This newsletter may be “too long for email,” meaning it may appear clipped or truncated in your email inbox. If you see three gray dots, click them to read the full email. Thanks!

Our copy of I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen looks like it’s been through a natural disaster. The edges are frayed, the pages are torn, and the binding has only a few more readings left before it lets it all go. These are the signs of a well-loved book.

Klassen’s fictional worlds are beautiful, spare, funny, and delightful—even when they deal with heavy topics like death, betrayal, guilt, and impending doom, Klassen gently delivers them with skillful humor. His children’s books are far from sentimental, you won’t find him waxing poetic, but Klassen is like a sniper (something he admirably calls The Far Side cartoonist Gary Larson in our conversation); he meticulously works on every detail of his books; no rock is left unturned, resulting in a story that’s deceptively simple, and yet somehow, completely knocks you out in one reading. But you don’t stop there. Once you’ve recovered, you go back for more. And somehow, he will throw you another punch, and you’re left dizzy, astonished that this keeps happening. This makes Jon sound cruel when he’s the furthest thing from it: he’s incredibly kind, thoughtful, and generous; it’s his talent that’s sharp.

In our house, his books are not beautifully displayed on a bookshelf; instead, they’re splayed wide open on a desk, or lying on the floor of our car covered in the dust of goldfish crackers, or lovingly bandaged with masking tape and glue—we’ve been to battle with these books, but in a surprising twist, we’re not fighting against them, we’re fighting alongside them—using them to better understand this weird and wonderful world we live in.

