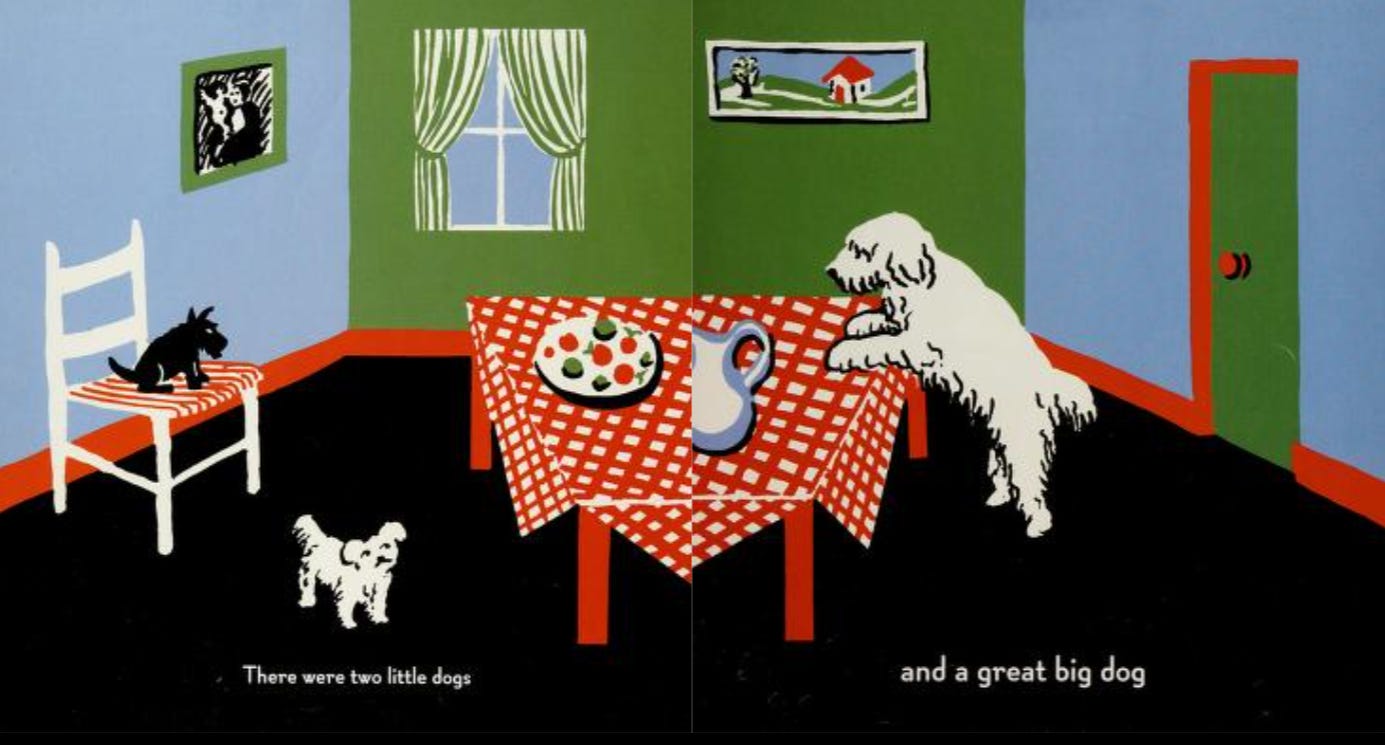

She approached writing like a science experiment, constantly tweaking her formula. One of her first picture books, Bumble Bugs and Elephants (1938), illustrated by the modernist artist Clement Hurd, resulted from trial and error. There is no plot; instead, it starts like a traditional fairy tale with “once upon a time” and then unexpectedly lists a series of large and small creatures living alongside one another in a rich, colorful world familiar to children. There are gardens, butterflies, tugboats, and a dining room. There’s also a simple, repetitive pattern to the text—after a few pages, children know what to expect. But then Brown and Hurd throw another curveball with a blank spread and the question, “What do you know that is great big?” Turn the page, and another blank spread asks, “What do you know that is tiny little?” Suddenly, the story opens up, inviting the reader to step in and write their own ending. This surprising technique became a defining characteristic of many of Brown’s books.

