The Alchemy of Storytelling: A Mixture of the Deeply Familiar With the Totally Unexpected

Jon Klassen's "The Skull" + a dash of Calvino, a sprinkle of Scieszka, & a hint of Kafka.

Hi Moonbow readers! Today's article is about Jon Klassen's new book The Skull—a fantastic adaptation of a Tyrolean folktale—but it's also about storytelling. What makes a good story? What are the mysterious elements that make a story magic? Why do folktales have such enduring appeal? These are some of the questions I asked myself after reading The Skull. I sat with them for weeks, not sure of my way in. It wasn't until I revisited Italo Calvino's Italian Folktales that I realized the word "in" was the key. What great stories do well is invite readers (or listeners) in—not just escapism—but as co-creators of the story. Folktales especially—with their liminal space and ambiguous endings, allow readers to fill in the blanks with meaning. Perhaps this is why our favorite stories feel more like memories than books. They become a part of us.

“Those who know how rare it is in popular (and non popular) poetry to fashion a dream without resorting to escapism, will appreciate these instances of self-awareness that does not deny the invention of a destiny, or the force of reality which bursts forth into fantasy. Folklore could teach us no better lesson, poetic or moral.” —Italo Calvino

“The tale is not beautiful if nothing is added to it.” —Nerruci

Ursula K. Le Guin’s review of Italo Calvino’s Italian Folktales (English edition translated by George Martin, 1980) warns that moralizing folktales is risky business. Assigning a moral or meaning to these stories is like “stating the meaning of a fish, the uses of a cat. The thing you are talking about is alive. It changes and is never quite what you thought it was, or ought to be.”1 She says, “One of the innumerable delights of Italian Folktales is its mixture of the deeply familiar with the totally unexpected.” We recognize human anxieties and desires even when they’re happening in wildly unfamiliar worlds. The tales illuminate “the force of reality which bursts forth into fantasy,”2 as Calvino states. Yet, many folktales and fairy tales do have an overt message they’re trying to communicate. This isn’t always a bad thing. There’s comfort in believing these stories are metaphors for growth—and they can be—but only when there’s space for the audience to decide the value for themselves. Part of the pleasure of reading Calvino’s folktales, or any of his stories, is not having a lesson jammed into your brain. He invites readers on a delightfully disorienting journey, but it’s never pure escapism. The folktales offer us ways of seeing our dream destinies, but these destinies come at a cost; we must slay the dragon, trick an ogre, help the poor, defeat the witch, and marry a frog first.

Franz Kafka was one of Calvino’s literary heroes. His influence is sprinkled throughout Calvino’s short stories and folktale retellings. Even when the stories are absurd, which they often are, they’re written in a laconic, concise style. Calvino once described Kafka’s writing as "using a language so transparent that it reaches a hallucinatory level.”3 And it’s this strange alchemy of elements that enchants so many readers, especially children. Children don’t respond to moralistic lessons; they respond, almost involuntarily, to feelings, sights, sounds, colors, ideas, humor—and then they absorb, morph, and distort them, creating something fresh and new. They are invited into the story, but more than that, they’re granted permission to rewrite it. This is what some children’s authors get wrong. They think they need to cover everything. They lack confidence, not only in themselves but in their readers.

Contrary to what many may believe, children are more adept at interpreting ambiguous stories than adults. Have you noticed the most popular children’s books are often the strangest ones? Books like Goodnight Moon (1947), Where the Wild Things Are (1963), and The Giving Tree (1964) are dark, weird, and difficult to interpret. They rose to the top of the bestseller list, and have remained there for decades, despite the grumblings and book bannings from confused adults. Why is a tiger skin rug in “the great green room”? Who is that mysterious old lady whispering “hush”? What did Max do to lose his dinner? Why does the tree keep enabling the boy even though he treats her poorly? These stories don’t give us answers; they provoke questions. And children love to ask questions.

If we marketed Calvino’s stories to children better—they’d probably be some of their favorites—the folktales, without question, but even his beguiling collection of cosmic fables, Cosmicomics (1968). Fiercely inventive and playfully imaginative—the twirling, whirling, fragmented stories of Cosmicomics challenge perceptions of time, space, and our purpose in the universe. We’re left floating in cosmic nebulae, among dusty clouds, between the stars, in the galactic possibilities of the imagination. The stretchy dimensions in space—and in stories—encourage stretchy thinking. Perhaps this is why the famous children’s book author and educator Jon Scieszka used to read Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915), the story of a man who turns into a bug, to his 8-year-old students—their elastic minds made them the ideal audience for the unfathomable.