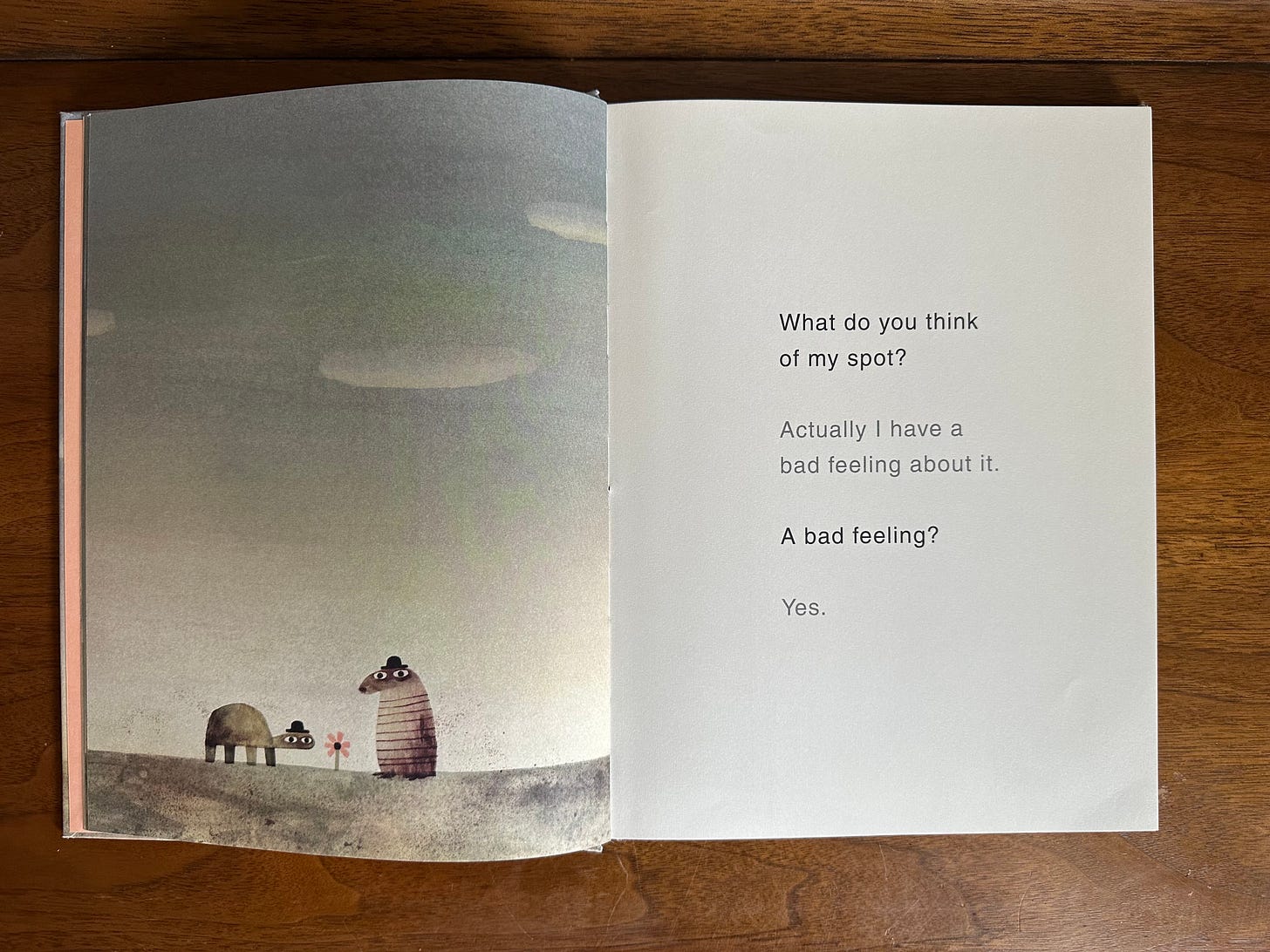

Klassen’s The Rock from the Sky came out in 2021 when we were still reeling from the pandemic and were completely unsure when and how we would ever recover from it. And then here comes this book that was a refreshing antidote without even meaning to be. It’s told in five short stories, and like in his other books, there are animals wearing hats. Not much happens in the stories except for a couple of REALLY BIG THINGS: like a giant rock falling from the sky and a menacing alien arriving soon after. Did the alien come because of the rock? We don’t know. Klassen never explains anything. We’re left to fill in those gaps.

What’s so fantastic about this book is it deals with dread, fear, and scary stuff, but we’re more concerned about how the turtle will deal with his stubbornness and feelings of jealousy, or we’re laughing out loud when he spitefully makes his friends miss out on an epic sunset. But that’s real life, right? Even when something insane happens, we still have to deal with our everyday existence. And through humor, not didactic pandering, The Rock from the Sky delightfully reminds us that life must go on.

It wasn’t Klassen’s intention to make a book that strangely mimicked our wild reality; he just wanted to make a really funny, really good book. But that’s the thing about really good books; they offer something extra to readers precisely when they need it most.

Luckily, I got the chance to talk with Klassen about his work and the five books that were formative for him as a child. You can take a peek at them below, and you can listen to the two of us talk all about them on the Moonbow podcast. Want to know which Archie character he relates to most? The answer might surprise you.

A conversation with Jon Klassen

I chose these pretty fast kind of on purpose. I feel like if I had enough time I'd rethink the list a few times over and end up with 5 other books completely. We didn't have a huge library of kids' books at home when I was growing up. I can't actually even remember a shelf of picture books at all. We went to the library a lot, but that meant that books didn't often get a chance to just be around for very long. As I got older, I had a few I'd go back to and take out repeatedly, but my general experience with books for a long time was pretty transitory. At my grandparent's house, my dad's old room was kept largely how it had been when he was a kid, and one wall in that room was where all the books in their house were kept. Romance novels, paperback mysteries, National Geographics, and there was a long row of book-club picture books from the ‘60s, mostly Dr. Suess, PD Eastman, Roy McKee, those guys. I would sleep in that room when we visited, which was fairly often, and I would pull down piles of books onto the bed and spend hours in there. So some of these books are from that shelf, and some of them are the ones I took out from the library more often, and then some are ones I would buy for myself when I finally got old enough to do that.