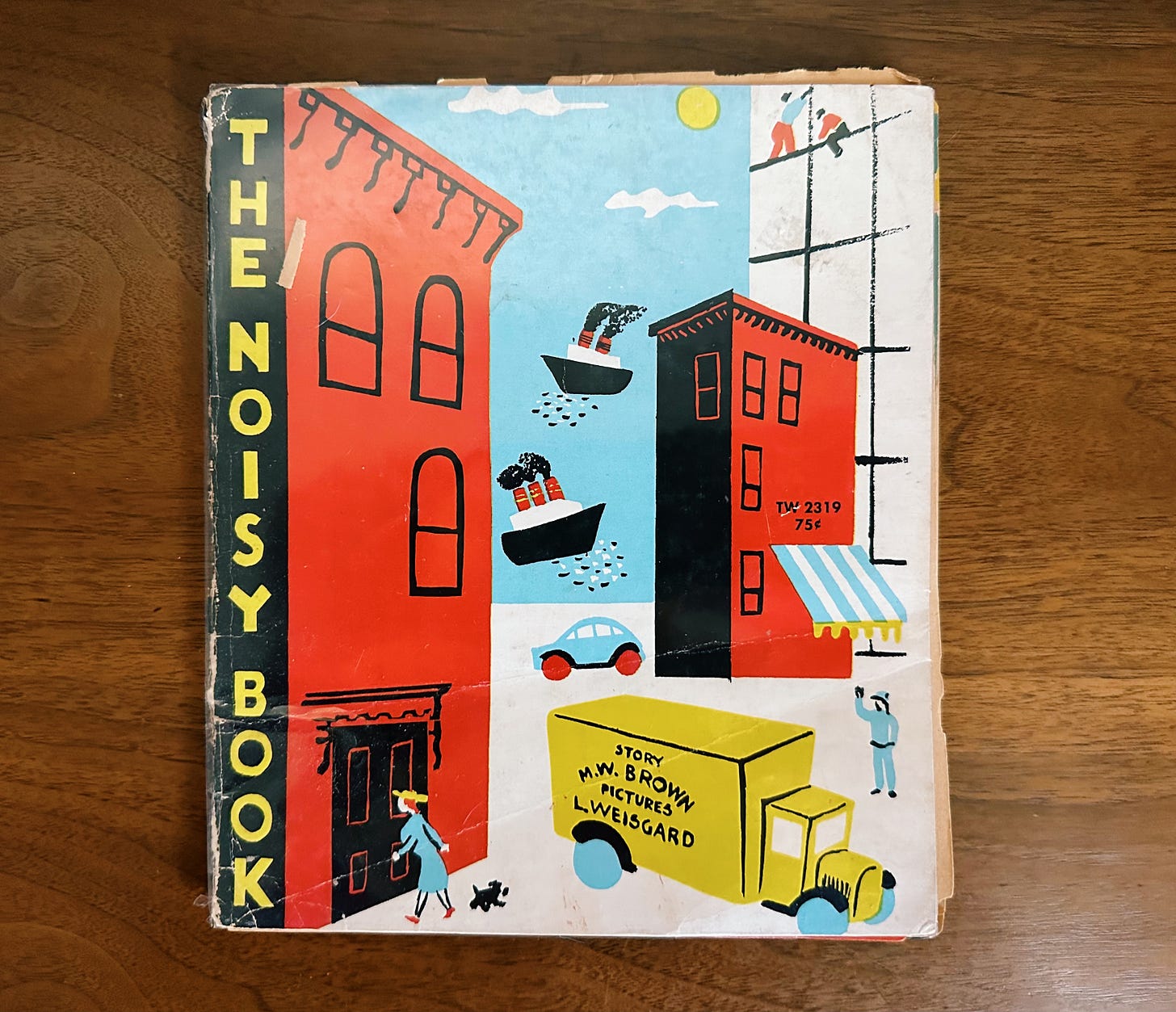

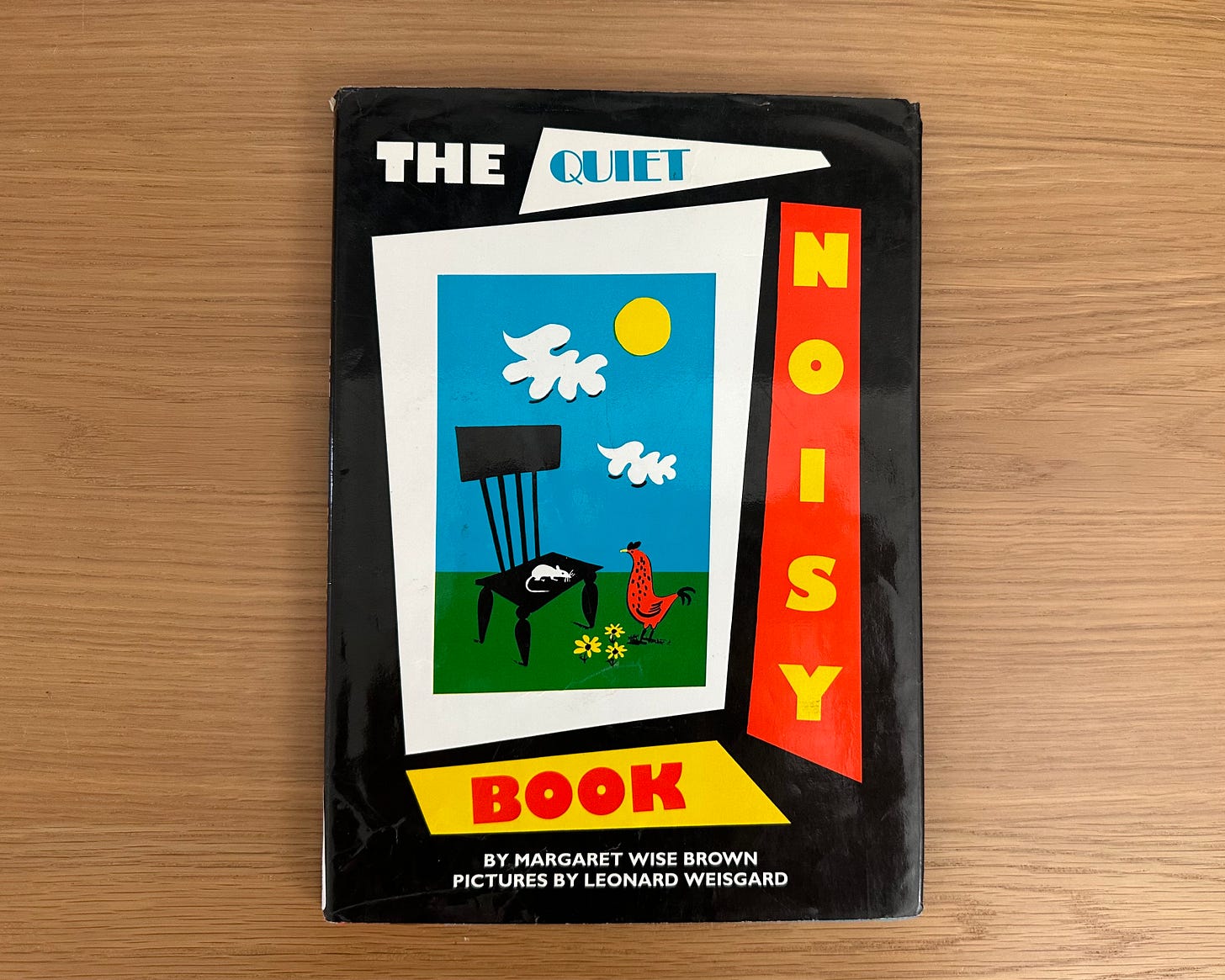

Brown continued to experiment. In The Noisy Book (1939), illustrated by Leonard Weisgard, she created a playful, here-and-now-game-like narrative that encourages readers to participate in a sensory exercise. It’s the story of a young dog named Muffin who is temporarily blinded and has to wear a bandage over his eyes, forcing him to rediscover the world through a heightened sense of sound. The book is a raucous read-aloud that tests the limits of vocabulary while pushing the limits of imagination. It requires the reader (the adult) to emphasize the sound of words rather than their meanings, and it directly asks the listener (the child) to inject their imaginative interpretations of words and sounds. Brown’s circular spirals of repetition and rhyme, combined with Weisgard’s use of color, scale, and surprising page-turns, disrupt expectations and challenge preconceived notions of sound. Louise Seaman Bechtel, a renowned children’s book editor and critic, wrote in awe of The Noisy Book, “…children are all attention for a book they have to talk back to.”3

