A Shock of Delight

Three poetic picture books with a Woolfian spirit

“And so I go on to suppose that the shock-receiving capacity is what makes me a writer,” Virginia Woolf observed in her posthumously published collection of autobiographical writings, Moments of Being (1976). Woolf was fascinated with the instability of the mind, the way it flickers, catching some things and ignoring others. She describes these momentary flashes of awareness as a shock, a feeling of intense energy and curious focus, a vivid fleeting moment of consciousness. In these sudden “moments of being,” as Woolf referred to them, we catch a glimpse of our connection to the larger world, a moment that would otherwise be hidden among the mundanity of our daily lives, the “moment of non-being.”

Long before reading Woolf’s writings, I was struck by the idea of “moments of being,” although I didn’t have a name for it, so I gave it one: “flashes of delight.” I experienced startling moments of full consciousness as a child, and like Woolf, I believe they’re the reason I’m drawn to writing. Sometimes, they were pleasurable, but other times, they were dreadful. Like the time I sat in a dark movie theater and suddenly thought, for the first time, of my inevitable death. I remember a hot flash flooding my body, the tips of my fingers tingling, and my heartbeat throbbing loudly in my ears. It’s a feeling that returns to me occasionally, almost always at the movies. Experiencing an existential panic attack as a child is an extreme example of an intense conscious experience, but even ordinary moments can produce exquisite feelings of awareness.

Growing up, I was drawn to light and shadows (I still am)—sunlight’s warm kiss on my skin, a comforting moonlit window in the dark, the sparkling ocean at sunset—it’s probably why all of my brands have been named after reflections of light (“Moonbow” “Glitter Guide”). In hindsight, “Glitter Guide” wasn’t the best name for a lifestyle publication. At the time, I liked glitter (a lot!), and I liked alliteration (I still do). Still, the name didn’t reflect our intentions; however, our tagline, “flashes of delight,” did. It was a play on the definition of glitter, “flashes of light,” but with a twist: a reminder to pay attention to those fleeting moments of being.

Despite my ongoing attempts to pay close attention, it’s harder than it used to be. Life is busy; more routine. Feelings of rapture are harder to come by. The world no longer feels vast and mysterious, or maybe I just have less patience for mystery. The moments of non-being seem to take over, and I have to fight to maintain my shock-receiving capacity. This adult-onset numbness is a big reason I’m attracted to children’s books. They are filled with secret doors and curious questions. To children, something strange and wonderful happens every day. The same is true for adults; we just have to pay better attention.

Children have heightened instincts and attachments. Their keen focus allows them to see details with extreme distinctness. In her memoir, Woolf describes a striking moment in her childhood when she noticed a flower in a garden bed, and it suddenly became clear to her, “That is the whole.…the flower itself was a part of the earth; that a ring enclosed what was the flower; and that was the real flower; part earth; part flower.” Suddenly, she was fully conscious of the pattern hidden behind “the cotton wool of daily life” and her connection to it.

Although Woolf never concretely defines what “moments of being” are, she beautifully describes what these moments illuminate to her:

“Behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern; that we—I mean all human beings—are connected with this; that the whole world is a work of art; that we are parts of the work of art. Hamlet or a Beethoven quartet is the truth about the vast mass that we call the world. But there is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and empathetically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself. And I see this when I have a shock.”

When I experience a shock, it feels as if every molecule in my body is vibrating at a higher frequency; I’m more attuned, more porous—and for that brief moment, I’m intensely aware of being alive. They happen unexpectedly, often from ordinary events, yet reveal something special about my identity. The sudden flash focuses my attention simultaneously in two directions: toward the object and toward myself. Even if the moment is lost soon after, buried under the routine of daily life, it reemerges later, usually in my writing. Writing conjures it back into existence and helps me make sense of it.

“Art is the realization of a complex emotion.”