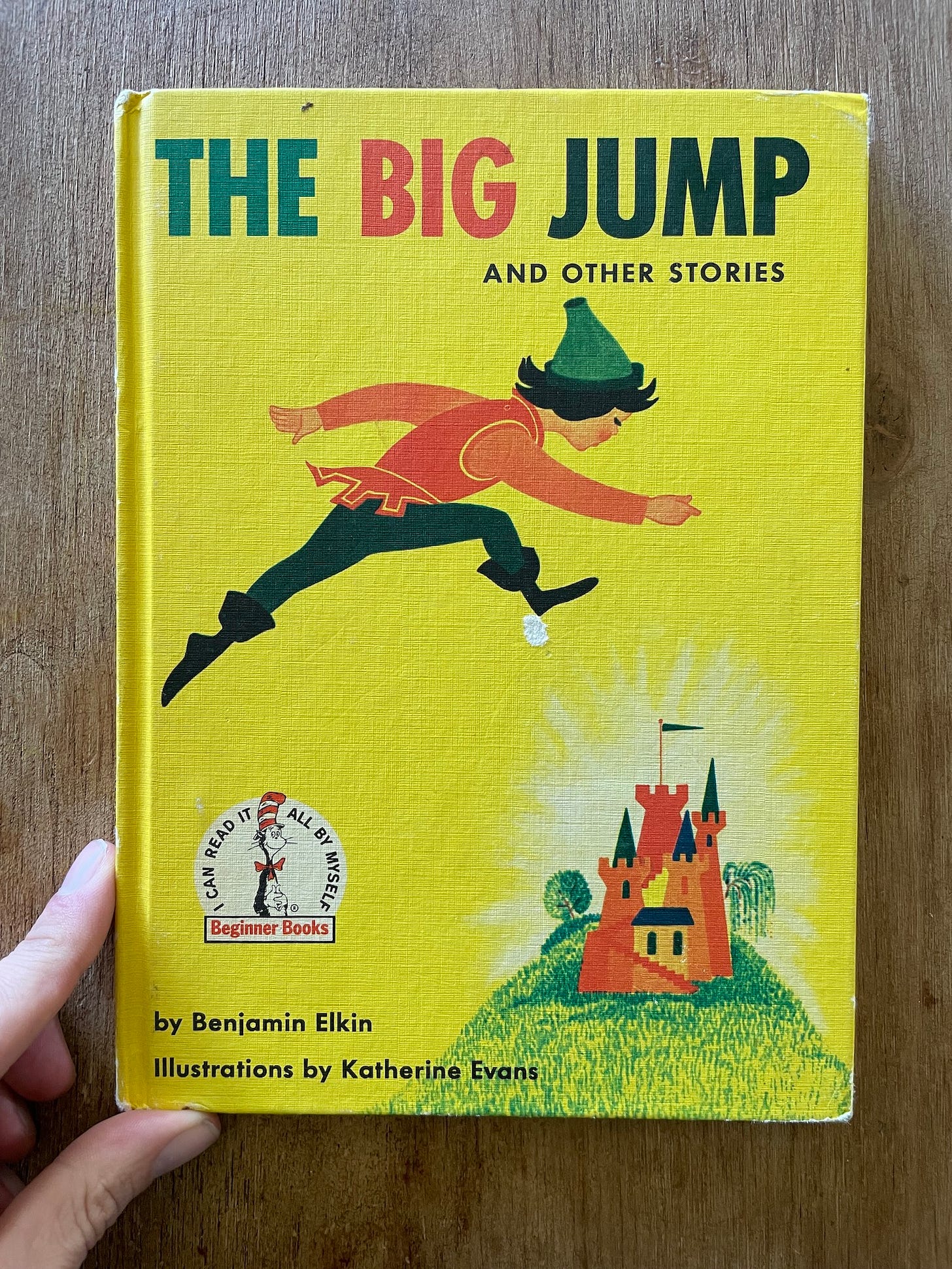

The Big Jump and Other Stories written by Benjamin Elkin, Illustrated by Katherine Evans

This is one of the first books I remember reading or being read to me. Going back to it later, the writing is funnier than I thought. I don't remember the stories being funny, exactly. Elkin liked stories about kings and riddles, he wrote a few books about them, and they always seemed more clever than funny when I was a kid. In this book, there is a good king and a bad king (an amazing setup, I think) and a few trees and ponds, and some kids, and that's basically it. The last story in the book is kind of scary—the main boy in the story ends up inside the bad king's castle by himself —and I was always very into that idea. Interestingly, the first two stories take place during the day, and the last story starts during the day and goes into night, and that is something I do in my books fairly often now, too. This book felt like you'd spent a long time in this kind of nebulous dreamy medieval place. It felt vast and rich to me, not necessarily because of the stories or the illustrations, which are both sparse, but just because of the assembly of the stories, somehow, and the time you'd spent there. I always hoped my books would do that, too, and I tried consciously to do that, especially with the last few.