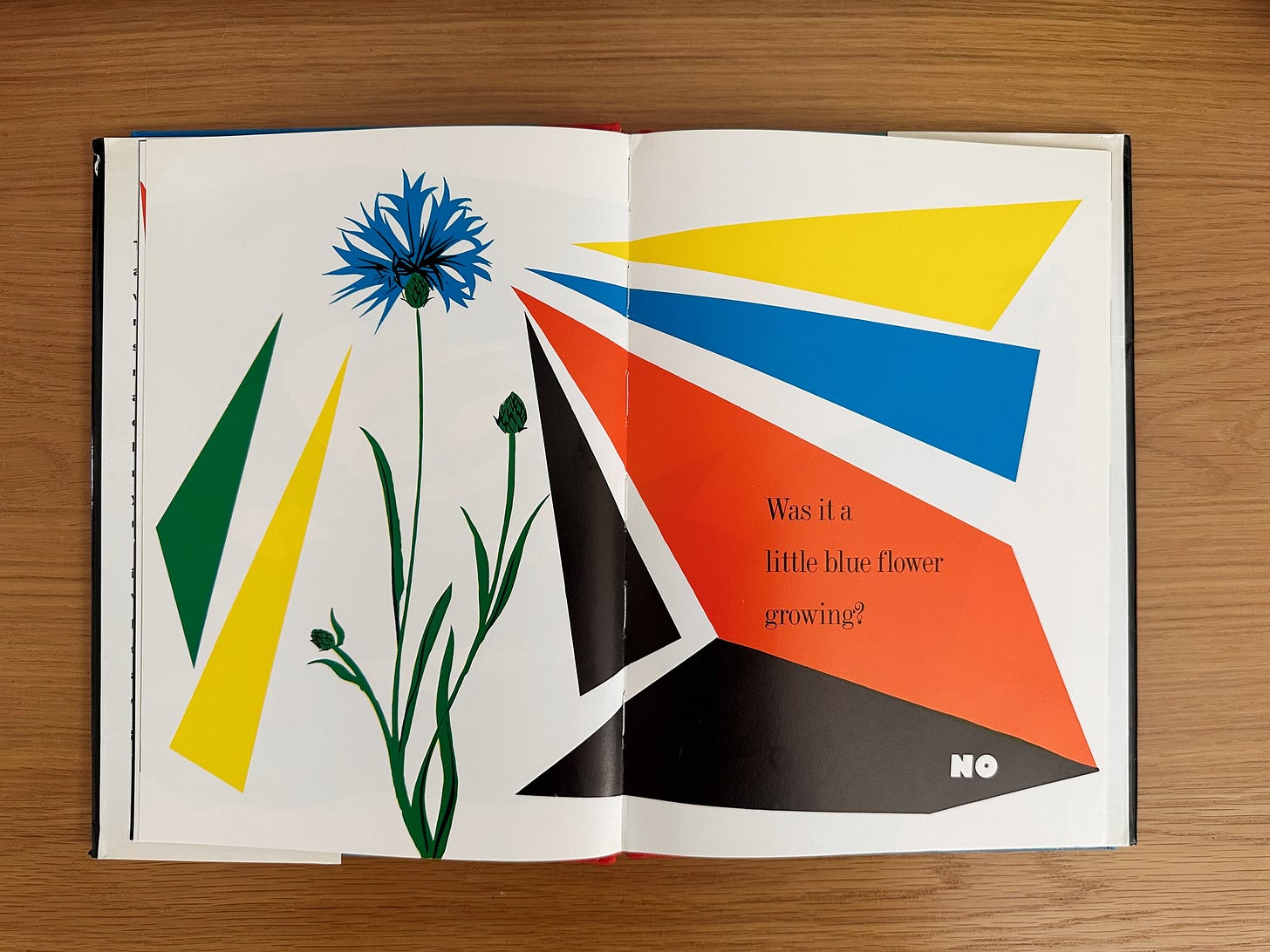

Can you hear the sun shining? A bee wondering? A little blue flower growing?

These are some of the riddles of sound Brown asks children to imagine in The Noisy Book and subsequent follow-ups, such as The Summer Noisy Book (1939), The Indoor Noisy Book (1942), and The Quiet Noisy Book (1950). Children must think metaphorically to “solve” the riddle, which they do naturally, unlike most adults. But in these books, children and adults must playfully work together, using their senses and imaginations to give words a way to go beyond their meanings.

