As fond as I am of digging deep into picture books, I know they’re most pleasurable when read for an experience rather than for meaning. That’s not to say they don’t have meaning and shouldn’t be challenging and thought-provoking, but that the enjoyment is in the feeling. And contrary to what some may think, it’s often the more abstruse books that provoke us the most. Obscure books don’t tell how to feel; instead, they elicit emotions through abstractions, allowing space for readers to decide things for themselves. Not everyone enjoys these types of stories. Experimental art can be a work of genius to some and pretentious garbage to others. Consider Goodnight Moon (1947) by Margaret Wise Brown: a polarizing book despite its steadfast spot on best-seller lists since the early ‘70s. Goodnight Moon is one of my favorite books, but even I didn’t always understand its purpose. Despite finding it mysteriously hypnotic as a child, I wasn’t sure what all the hype was about. It wasn’t until I had children and repeatedly read it to them that it clicked. With each reread, we have new observations, questions, and feelings. We’re continually drawn to the enigmatic “great green room” without exactly knowing why. It’s fun to theorize, but we don’t need to. The book is “about” experiences: the experience of going to bed and the experience of reading it at bedtime.

In the Half Room (2020) by Carson Ellis works similarly. You can’t really explain what it’s about. There are many half things: a half-moon, a half-room, a half-woman, a half-cat—none of which are explained. Like Goodnight Moon, the book relies on rhythm and atmosphere rather than plot. Although, when the half-woman (serendipitously?) meets her other half and SHOOOOOPS into her whole self, it’s tempting to think the book is about the joy of feeling whole, of becoming your “true” self, but that’s not the point, especially because Ellis makes sure not to unite the two half-cats at the end. In the Half Room is an incantation: a nonsensical dreamlike spell of words that produce an effect—that effect depends on the reader—but for me, it’s a befuddling delight.

The experimental poet Gertrude Stein also perplexes readers. (Stein was a huge influence on Margaret Wise Brown.) She wanted readers to feel her words rather than understand them. She believed too much interpretation robs readers of enjoyment. To read the works of Stein, Brown, and Ellis is to read with the body. There’s a pulsating intertextuality between them. It’s not the words that are most meaningful but the sounds of the words. The textual enjoyment is in listening to and feeling the rise, fall, and unexpected breaks in the rhythm.

Here’s Stein in a 1934 radio interview:

Look here. Being intelligible is not what it seems. You mean by understanding that you can talk about it in the way that you have a habit of talking, putting it in other words. But I mean by understanding enjoyment. If you enjoy it, you understand it. And lots of people have enjoyed it so lots of people have understood it. . . . But after all you must enjoy my writing, and if you enjoy it you understand it. If you do not enjoy it, why do you make a fuss about it? There is the real answer.

I love that. It’s almost ironic coming from a woman as complex as Stein, but it’s true:

If you enjoy it, you understand it.

“The light of the half moon shines down on the half room.”

You can listen to me read In the Half Room in today’s episode—it starts at minute 5:45 of the recording. (I’ve learned from reading this book many times that there is no way to sound cool while reading the word “SHOOOOOP” out loud.)

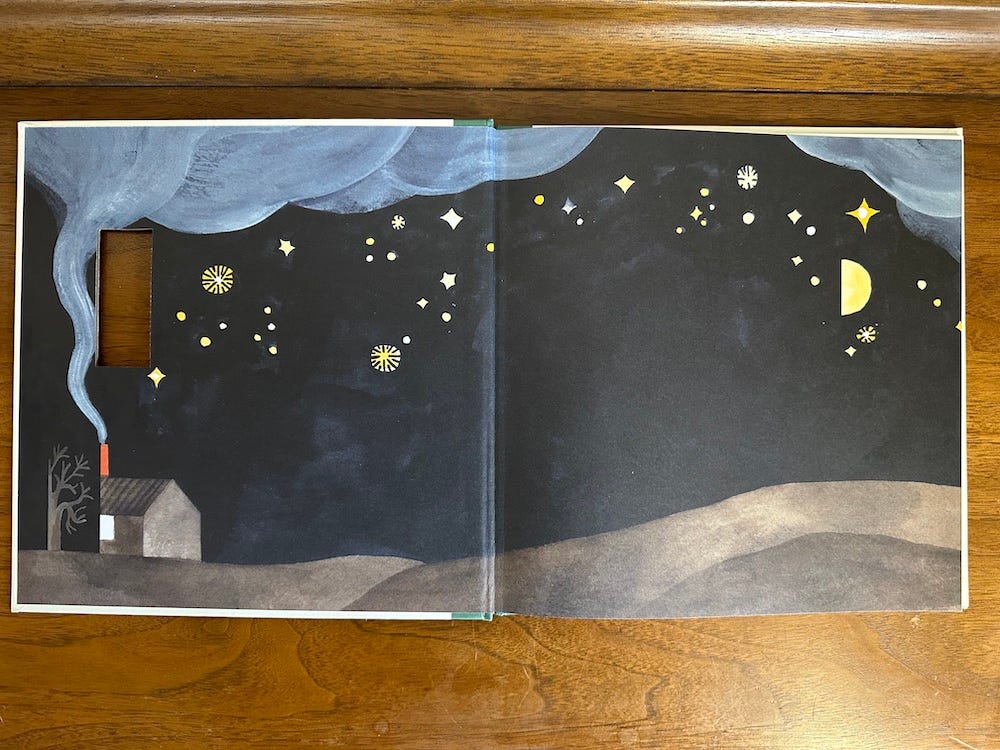

Speaking of houses in the moonlight…

One of Gertrude Stein’s most famous poems is [a light in the moon] from her book Tender Buttons (1914). It’s great, but it’s not my favorite. It’s hard to choose, but mine is probably another one of her moony poems: [the house was just twinkling in the moon light], or at least it’s one of my favorites, especially to read aloud. You can listen to me read it here:

[the house was just twinkling in the moon light]

by Gertrude Stein

The house was just twinkling in the moon light,

And inside it twinkling with delight,

Is my baby bright.

Twinkling with delight in the house twinkling

with the moonlight,

Bless my baby bless my baby bright,

Bless my baby twinkling with delight,

In the house twinkling in the moon light,

Her hubby dear loves to cheer when he thinks

and he always thinks when he knows and he always

knows that his blessed baby wifey is all here and he

is all hers, and sticks to her like burrs, blessed baby

If you enjoyed this article you might also like:

Moonbow is a reader-supported publication. It exists because of the support of generous readers like you! If you enjoy Moonbow, the best ways you can support it is to subscribe, share this newsletter with a friend, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

Share this post