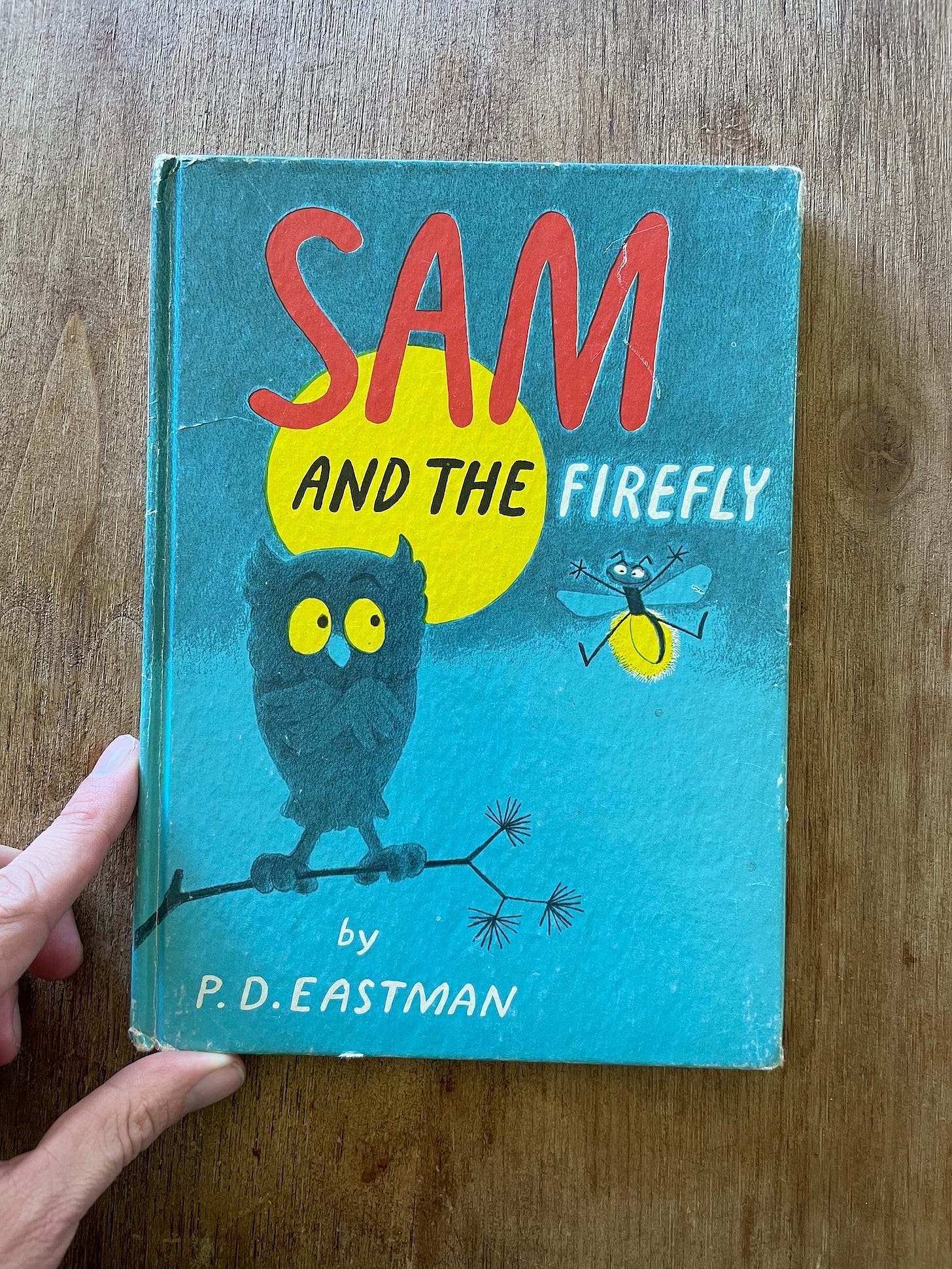

Sam and the Firefly by P.D. Eastman

A huge book for me. Easily my favorite one to pull down from the aforementioned dad shelf —the only other one that came close was Eastman's Go, Dog, Go! —but if I had to rescue one from a fire, this would be it. Again, I don't think it's a story thing here. The story is fine and entertaining. Reading it later in life, I felt a recognition of what Eastman was doing in this one because this was the first book he wrote, and he'd been working in animation until then. The premise here —a firefly writing words in the sky with his light—is an idea probably better suited to animation than a picture book. It takes him like twenty pages to set up the mechanics of it, with the firefly following the owl, who is teaching him what he can do with his light, whereas 10 seconds of animation would've done the same work. But this was a battle I myself went through too, coming from animation and into books. For a lot of years, my ideas were based on something moving over the course of a few panels, because that's what I was used to thinking about. It took a while to start with what still images are best at doing in their own way.