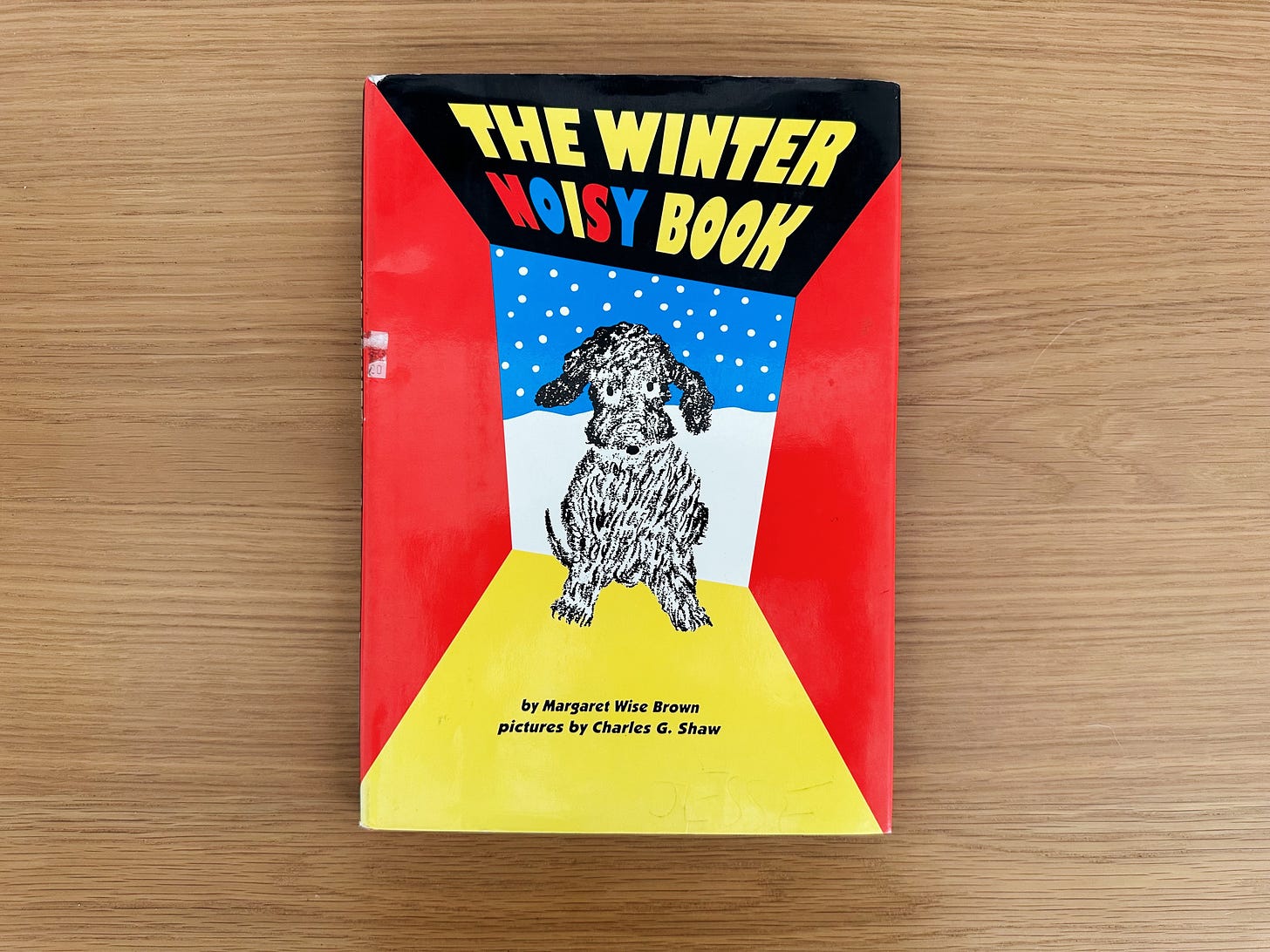

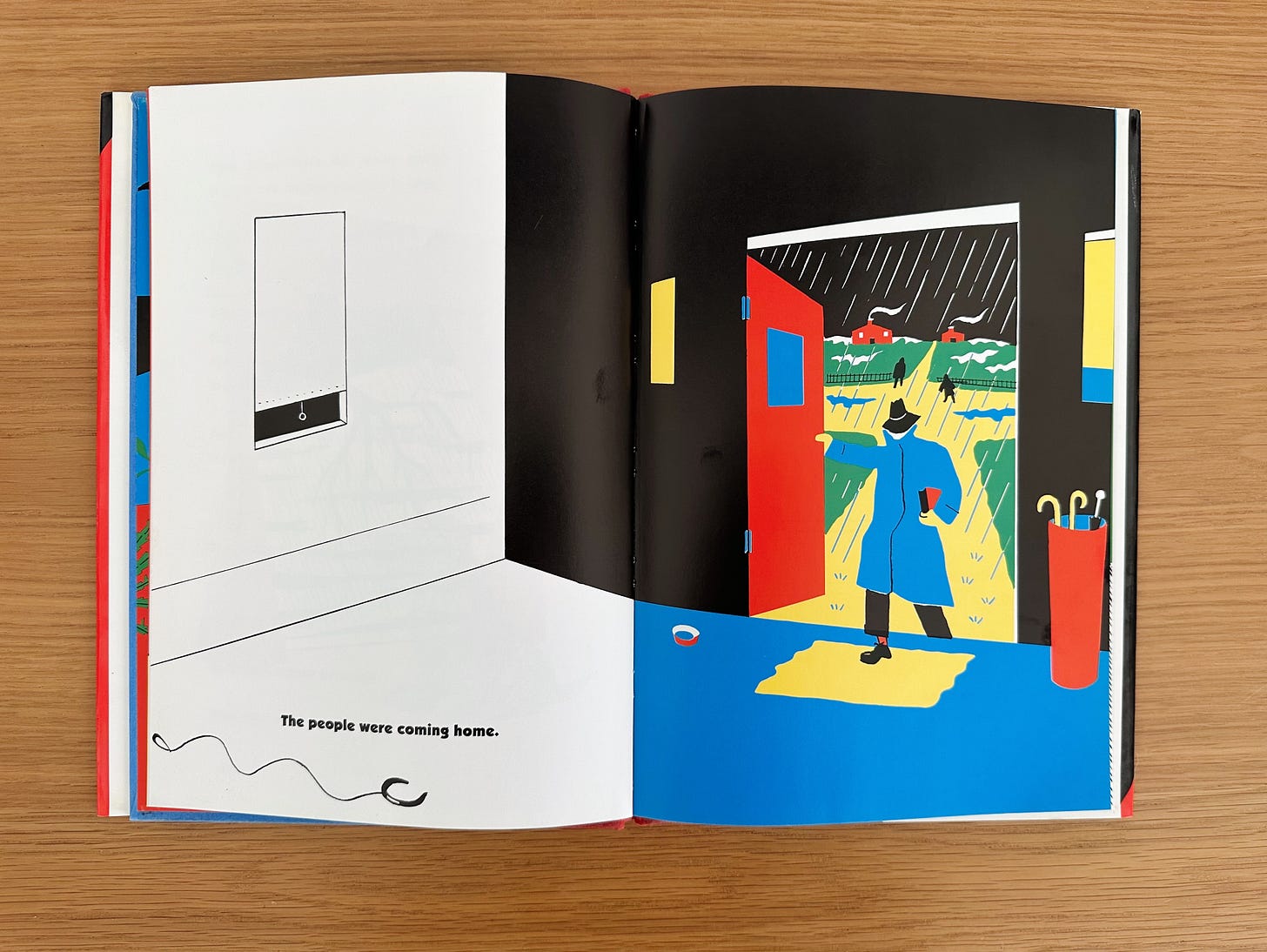

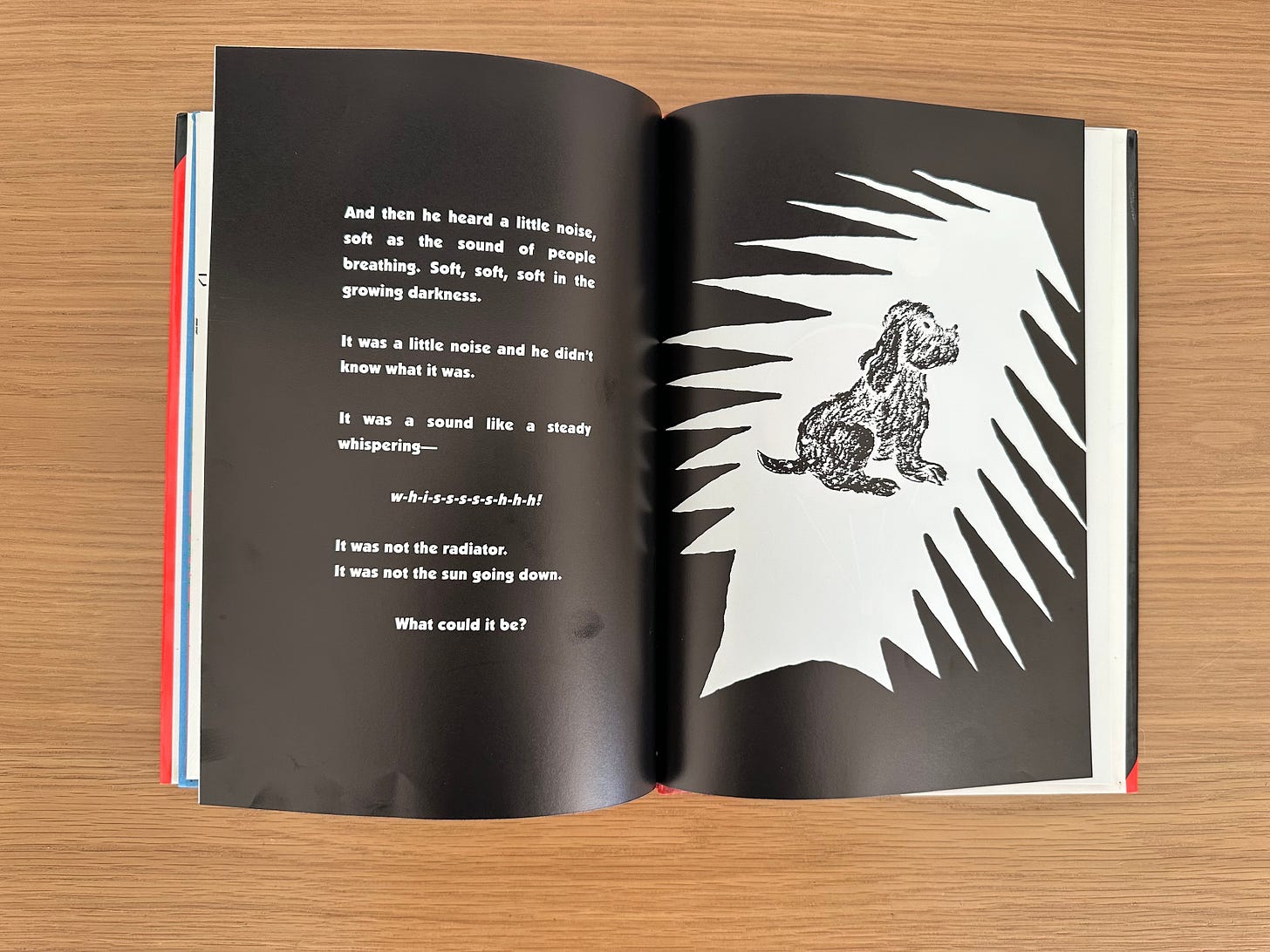

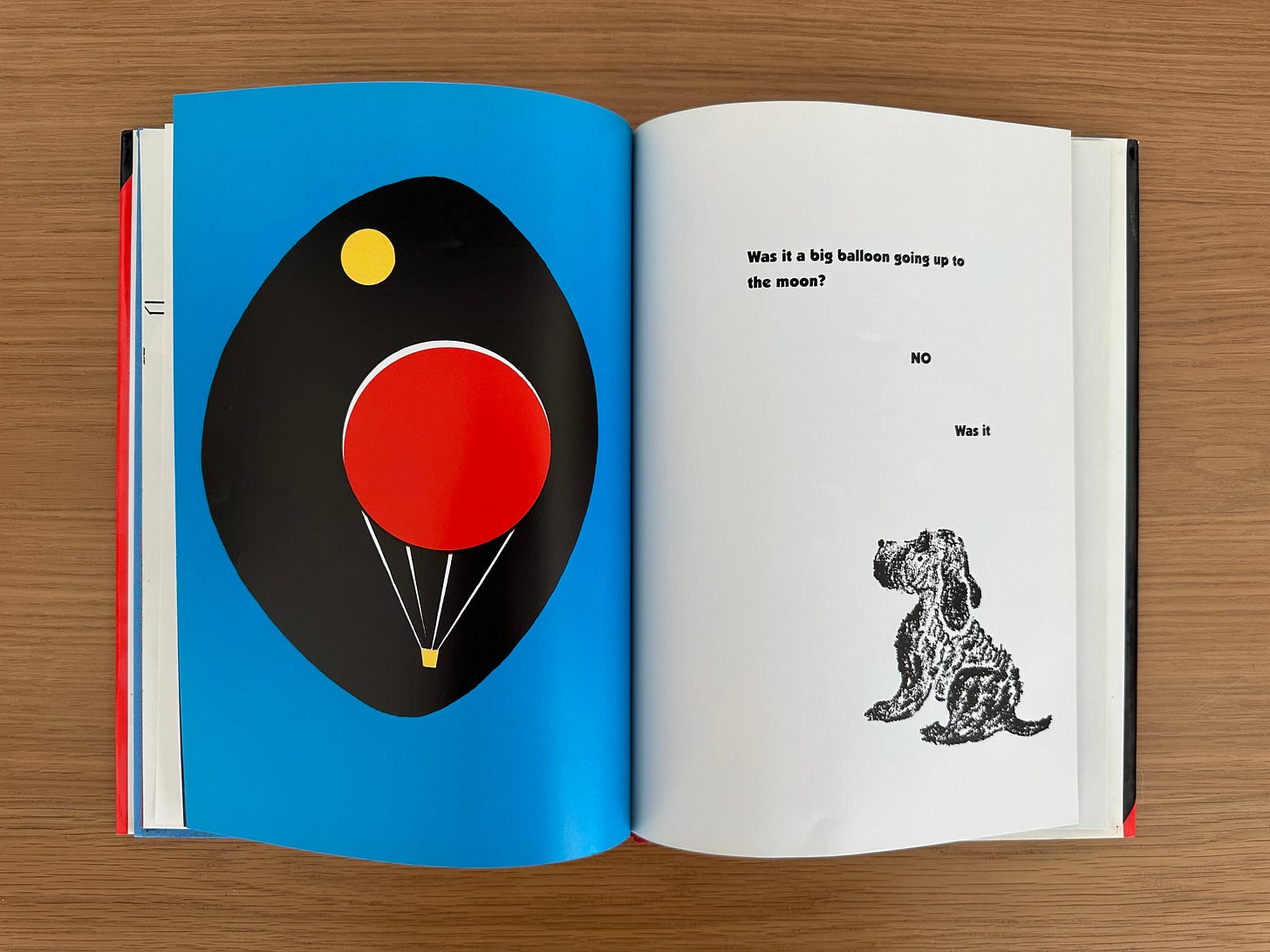

One of my favorites, The Winter Noisy Book (1947), illustrated by Charles G. Shaw, is a shining example of text and image working together to evoke a brisk winter mood. Like Weisgard and Hurd, Shaw used primary colors and bold graphics alongside stark pages in black and white. The effect is alarming, like witnessing the first sign of spring after a long, snowy winter. But it also represents a blank space for children to fill with their imaginations. When Muffin (and the child) question, “A little noise, soft as the sound of people breathing. Soft, soft, soft in the growing darkness,” the spread is almost entirely black, but when you turn the page, there’s a giant red balloon floating up toward the yellow moon in a bold blue sky. Some pictures resemble real life, but others are wildly abstract, like an elusive vision you’d see in a dream. Brown’s text is equally dazzling. There are thuds and scrunches, b-r-r-r-r-r-r-s and sneezes, clicks and crackles; someone blows his nose, someone was eating celery—but what was that soft, little noise?