Scieszka, best known for his fractured fairy tales, The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales (1992), grew up fascinated by myths and folklore. Many of Scieszka’s books draw upon the ancient tradition of oral storytelling—a form of narrative “quickness”—a term coined by Calvino, who stressed that a fundamental characteristic of folktales is their “economy of expression” and that “everything mentioned has a necessary function in the plot.”4 Folktales demand inventiveness, a light and playful combination of rhythm, speed, and story. They are best told by alchemists like Scieszka and Calvino, who aren’t afraid to experiment with reactive substances that disrupt the expectations of conventional narratives.

Sometimes, it’s waking up as a bug; other times, it’s meeting a talking skull. That’s what happens to Otilla, the brave protagonist of Jon Klassen’s enchanting new book, The Skull (2023), an adaptation of a Tyrolean folktale.

The book opens with:

“One night, in the middle of the night, while everyone else was asleep, Otilla finally ran away.”

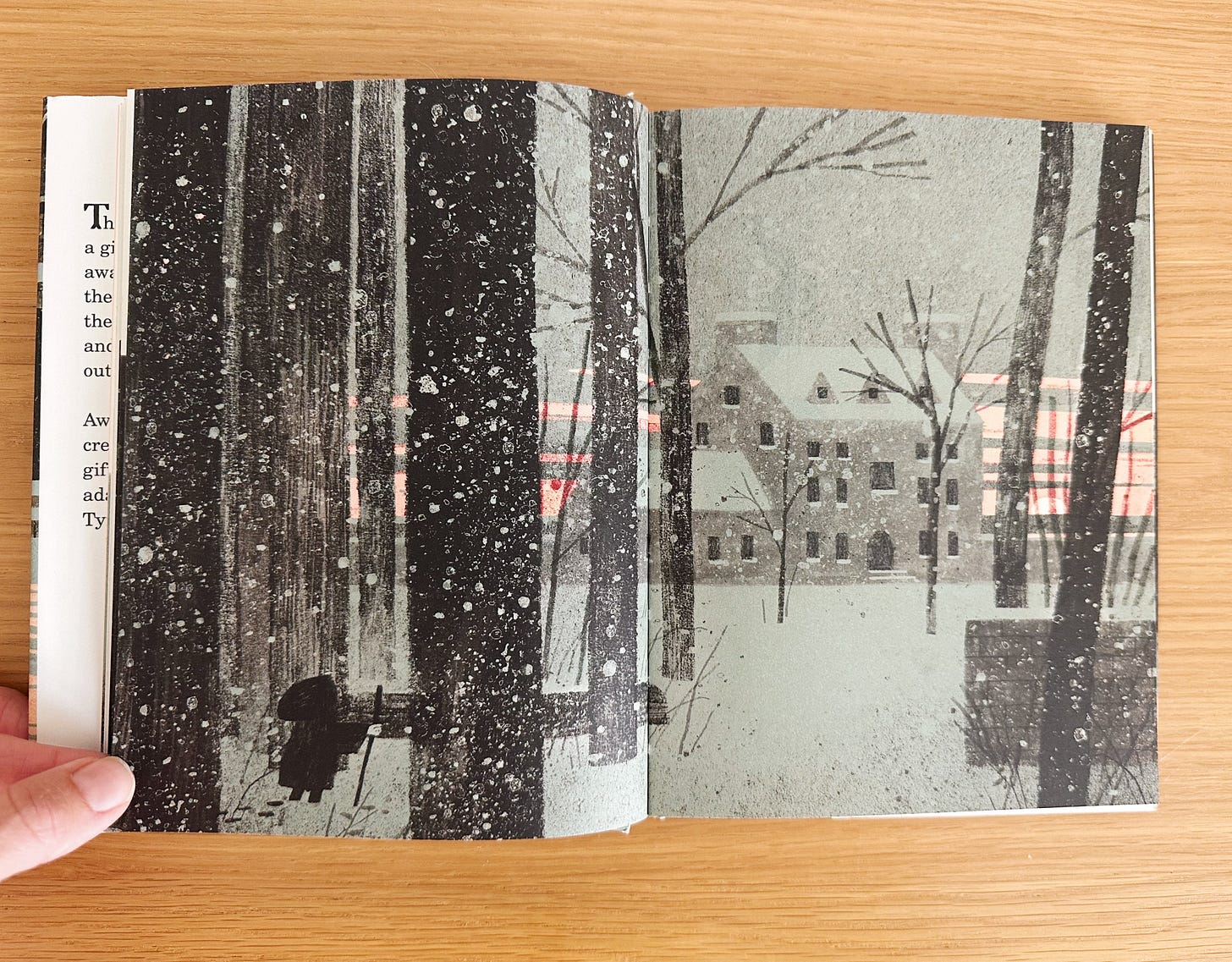

Why did Otilla run away? We never find out. But we can think of reasons, and the word “finally” lets us know she needed to. After hours of running through the cold, dark forest, Otilla finds herself lost with nowhere to go.