But the real value of this book, to me, is the mood. The artwork is all pencil overlaid on a dark-ish teal, with yellow and white highlights popping out, and it is so soft and beautiful. Eastman is a very straightforward draftsman—he is clear and open in his staging and not prone to fancy angles or rendering or overly-involved techniques. But that plainness combined with this subdued palette and set of materials makes for something that is allowed to feel at once perfectly clear and graphic and also very dreamy and ethereal. Going back to that feeling, again and again, was why I pulled it down so often, and why I still do.

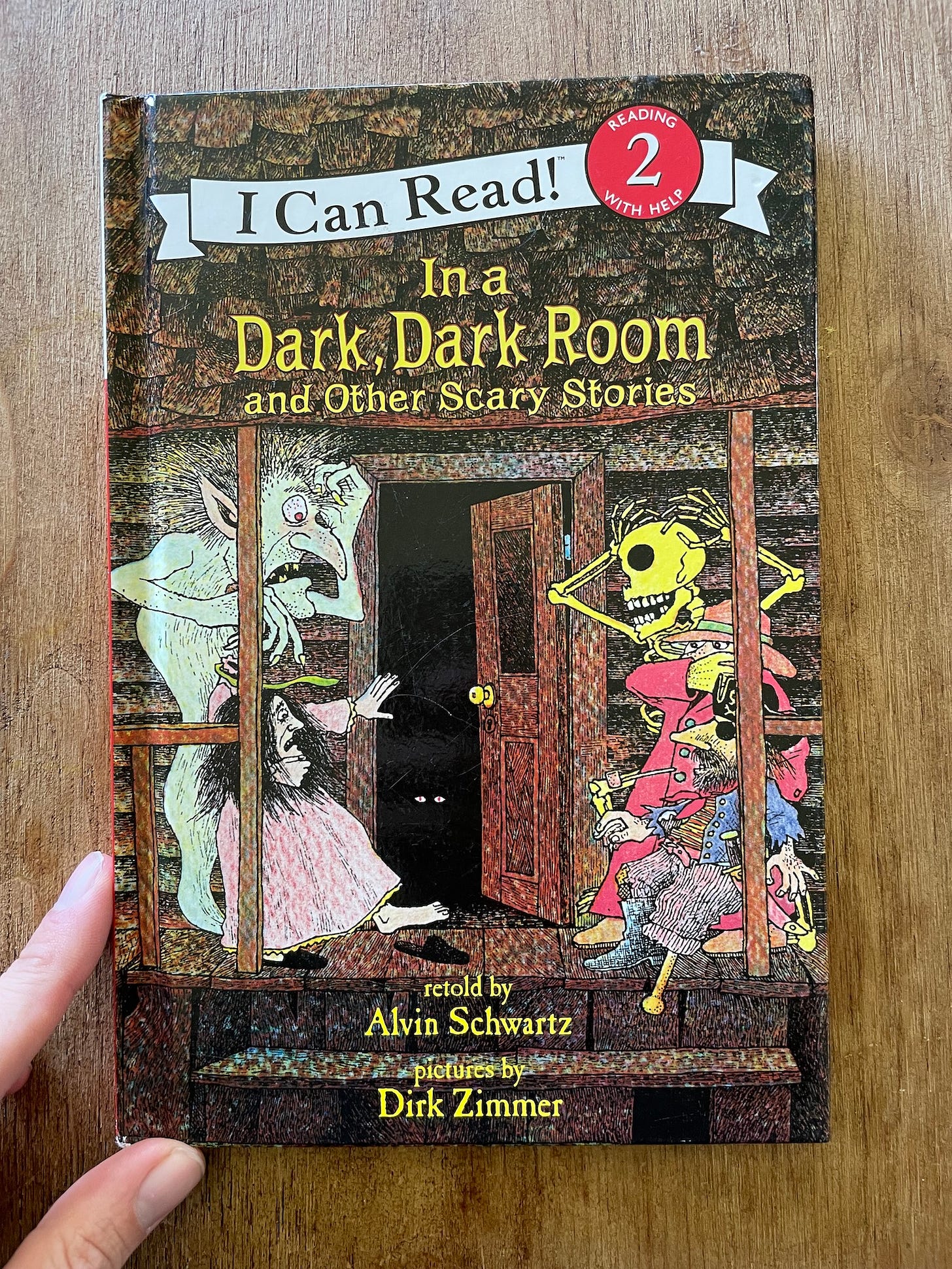

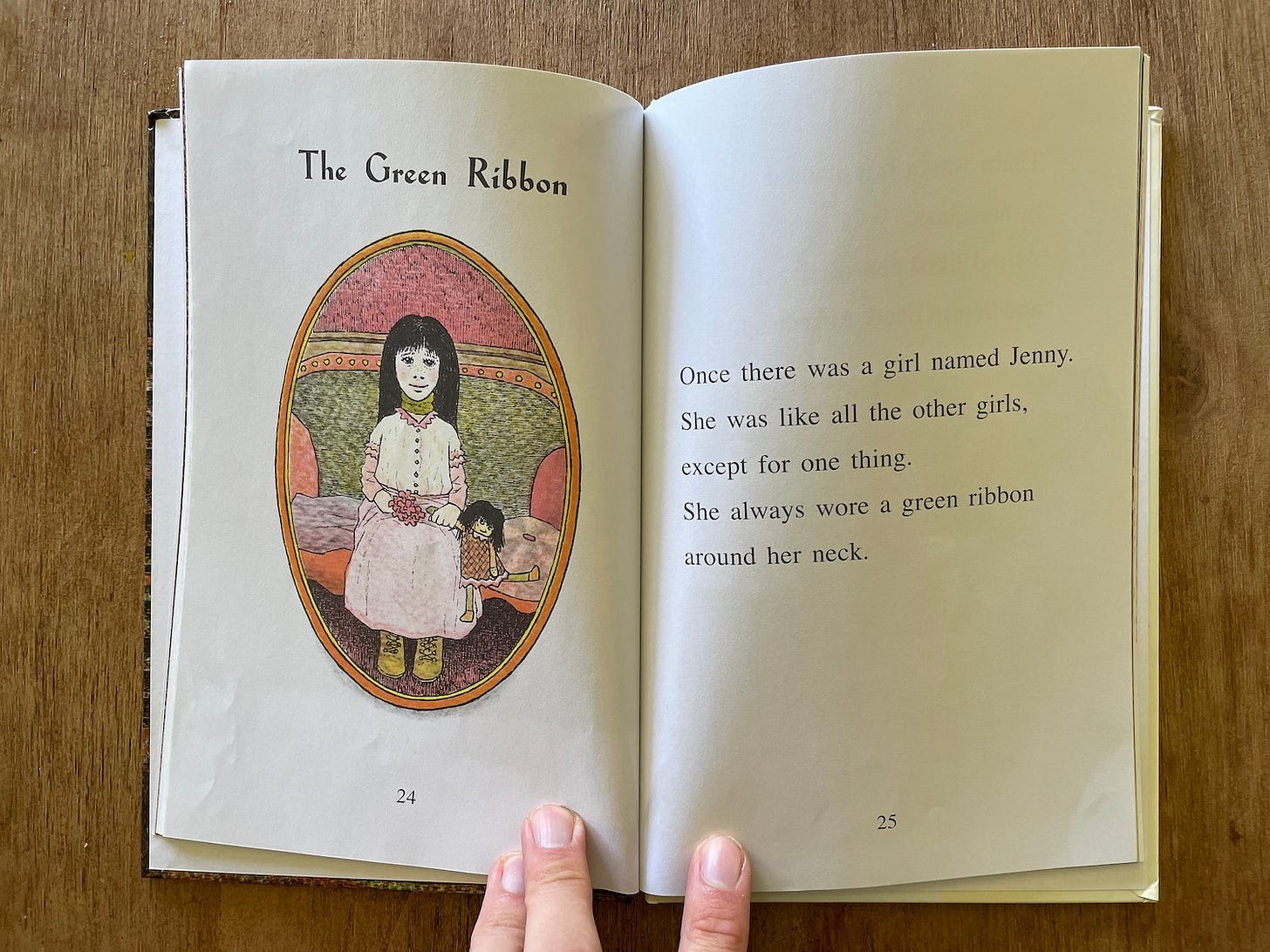

In a Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories retold by Alvin Schwartz and illustrated by Dirk Zimmer