“Was it a happy elephant snoozing in a hammock? No.”

“Was it someone telling a secret? No.”

“What do you think it was?”

“It was the snow falling out of the sky, of course.”

As with any exercise, there should be moments of rest. In The Summer Noisy Book—one of the more poetic books in the series—there are stretches of slow, sensually stimulating text that allow for greater contemplation.

“He leaned way out to listen. Cowbells on cows at a crossing. The ringing of cowbells. He smelled cows.

And then he saw them

all over the grassy meadows. Cowbells.

And then it was night.

Deep in the country as the moon shone down and the stars pricked the dark night sky, among the dry sounds of summer and the rattle of bugs, Muffin heardpeep peep

Jug a rum

Jug a rum

Jug a rum.What was that?”

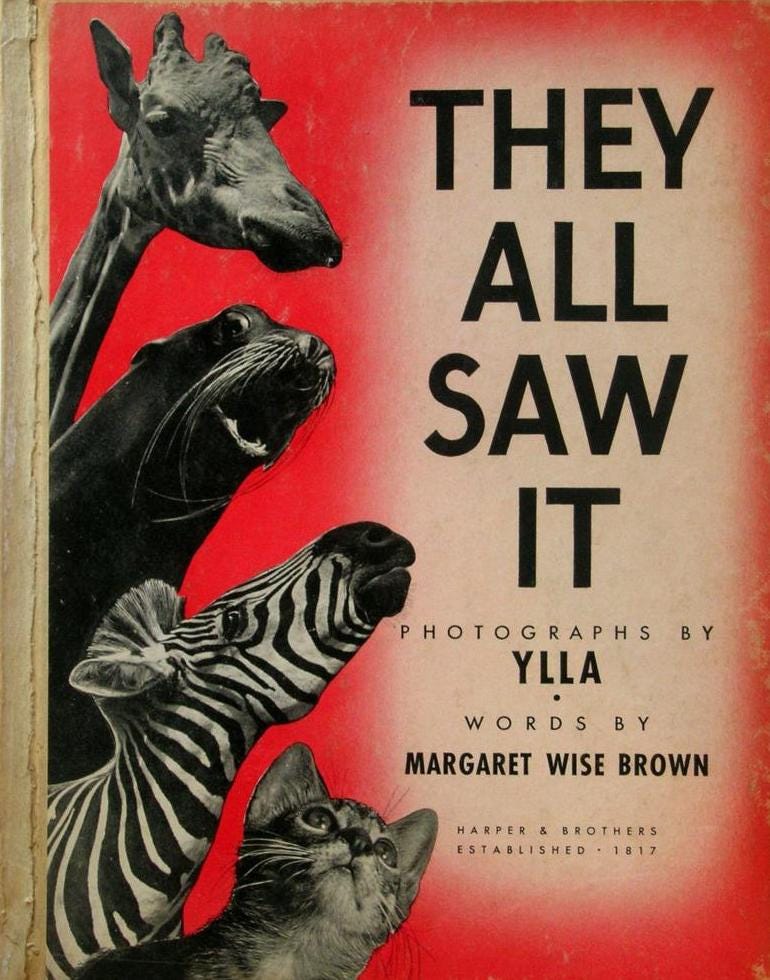

Brown didn’t only focus on the sense of sound. In They All Saw It (1944), she tells the story of one magnificent sight! It’s a fun guessing game like the books in the Noisy Book series, but this time with incredible black-and-white photographs. Brown’s editor at Harper & Row (the iconic Ursula Nordstrom) thought the wildlife photographer Ylla’s pictures were perfect for a story, but she needed an unusual writer to make it work. In the hands of a lesser writer, the book would likely have been a boring story of adorable animals, but Brown created something entirely unexpected and nonsensical. With each page turn, an animal reacts differently to having seen ‘It’ without revealing what ‘It’ is: the rooster rolled his yellow eye; the little cat jumped in the air; the hippopotamus bellowed—but they all saw it (except for the polar bear, he was asleep)! Brown eventually reveals the answer, but it’s not what you’d expect. For adults reading with children, it’s delightful to play along. We grown-ups often forget how to articulate our wild imaginings, but listening to children brings those imaginings to life—suddenly, we can hear, taste, and smell them.