— Jeanette Winterson, Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery (1995)

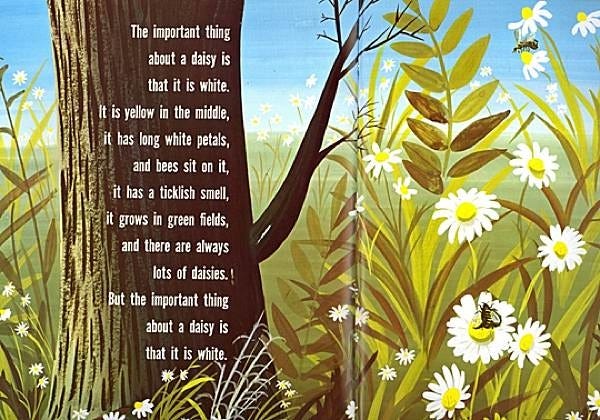

Reading also energizes these emotions, and because children are highly sensitive to beauty, children’s books best evoke this visceral experience. Margaret Wise Brown wrote prolifically about children’s rapturous delight in small things. The Important Book (1949), illustrated by Leonard Weisgard, takes simple everyday things a child may encounter—an apple, a flower, grass, shoes, the sky—and describes what is important about them. It’s a playful, poetic game that encourages children to decide what is essential and question how those decisions define them as individuals. Even though Brown gives more obvious answers, like “the important thing about grass is that it is green,” she also includes unique perspectives, like how the grass is “tender” or the important thing about a daisy is “it has a ticklish smell.” She knew that children see everyday things in extraordinary ways.