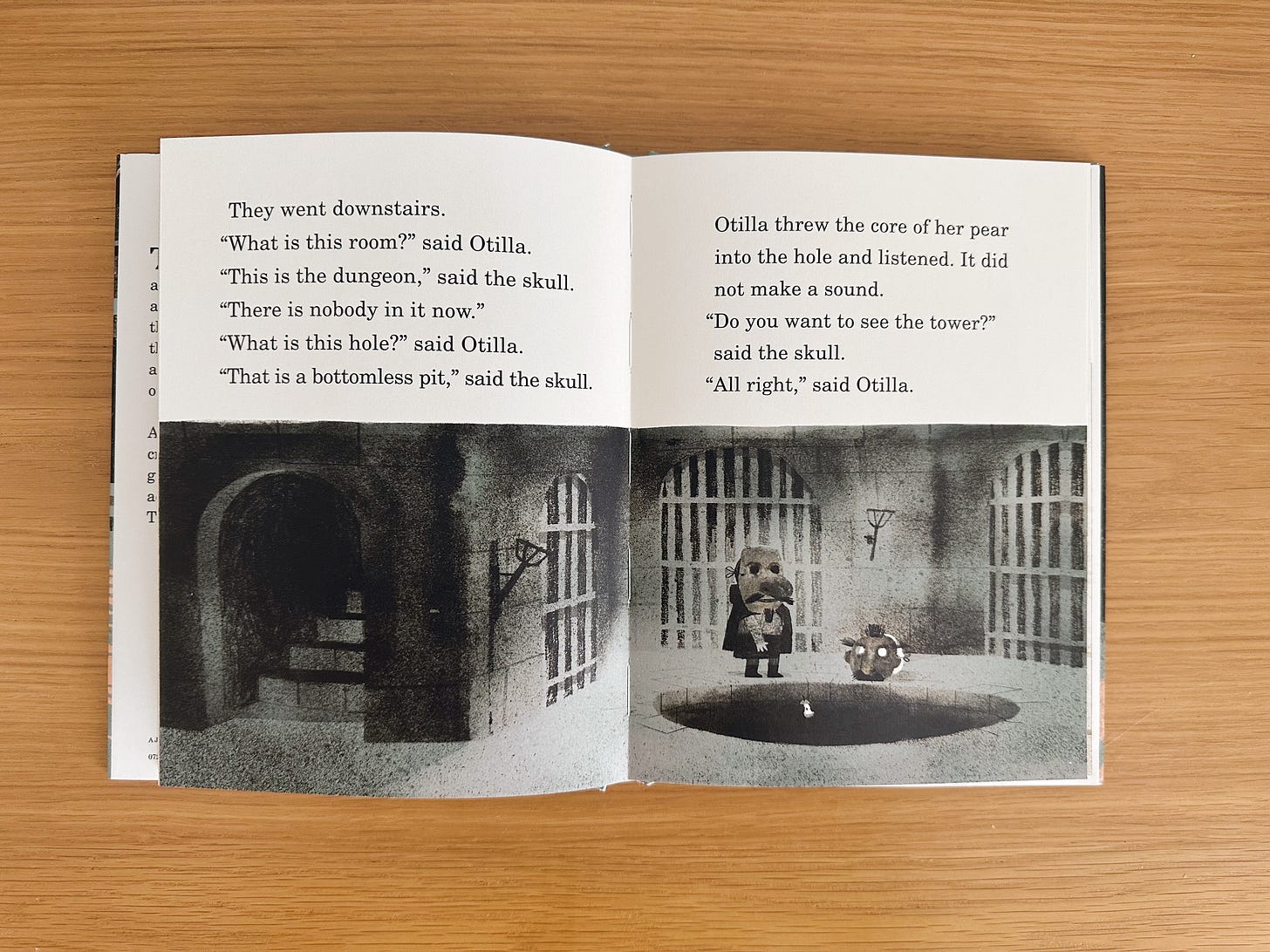

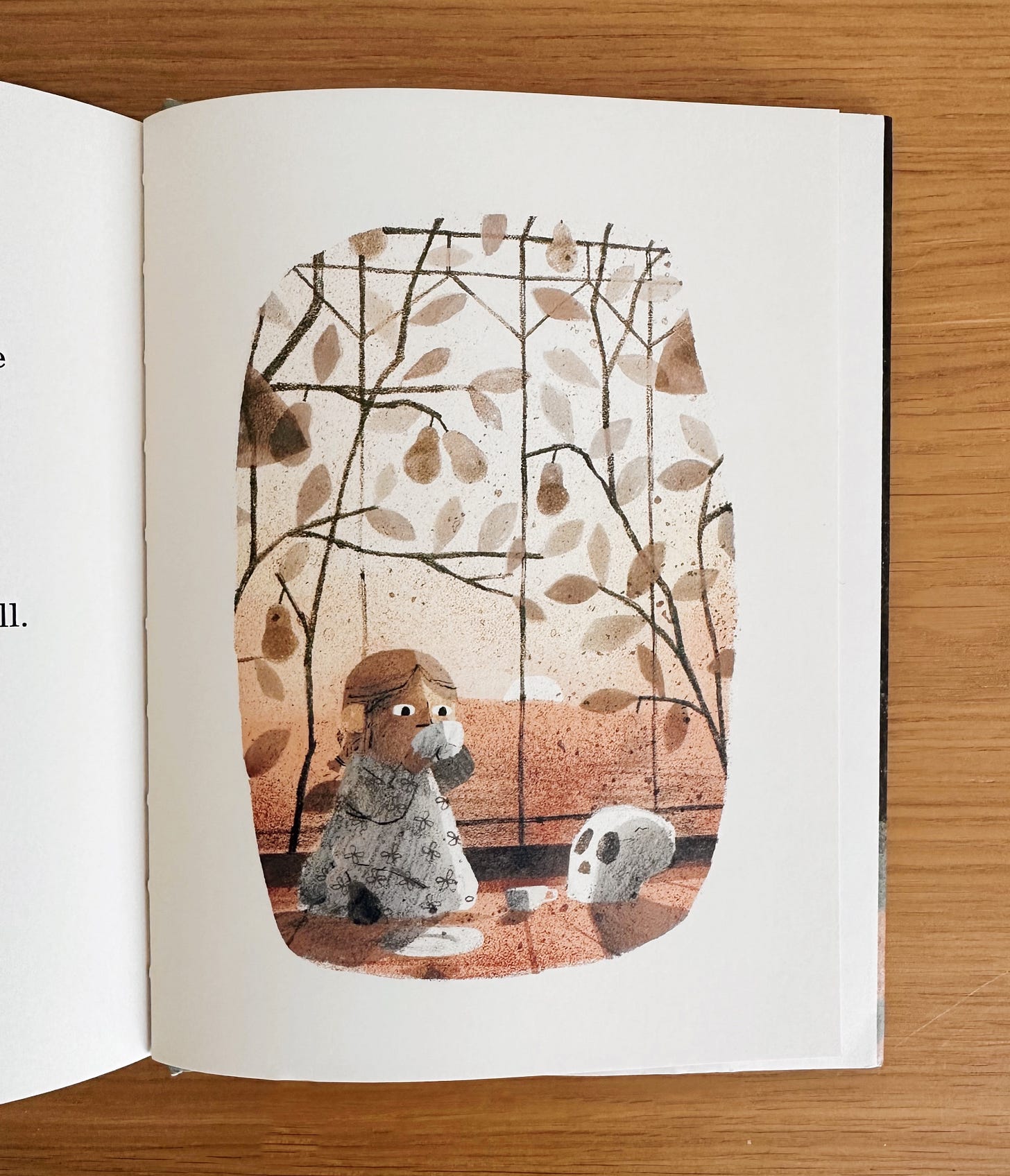

Eventually, a warm, pink sunrise breaks through the bitter darkness, and Otilla finds herself in front of an old, abandoned house where she meets a gentlemanly skull who’s lived there a very long time. They hit it off immediately. The skull takes Otilla on a tour of the grand house: they drink tea by the fire, snack on pears in the garden room, and have an old-fashioned dance in the ballroom. In my favorite page turn in the book, Otilla and the skull enter a room where ancient masks hang on the wall.