This one isn't as obscure as it felt a few years ago, largely because of the staying power of "The Green Ribbon" story, and I'm very glad for that. It's warranted, too—the writing in this book is so good. The Green Ribbon is a near-perfect nine pages, and told so calmly. It's also an interesting one for me to revisit because it's one of the only books I would return to often as a kid where I knew I didn't really like the look of the illustrations. The pictures have this early ‘80s grime on them, when Sendak's mark-making and hatchwork was still reverberating around to people who didn't handle it as well as he did, and the colors are all weird and everyone's features are a little grotesque...it's not a great-looking book, I don't think. But the plainness of the writing, that Schwartz wasn't trying to make anything sound any scarier than it was...there was and is a quietness to the text that I loved, and it's the first time I remember enjoying being scared. When I was a kid (and this is still true) I got scared, badly scared, by stories where the teller didn't know how or when to hold back, when they're just in the business of traumatizing you. An experience like that isn't scary because the story itself is scary, it's scary because you're wondering why the people that made it enjoy doing that to their audience. It's a deeply lonely feeling. But when a story is told well, and crafted, and controlled, you can take your audience, including children, almost anywhere, and it's a very hopeful and empowering thing. This book made me feel brave, and I was proud that I liked it.

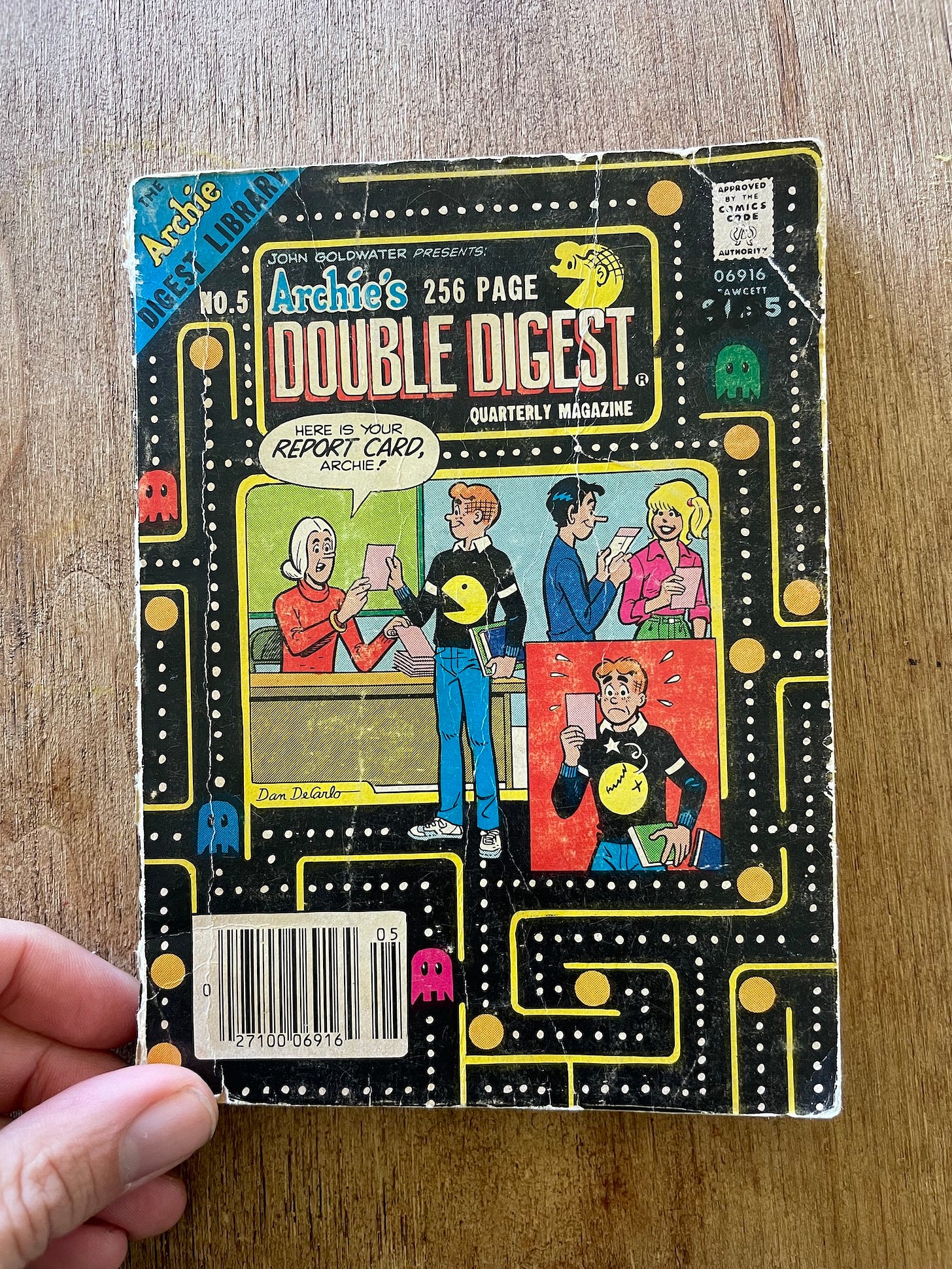

Archie's Double Digest

It wasn't this Double Digest in particular that had anything special about it. I had dozens of these, but I did have this one too and I remember reading it a lot. Archie comics are so weird. They are an ambient experience. You're not in it for the stories, really, and you're not in it for the laughs, cause they're not that funny, and I read them before my motivation would've been to look at the drawings of the girls, or at least I don't remember that being the reason. I have no idea what I got out of these comics, but I read them constantly, over and over, so I'm putting them on this list because there's no way they didn't have some kind of profound effect. They were just easy to sit in - you knew that nothing was really going to happen to anyone in them, and maybe I liked that.

One thing I note now, and did a little bit back then too, is that a lot of the stories took place in these wide open clean-looking neighborhoods where it looks like the cement had just been poured. The characters are, a lot of the time, just walking or standing around together on these giant white sidewalks between each other's houses, heading for school or Main Street or the beach. It looked like a wonderful speed of life, and it was also kind of surreal.

Spending that time in my dad's room that I mentioned earlier, in the house where he grew up, and later actually living in Niagara Falls, which at the time felt like a town that had stopped changing 30 years prior, I got very preoccupied with the ‘50s and early ‘60s, when my dad was a kid, and I wondered all the time what things would've felt like back then, when things were new. Maybe I thought they would've felt like an Archie comic.