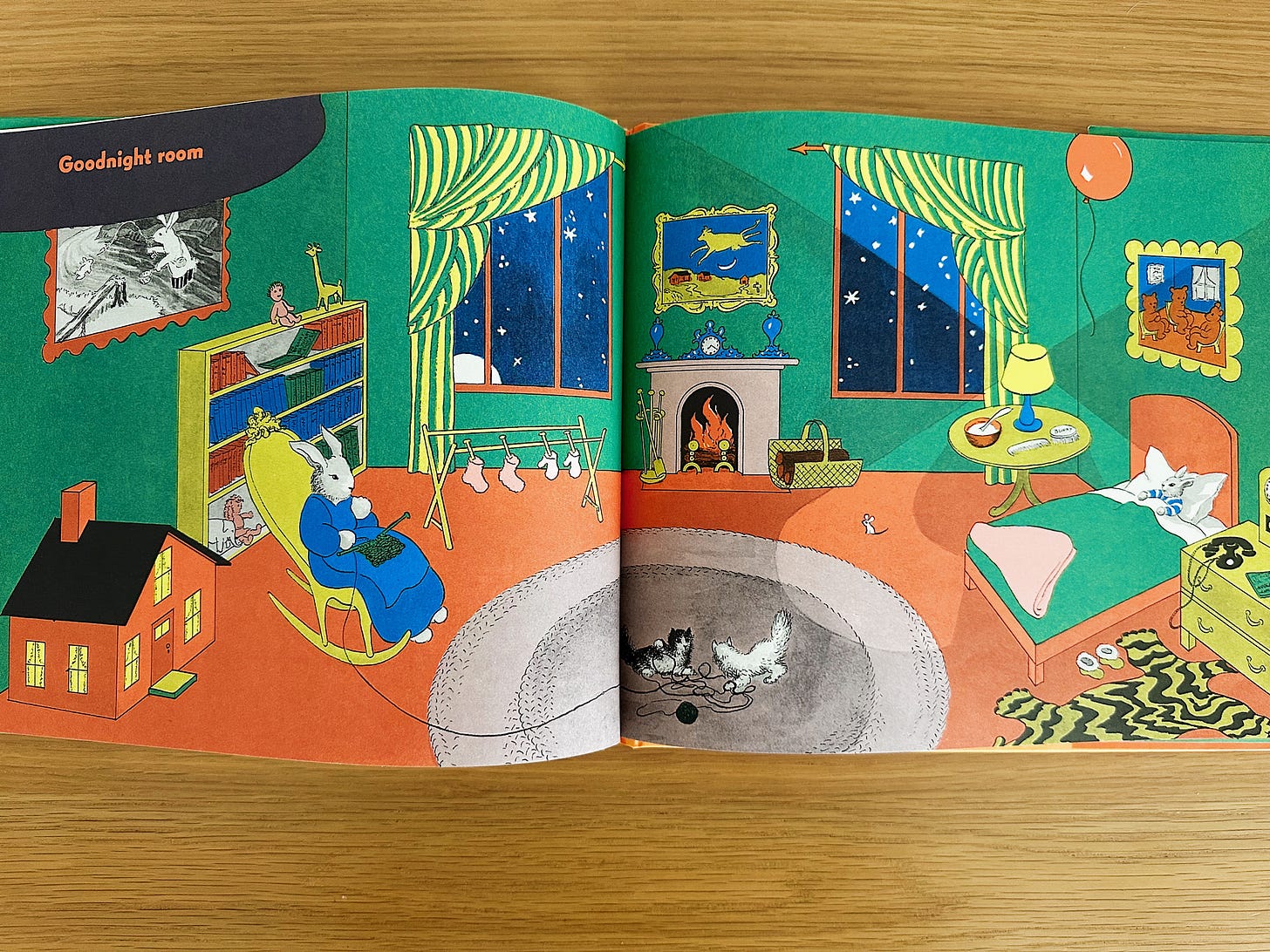

If paying attention is a skill of the senses, Brown’s most famous book, Goodnight Moon, illustrated by Clement Hurd, tests them all. It’s a kaleidoscopic shifting into silence—a silence that slips between the cracks of presence and absence, night and day, awake and asleep—beyond the boundaries of time and space.