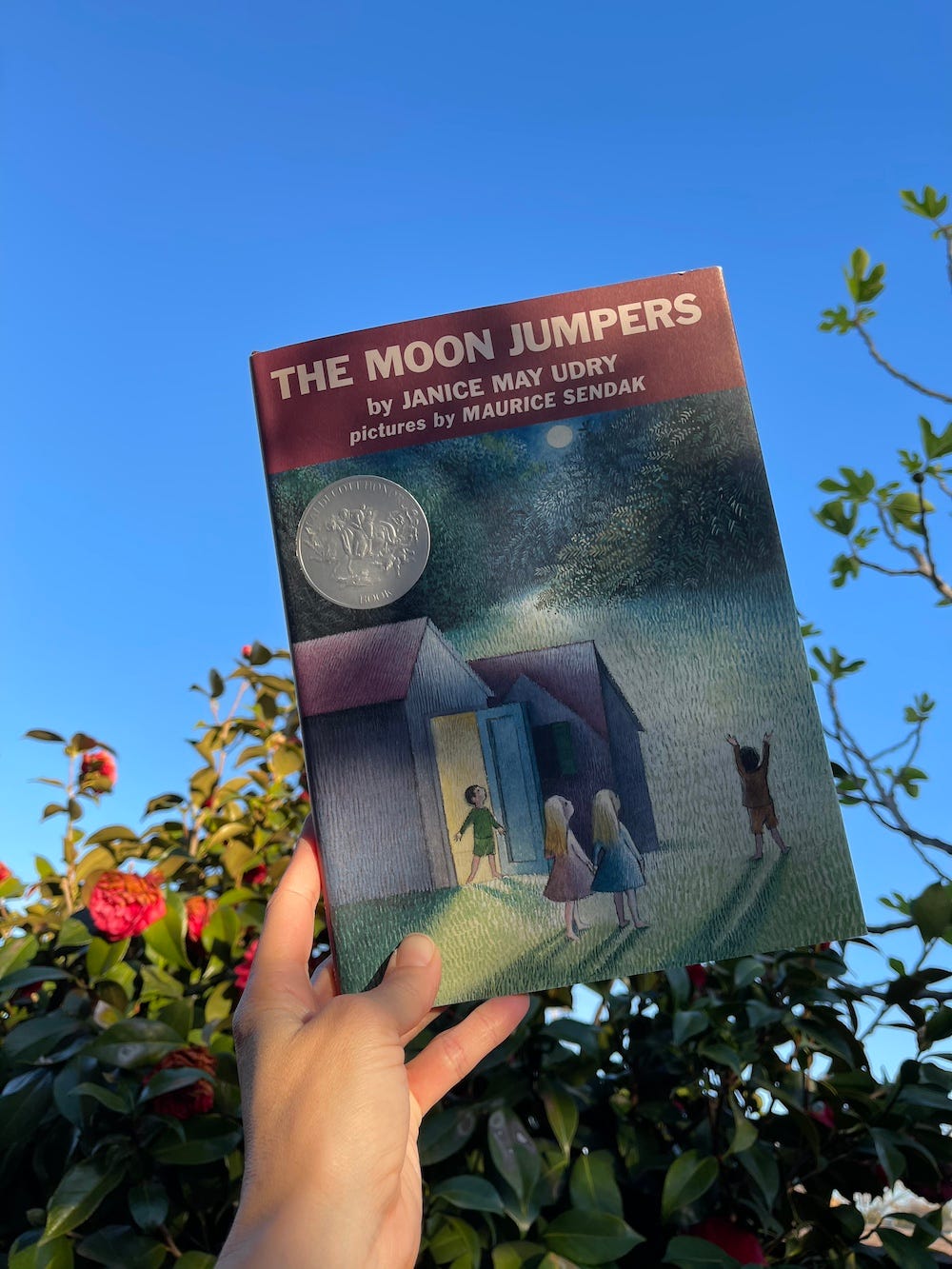

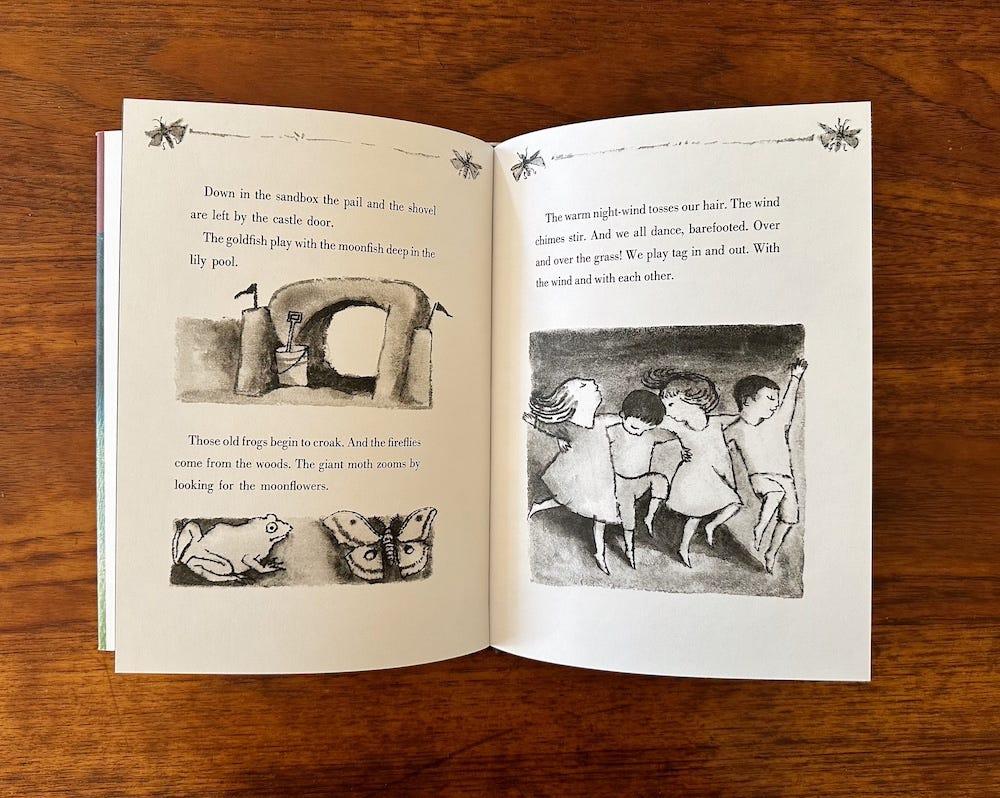

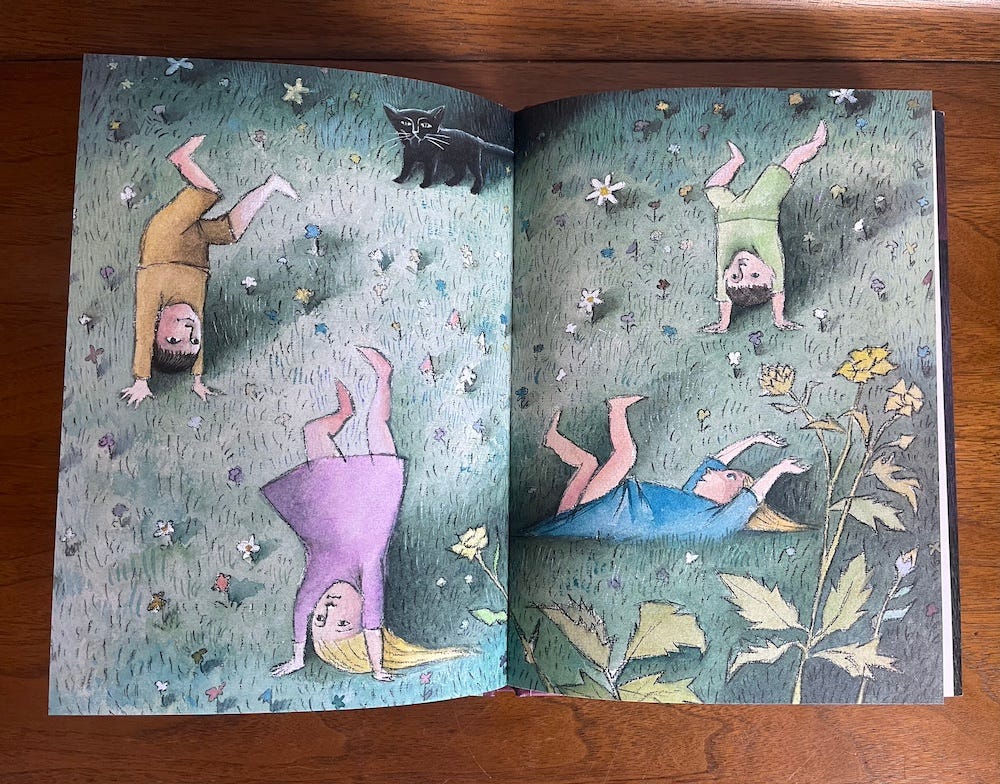

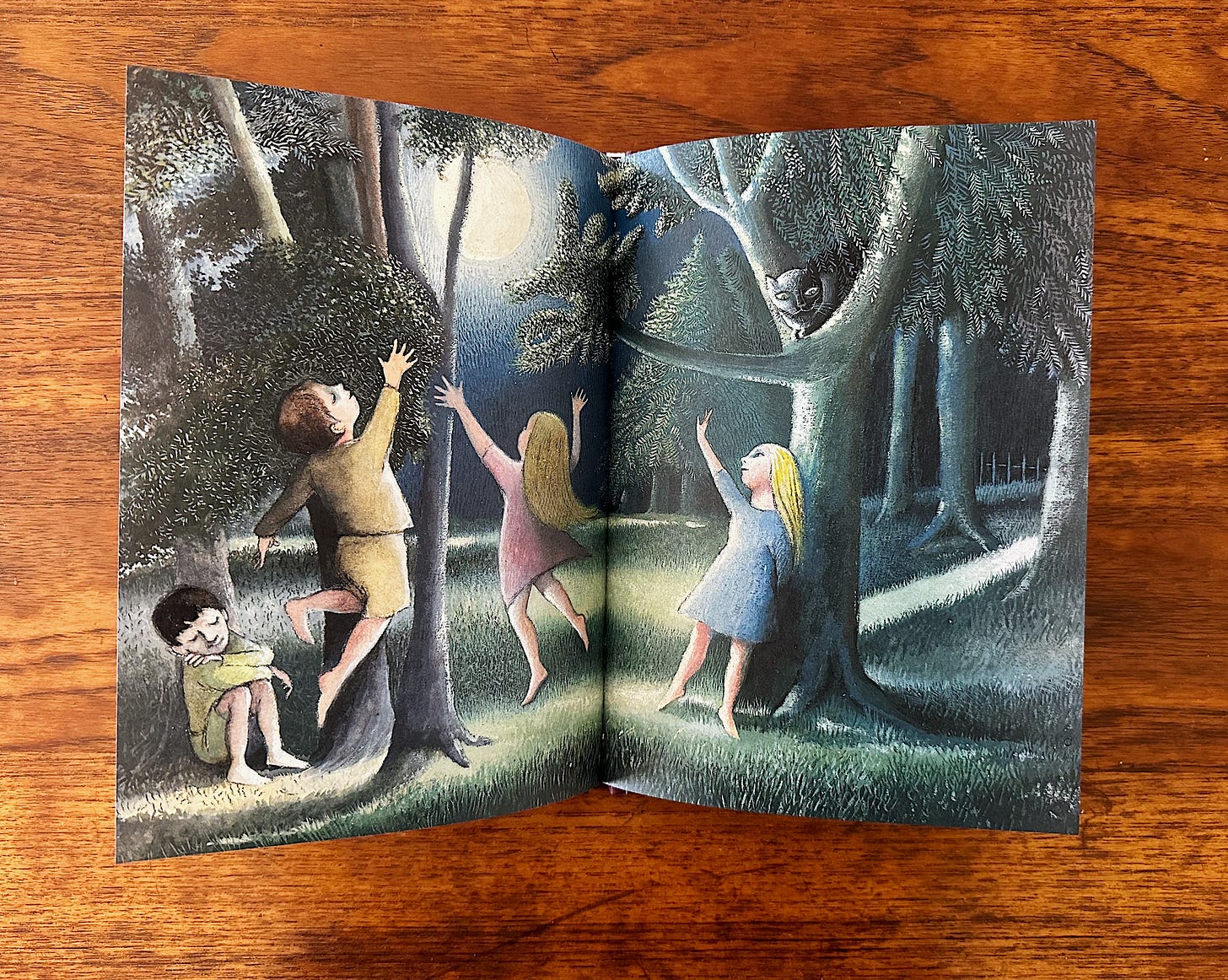

The Moon Jumpers (1959), written by Janice May Udry and illustrated by Maurice Sendak, is an enchanting story of childhood wonder—an enduring but trite theme in children’s books; however, this book gets it right. It’s a hot summer night drenched in dreamy moonlight. The children are barefoot and feral, frolicking, dancing, and somersaulting through “the cool dark grass” and up the “big tired trees.” A giant moth “zooms by looking for the moonflowers,” and the “warm night-wind” tosses the children’s hair. They play tag, sing songs, tell ghost stories, and jump, jump, jump at the moon. A large ominous shadow lurches toward them on the grass; it’s a GIANT! But it’s just Father lighting his pipe as he takes a moonlit stroll to check on his roses. Mother calls the children inside. They protest, “We’re not children, we’re the Moon Jumpers!” But soon, they surrender and head to bed, where they sleepily slip under their cool, soft sheets as the moon sails on up the sky.

Udry’s rhythmic text is somehow simultaneously soft and effervescent, juxtaposing the evening’s warm, gentle breeze with the children’s lively, bubbling excitement. It captures a fleeting childhood moment that adults look back on fondly. You could argue that this book is aimed at nostalgic adult readers, but there’s plenty for children to luxuriate in, especially Sendak’s Caldecott Honor award-winning illustrations, which, similar to Udry’s text, effortlessly transition between black-and-white and rich, bold color. They feel alive, full of energy and spirit. Opening the book, you feel as if you’ve snuck out at night into the glowing garden with the mysterious black cat and bellowing bullfrogs. Inhabiting this book is a pulsating bodily delight.