“What are the masks for?” said Otilla.

“I used to collect them,” said the skull.

“Can you wear them?” said Otilla.

“They are just for show,” said the skull. “You are not supposed to wear them.”

You turn the page, and they’re wearing them, no explanation. The story continues, and they wear them for a few more pages. A hilarious but silent punchline told only in the picture.

As the day turns to night, the skull invites Otilla to sleep there, but first, she must know that a headless skeleton comes to try and steal the skull away every night. Rather than being terrified, Otilla considers the situation stoically, deciding to stay and help protect the skull. What happens next will delight and possibly disturb but is ultimately satisfying. I’ll keep the details secret except for one big spoiler: she beats the skeleton (pun intended).

Throughout the story, neither the skull nor Otilla probe too deeply into the other’s backstory. From the start, they sense a shared connection over tough, unspoken truths. In some other versions of the tale, there are more explanations, and the ending is different, more tidy. What makes this version compelling is Klassen’s subtle alchemy of mystery, humor, and emotional resonance. The magic of the story comes from his unique concoction of elements, but also from what he left out.

This isn’t the first time Klassen has transmuted the horrors of life into a story for children. Many of his books are fables of consequences, a right for a wrong (intended and unintended). Some horrors are big (like getting eaten by a bear), and some are small (like someone stealing a favorite hat); all have the utmost respect for their audience: children. Klassen never tells readers what to think; instead, he does the opposite—hardly describing time, place, or character. He elicits mood and emotion through delicately crafted clues. His use of color, or lack thereof, sets the tone of his stories—and the eyes of his characters—with their subtle shifts, don’t explicitly tell you what to feel. It may sound cold, but Klassen is careful—right when you think it may be too scary or bleak, he holds your hand or tells a joke.

The Skull isn’t only a transformation of story; it’s a transformation of form. Initially, folktales were told out loud; the only pictures were the ones created in your mind. But the tales have been remixed and reshaped for thousands of years. What makes The Skull special is its possibility for transformation: in form, expectation, and meaning. Is it a chapter book, a graphic novel, an early reader, or a picture book? Is it a book you read out loud to a group of children or one that a child reads alone quietly in their lap? The Skull is all of the above—an intoxicating mixture of the deeply familiar and the totally unexpected.

“In the universe, there are things that are known, and things that are unknown, and in between them, there are doors.” —William Blake

More Moonbow:

A Conversation With Jon Klassen (5 children’s books that shaped him. It’s also a podcast!)

The Books:

The Skull by Jon Klassen (2023)

Italian Folktales by Italo Calvino, translated by George Martin (1980)

Six Memos for the Next Millennium by Italo Calvino (1988)

The Uses of Literature by Italo Calvino (1980)

Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino (1965)

The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, written by Jon Scieszka and illustrated by Lane Smith (1992)

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka (1915)

Support Moonbow

Writing these articles is tough and rewarding work. If my time, ideas, and research are valuable to you, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Can I afford to continue Moonbow? It’s a serious question that’s becoming more pressing with time. I don’t want to offer freebies or bonus content to entice you into becoming a paid subscriber. I want to deliver the best, richest newsletters I can. I want to be excited about what I write. I want you to be excited. If you love reading Moonbow every month, becoming a paid subscriber is the best way to show your support. It’s $5 monthly or $50 annually—or you can become a founding member—and pay any amount you want. If that’s not possible, sharing Moonbow and liking and commenting on articles are other great options.

With gratitude,

Taylor

Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1980 review for The New Republic of Italo Calvino’s Italian Folktales, translated by George Martin

From Calvino’s Introduction to Italian Folktales, 1980, page 33

From an interview between Italo Calvino and Alexander Stille, Saturday Review, March/April 1985

From “Quickness” in Six Memos for the Next Millennium by Italo Calvino, 1988

What a great article, I loved every words!Thank you for writing it! I read Calvino and Kafka when I was younger and I can't wait to read the Skull (in my bucket list).

I love this so very much. Isn’t it one of the miracles of being a child that they’re so trusting and don’t need explanations for everything? They just fill in all the blanks with their creative minds creating something probably even better than the adults could come up with if they tried doing all the explaining. For me at least there’s a lesson in this because I like things tidy. I do not like ambiguous endings, I need all the details. I need instructions and rules! Perhaps that is why I was given such a free thinking, creative child 😉. She is constantly forcing me out of my comfort zone. Thank you for this Taylor!