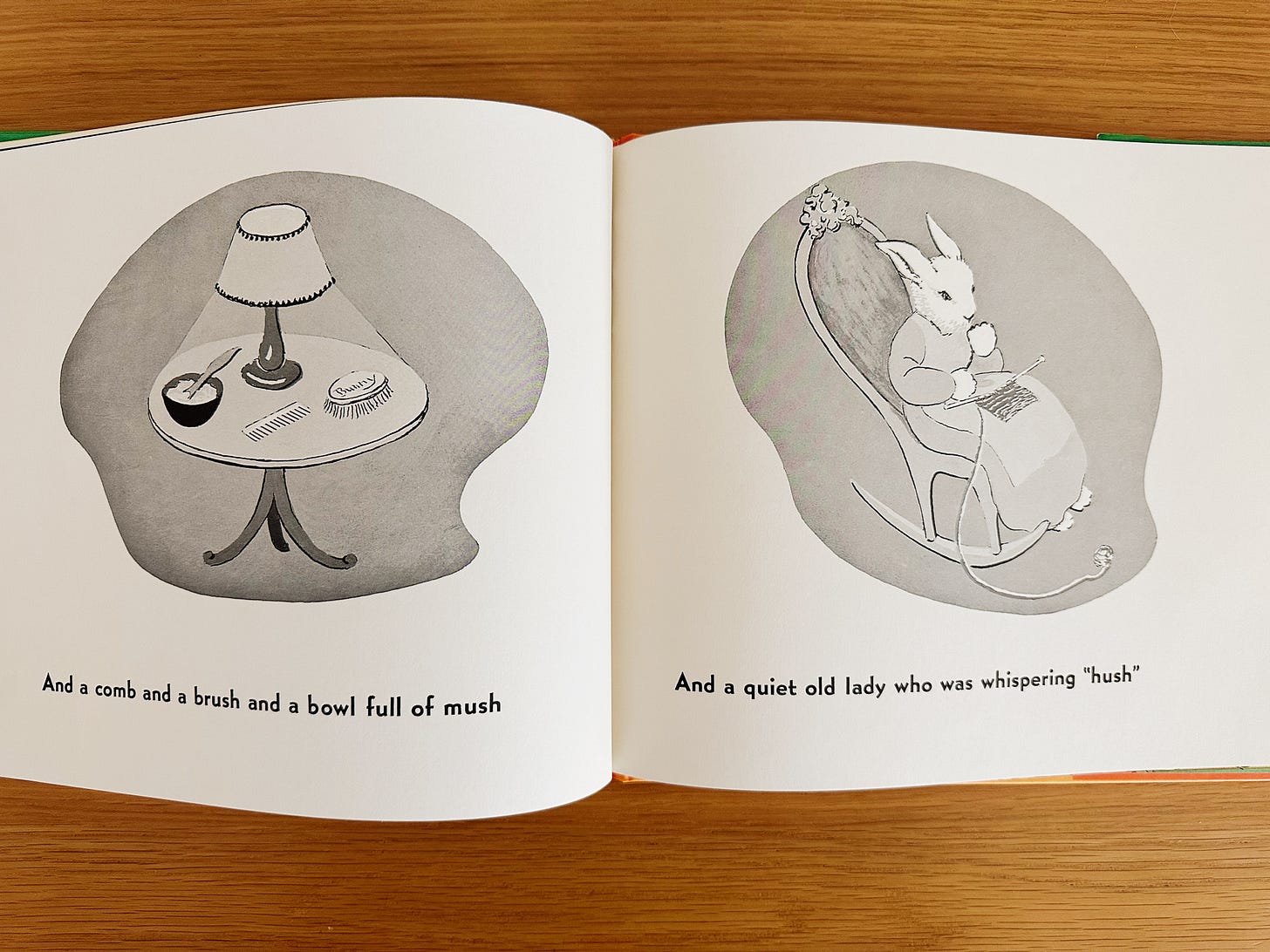

On the surface, it’s a sweet story of a bunny getting ready for bed, saying goodnight to a list of things in his bedroom: two little kittens, a pair of mittens, a little toy house, and a young mouse, and a comb and a brush and a bowl full of mush. As the bunny drifts into sleep, darkness falls, a fire’s aglow, the full moon and sparkling stars illuminate the windows, and the little old lady whispers, “hush.” The musical rhythm of Brown’s text has a hypnotic, incantatory effect. It’s tender and poetically soft, the quintessential bedtime story. Perhaps this is why it’s sold nearly 50 million copies since it was published in 1947 and has become the go-to gift at every baby shower.

While Goodnight Moon can be comforting, it can also be deeply unsettling. The ingenious use of text and image emulates the strange and sometimes scary feeling of drifting in and out of consciousness at bedtime—the hazy, liminal space between awake and asleep. The sense of sight gets foggy; it flickers with hallucinatory visions; things appear, disappear, and reappear again. Other senses are heightened right before they, too, slip away into dreamland.

Children are left spellbound. They hear the clock ticking and the lady whispering; they smell the bowl of mush on the bedside table; they can touch and feel the everyday objects that comfort them—they are immersed in the Here and Now of their home surroundings. And most notably, they have a sense of place and security in the great green room. But not everything is safe and familiar. There’s also the feeling of death—a mysterious void of nothingness that exists in the vast darkness—just beyond the shelter of the great green room. With a sense of humor, children acknowledge the abyss with “Goodnight nobody” and “Goodnight air.” Then, they surrender themselves to nothingness with “Goodnight noises everywhere.” It’s a beautiful moment that gives children permission to be afraid while reassuring them that everything will be okay.

Like Brown’s childhood writings, Goodnight Moon is a brilliant textual collage—a rich tapestry of real-life observations interweaved with poetic imaginings, a Here and Now fairy tale. The book creates space for uncertainty, mystery, and doubt without facts or answers. It encourages children to use the full force of their unyielding imaginations by asking them to not only fill in a blank but to jump into it.

These days, it’s increasingly difficult to pay attention. We’re living in an age of distraction. We’re bombarded with information and grossly overstimulated. Books, television shows, and films are getting shorter, louder, and flashier. There’s no time for quiet. There’s no time for thinking. But reading Margaret Wise Brown helps. Her poetry is a way for us to pay attention to the things we tend not to pay attention to: the belly of a bumble bee, the sound of a train roaring across a darkening sky, the salty taste of air by the sea, and once we notice them we realize, it’s the small moments that make up a big, beautiful life.

Sound Bite

Brown once said, “In the back of my head, I keep busy; in the front of my head, I am slow and stupid.” This is precisely how I felt while writing this piece. I was constantly thinking, reading, looking, listening, feeling, absorbing, synthesizing—trying to make sense of abstract connections—but writing those connections as words on a page felt slow, stupid, and sometimes horribly frustrating.

Now that I’m done (which feels like the wrong word to use), I realize it was hard because much of what I was trying to write about existed as sensations in my body, not as thoughts in my brain. I was having this sensuous, aesthetic experience while at the same time trying to write concretely about it. It didn’t work.

With some time and distance, I was able to piece together my thoughts and feelings. Although I still believe Brown’s books are books you inhabit—you live inside them, you feel them—to understand their brilliance is difficult and probably isn’t necessary. But I love digging deep into craft and process.

If you’re not into reading a lengthy newsletter, you can listen to me briefly talk through these ideas here:

Support Moonbow

Writing these articles is tough and rewarding work. If my time, ideas, and research are valuable to you, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Can I afford to continue Moonbow? It’s a serious question that’s becoming more pressing with time. I don’t want to offer freebies or bonus content to entice you into becoming a paid subscriber. I want to deliver the best, richest newsletters I can. I want to be excited about what I write. I want you to be excited. If you love reading Moonbow every month, becoming a paid subscriber is the best way to show your support. It’s $5 monthly or $50 annually—or you can become a founding member—and pay any amount you want. If that’s not possible, sharing Moonbow and liking and commenting on articles are other great options.

With gratitude,

Taylor

A big shoutout to these references and resources:

Writing for Five-Year-Olds by Margaret Wise Brown (1939)

Margaret Wise Brown: “Laureate of the Nursery” by Louise Seaman Bechtel for The Horn Book (1958)

Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon by Leonard S. Marcus (1992)

In The Great Green Room: The Brilliant and Bold Life of Margaret Wise Brown by Amy Gary (2018)

Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Books as an Adult by Bruce Handy (2017)

Ten Windows: How Great Poetry Transforms the World by Jane Hirshfield (2015)

Shifting The Silence by Etel Adnan (2020)

Ten Windows: How Great Poetry Transforms the World (by Jane Hirshfield (2015). Chapter 7 (window 7)—“Poetry and the Constellation of Surprise.”

Ten Windows: How Great Poetry Transforms the World by Jane Hirshfield (2015).

Margaret Wise Brown “Laureate of the Nursery,” The Horn Book, Louise Seaman Bechtel (1958)

Thank you for forcing me to slow down and linger with the genius of MWB; as a nanny I’ve read Goodnight Moon to many a young child over the years, and it’s one that you have to read multiple times (which thankfully young children demand!) in order to appreciate its quiet rhythm. In my used-children’s-book-shopping over the years I have come across and been curious about her other books, but haven’t taken the time to read them; now I will seek them out.

One difference of opinion I have is on the line “Goodnight nobody”; I have always read it as playful rather than eerie, as a wink to the stalling ways of a child who is saying goodnight to as many things as possible in order to delay bedtime; I also find the word “mush” humorous, though I don’t know if it’s a shift in language over time that makes it sound so silly, or if it was always meant that way.

Thank you for your wonderful writing, and for bringing more appreciation to the overlooked world of artistry in children’s literature 🥰

I LOVED IT SO MUCH! Taylor, you did such a good job capturing the essence of how it feels to inhabit her books. Not any easy feat. You are amazing ❤️