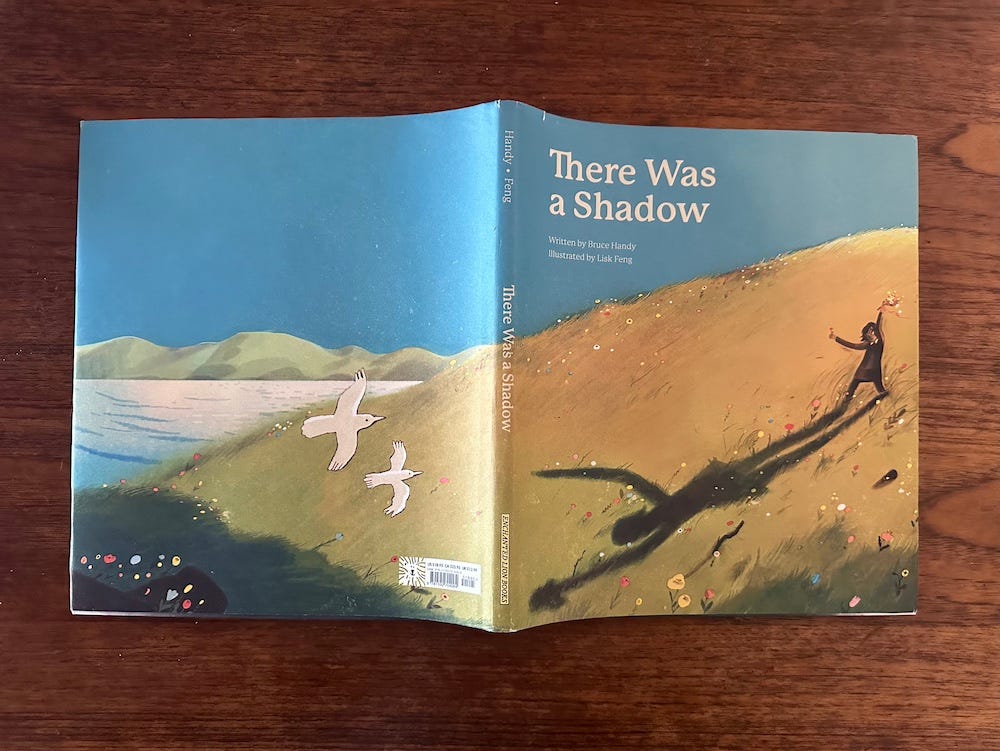

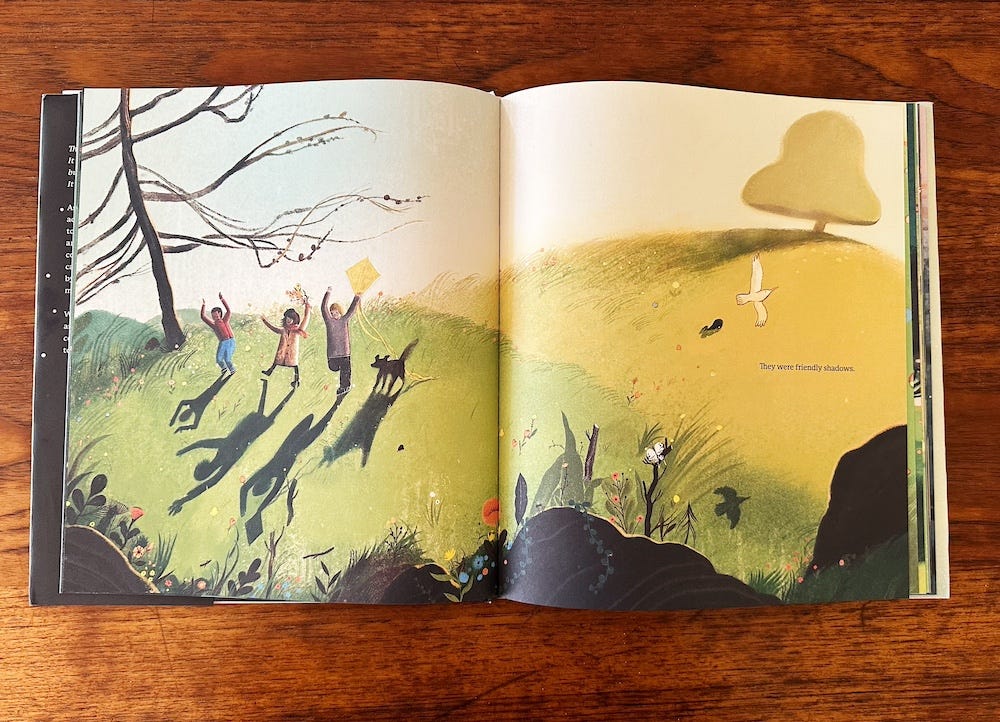

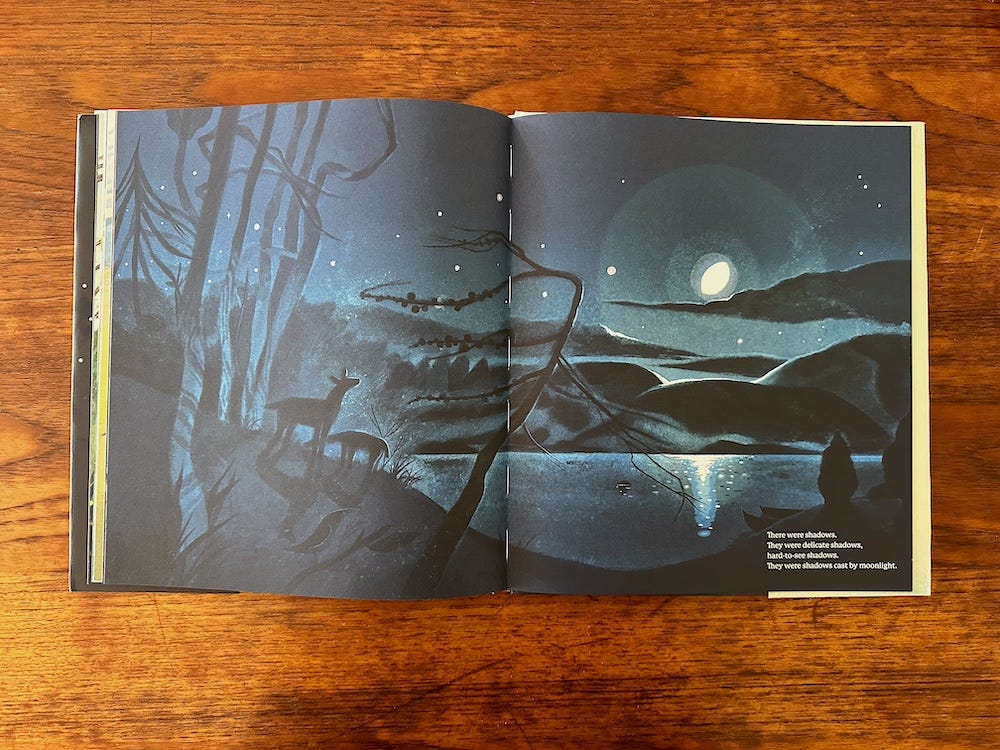

In the new picture book, There Was a Shadow (2024), there are “no moonbows, but moonlight for sure,” as its author, Bruce Handy, sweetly inscribed on the title page of my copy. The book is a poetic catalog of light and shadow in the natural world and within ourselves. From the early morning sunrise to a pale moonlit evening, the story follows a young girl and her friends as they explore the outdoors and encounter many kinds of shadows. There are the obvious—tall, skinny, soft, short, hard, faint—but also the playfully unexpected, like one of my favorites, “a look-closely shadow.” Handy avoids writing anything eerie or scary. Instead, he tenderly describes the way light and shadow flicker in our minds and hearts. His sensitive, lyrical text acknowledges the complex emotional contrasts of being a child (of being human). As Woolf wrote in To the Lighthouse, “A light here required a shadow there.”

Lisk Feng’s illustrations are equally luminous, if not more so. They move rhythmically, step by step with the girl, as the sun moves across the sky. We turn from page to page; the hours pass; light fades in and out, expanding and contracting, dancing and dazzling. Color and composition play with the changing dimensions of light and shadow, creating a vivid psychological portrait.

Pouring over the pictures, I’m inevitably struck by a shock: On an ordinary day, in the observable world, inside a bug’s shadow or a shimmer of sunlight on a cheek, the spectacular truth of existence is briefly revealed before it quickly fades back into the shadows.

If you liked this article, you may also like:

Paying subscribers get total access to everything Moonbow publishes. That means:

Complete access to Moonbow’s literary criticism, reviews, and recommendations.

Exclusive access to book guides, video meet-ups, online courses, and merchandise (coming soon!).

The full archive of Moonbow’s articles, dating back to March 2022.

But more importantly, becoming a paid subscriber allows Moonbow to stick around! While it’s fun, it’s definitely not easy to dedicate hours to researching, writing, editing, and marketing this publication. So, if you enjoy Moonbow and want to support it, becoming a paid subscriber is the best way.

Moonbow has many amazing opportunities to grow and become a more robust platform for children’s books. By becoming a paid supporter, you’re helping make those dreams a reality.

Lovely! I requested all 3 of these at the library to enjoy. One picture book I think would fit well with this list is Reeve Lindbergh’s The Midnight Farm, with illustrations by Susan Jeffers.

Hi Taylor,

Reading this felt like having an echo of a moment of being! Like you, I’ve had those moments, as an adult too, and I never had a name for them. But it’s always felt like Woolf describes it in her quote: where the distinctions we make fade away, and I realize (remember?) that we are the music, the Iris, the seagull, the tree, and each other. (I’d use the word ‘oneness’ but that’s never felt like it describes those experiences.) Its more like reality slots into place, and the world reveals itself. Simple and humbling and profoundly beautiful.

Thanks for introducing me to Woolf btw. I had no idea she’d talked about anything like this. I have a sudden hankering to read everything I can of here now.

P.S. Just discovered your essay via Brad Montague’s Substack. Very glad to have done so :)