The Far Side by Gary Larson

Again, this is just a book of his that I had growing up, but any Far Side collection would have fit here. Looking back, if I had two teachers on visual storytelling, they were for sure Gary Larson and Bill Watterson. When I have to actually "draw" anything, like with lines, I think I still try to draw like Watterson, and think about how he did trees and tufts of grass and shoes and things (I can't actually draw like that which is why I don't show those drawings). But I'm choosing Larson here because when I look at my own book work, that I do myself, I see way more Gary Larson. Not in the drawing, exactly, but in the approach to a joke, or the choice of a moment in time to show, which I think is way more important than how the thing is drawn. Larson was so, so good at choosing when, in a story, is the funniest possible moment to show, and it's almost never in the middle of something happening. It's either before or after it happened. When I was going from animation into picture book illustration, that was the main thing I got excited about. In animation, you have to (or at least they want you to) show everything: the beginning, middle, and end of an event. It's very very hard to leave things out. But when I started getting into picture books, it became clear pretty fast that this was a medium where you could turn a page and the thing had happened in between the turns, and that's actually what books are good at. All of a sudden I had an outlet for everything The Far Side had been showing me all those years.

The other thing about Larson that I took, a little bit, was emotional restraint. Larson almost always took his characters' eyes away somehow, either just didn't draw them or put them behind opaque glasses, and he made their bodies kind of inflated enough that they weren't really expected to do much with them besides just stand there. The result is that you aren't given any clue, visually, as to what they're feeling like when they're in a situation, but you know how they're feeling anyway because you relate, and that's the laugh. It wouldn't be funny if the characters were going nuts in the drawing. It's way funnier if they're just looking blankly, resigned to the horror of life. I do give my characters eyes because I feel like I need some way to grab a younger audience's attention, but my eyes are often blank, resigned in the same kind of way, and the characters aren't really able to do much with their bodies at all, and that, I think, I got from The Far Side.

Thanks, Jon! Jon’s next picture book The Skull comes out this July (we can’t wait!). His collaboration with Mac Barnett on the fairy tale The Three Billy Goats Gruff (2022) was one of Moonbow’s “Best Books of 2022,” and their book The Wolf, the Duck, and the Mouse (2017) is one of my family’s favorite picture books of all time.

Jon also has a new television show, Shape Island, on Apple+, inspired by his shape book series: Triangle, Square, Circle (all written by Mac Barnett), that’s delightfully funny and intoxicatingly ambient.

Moonbow is a reader-supported publication. It exists because of the support of generous readers like you! If you enjoy Moonbow, the best ways you can support it is to subscribe, share this newsletter with a friend, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription.