The Sound of Picture Books

"A good picture book can almost be whistled"

Moonbow is a reader-supported publication. It exists because of the support of generous readers like you! If you enjoy Moonbow, the best ways you can support it is to subscribe, share this newsletter with a friend, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

If you’ve missed any recent issues, you can always find them in the archives.

The Sound of Picture Books

A good picture book can almost be whistled…All have their own melodies behind the storytelling. —Margaret Wise Brown

Childhood is experimental. Children use their imaginations to envision new possibilities and to transform problems into solutions or, oftentimes, to transform themselves. So it’s only fair that children’s books should reflect that same level of creativity and experimentation. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case. There are plenty of dull, unimaginative books made for kids. I’m sure you’ve read them. If you’re a parent, you’ve probably kicked a fair share of them under your child’s bed, hoping they remain hidden amongst the dust bunnies, never to be read again. But thankfully, there are also bold, exhilarating, sophisticated books for children, many of which were made during the 1940s-1970s, the golden age of picture books.

Picture books are told through visual language—a term coined by the political scientist Robert Horn for a “language based on tight integration of words and visual elements". What makes the picture book such a unique art form is how the dynamic relationship between text and image is interpreted. Most picture books are written by an author and then interpreted by an artist into images. But in a good book, the text and images leave space for even more interpretation: first by the person reading it aloud (usually an adult) and then by the child.

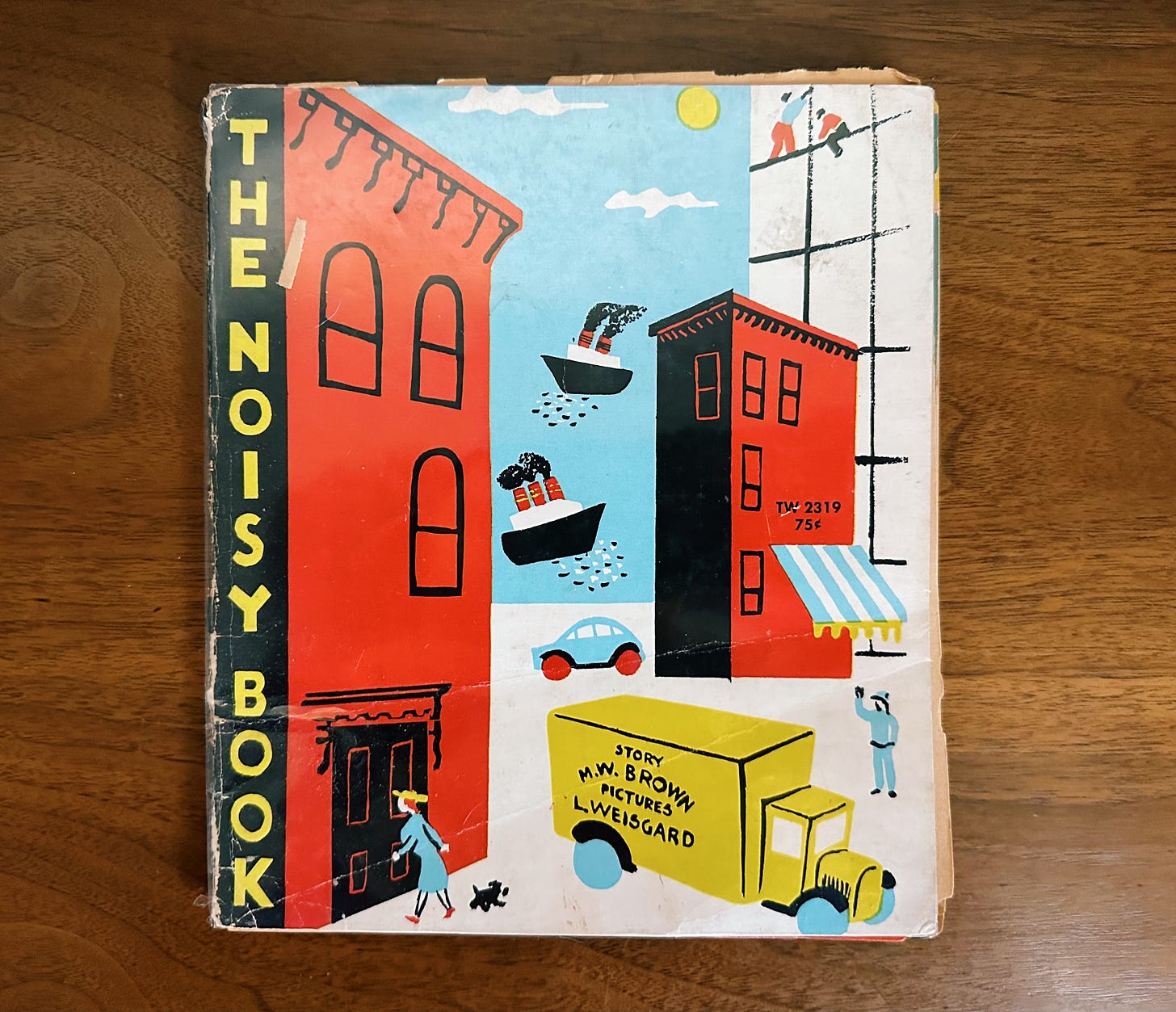

Many talented artists of the golden age used picture books to explore visual thinking. In the 1950s, the graphic designer Paul Rand and his then-wife Ann wrote a series of books, Sparkle and Spin: A Book About Words (1957), Little 1 (1961), and Listen! Listen! (1970), to demonstrate “a playful but sophisticated understanding of the relationship between words and pictures, shapes, sounds, and thoughts.” (Children’s Picturebooks: The Art of Visual Storytelling by Martin Salisbury and Morag Styles via The Marginalian). These relationships were uniquely utilized by the progressive children’s book author Margaret Wise Brown, who understood that the sounds of her words were just as important as the words themselves. In the Noisy book series, illustrated by Leonard Weisgard, Brown combines voice, art, and story to communicate sound. In The Noisy Book (1939), a dog named Muffin gets cinders in his eyes and has to wear a blindfold, forcing Muffin to rediscover the world around him through sounds. In The Quiet Noisy Book (1950), Muffin wakes up in the morning to a very quiet sound. Brown asks the reader to guess what the sound might be, but she asks about things we don’t typically think of as sounds. Was it butter melting? Was it a grasshopper sneezing? Was it a skyscraper scraping the sky? She invites readers to be curious and to see the world through a sound point of view.

Brown also understood that the musical element in language and literature were well-suited for radio and television. She could rewrite her stories and songs in fresh, imaginative ways by adding sound effects and working with singers. She imagined it would be like ballad singers suddenly showing up at children’s Story Time.

The popular folk singer Burl Ives recorded Brown’s Two Little Trains for Columbia Records in 1951. He was so pleased by the experience he wrote to her:

“I am sure there is a dimension in children’s books, especially your books, which must delight any adult with imagination.” (Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon by Leonard Marcus, 1992)

Brown’s musical interests continued up until her death in 1952. She had many of her books set to music and planned to adapt them for radio and television. One of my favorites, Wait Till the Moon Is Full (1948), was one of them. Sadly, we never had the chance to see what she would have done with animation. Surely, she would have pushed the limits of the form. But we can listen to the recorded version!

To better understand how music and sound design can enhance film adaptions of picture books, let’s look at the work of the famous animator Gene Deitch.

Gene Deitch was a talented animator and illustrator, best known for his animations of Tom & Jerry, Popeye, Where the Wild Things Are, Moon Man, and “Tom Terrific,” his character for the show “Captain Kangaroo.” In 1961, he won an Oscar for his touching animated film “Munro.” In his impressive six-decade career, he made countless cartoons and many film adaptations of children’s books. He was also a lover of jazz.

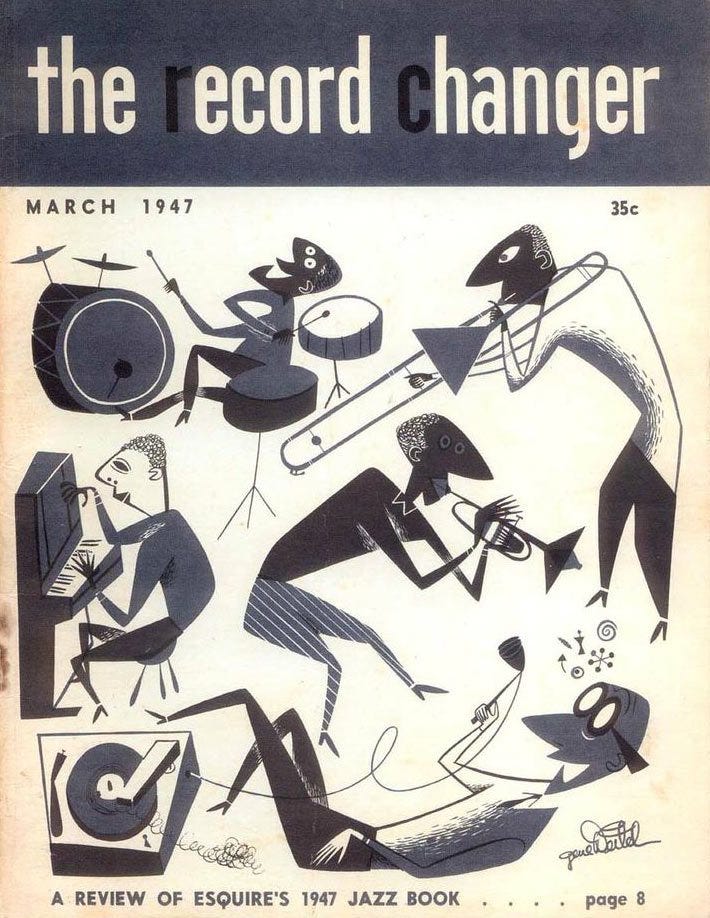

In an interview for The Comics Journal in 2008, Deitch talks about his obsession with jazz music from an early age. Like many children of the ‘30s and ‘40s, he loved collecting records, and it was in a record shop that he discovered The Record Changer magazine, a dull, dry-looking trade magazine that he felt was desperately in need of funny cartoons. He went home and created a series of over-the-top-looking characters that he submitted to the magazine’s editor. The risky move paid off. And not only that, it turned out that the kind of people who were into animation and the arts were also the kind of people who read The Record Changer magazine. It was through his work for the magazine that Deitch’s career in animation began.

Deitch credits The New Yorker cartoonist and children’s book author and illustrator William Steig as his earliest inspiration—specifically, the extremely caricatured faces in Steig’s 1945 book, Persistent Faces. Saul Steinberg, John Hubley, and Jim Flora were also his influences (and sometimes his collaborators). What’s interesting about Deitch isn’t his unique drawing style but his unique ability to replicate anyone’s drawing style. He was a style chameleon. “I don’t have a “Gene Deitch style,’ he told The Comics Journal, “That’s part of doing film work.”

Deitch became a major figure in animation during the golden age of children’s books, and in 1968 he joined Weston Woods Studios, where he and founder Morton Schindel, along with a team of animators and writers, creatively adapted many of the exhilarating picture books of that period.

Here are just a few:

Where the Wild Things Are (Maurice Sendak)

In the Night Kitchen (Maurice Sendak)

Moon Man (Tomi Ungerer)

The Three Robers (Tomi Ungerger)

The Hat (Tomi Ungerger)

The Beast of Monsieur Racine (Tomi Ungerger)

Strega Nona (Tomie dePaola)

Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (William Steig)

A Picture for Harold's Room (Crockett Johnson)

In the film, The Picture Book Animated (1977), Deitch talks about his unique hand-crafted techniques and philosophy for adapting children’s books:

I love how Deitch describes his process for extracting the essence from these great stories.

“We’ve tried only to project the ideas from the book so that when the child returns to it after seeing the film, he will love it more and see it more.”

His goal was not to make the films better than the books but to make the films a reason to love the books even more—what a generous act of storytelling.

Deitch had a unique way of telling these stories through music and sound. His experiential style wasn’t always popular (look up his work for Tom & Jerry), but his scores for the animated children’s books are less polarizing (or at least most of them). In The Picture Book Animated, Deitch explains his process for scoring his adaptation of the wordless picture book Changes, Changes (1971) by Pat Hutchins. The two wooden characters are without elbows and knees, inspiring Deitch and his team to create jerky movements not only in the drawings but in the music too. And since everything in the book is made of wood, they decided to only use pieces of wood for the music: a xylophone, a marimba, a wooden crate, woodblocks, rattles, and a handcrafted collection of various-sized 2x4 wooden planks designed to be struck by a wooden mallet (which Deitch called the “plank-o-plonker”). These innovative instruments and sounds reflected the “creative discipline of the wooden man and women, whose carry-on spirit helps them solve each problem by the rearrangement of each set of wooden blocks.” (The Picture Book Animated, 1977).

Creative problem-solving is an essential part of the adaptation process. There’s a hidden tension within each story, and it’s Deitch’s job to unearth it through his unconventional visual and auditory techniques.

He mentions this when referring to his storyboards:

“And in the captions, I indicate the relationship of spoken words, sound effects, and music to the film action.

An example of this is in his adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are.

In this clip, Deitch recalls his long walks with Sendak through the streets of Prague in 1969, where they talked about ideas for the film. One hint that Sendak gave to Deitch was that “In this story, everything is Max!” and “for the music, think of {the song} ‘Deep Purple.’”

In 1933, “Deep Purple” was a popular piano composition by the jazz composer Peter DeRose. It’s the style of music you’d hear in a sweet little hotel café in the ‘30s. This clue from Sendak helped Deitch discover the musical and sound devices that would evoke the distance between Max and his parents. In Where the Wild Things Are, we never actually see Max’s parents, but we hear his mom react to his increasingly mischievous behavior when she yells, “WILD THING!” and sends him to bed without supper. As Deitch points out in Picture Book Animated, we don’t know what Max’s parents are doing, but we know they aren’t with Max. Perhaps that’s why he’s acting out: he’s bored and looking for attention. Deitch experimented with a muffled sweet 1930s melody that he increasingly distorts to emulate Max’s growing rage and journey into fantasy. And for the sound effects, he restricted himself to domestic sounds— sounds Max could make at home and that express his feelings of isolation. Sounds like: a gas oven lighting, a door slam, a car starting, a baby crying—are repeated over and over, intensifying the music and the listener’s experience. These uniquely handcrafted reverberations, combined with the romantic jazz melody and the gruff voice of the narrator, illuminate the story in a fresh new way.

Here is a snippet of Dietch’s original 1973 soundtrack for the film:

The film was a success with critics and, most importantly, with Sendak. But despite this (and the five long, arduous years it took to make the film), in 1989, Sendak decided to scrap Deitch’s soundtrack in favor of one composed and narrated by Peter Shickele.

The only video I could find of Peter Shickele’s version is on Apple TV. You can watch the trailer for free here.

I won’t get into the weeds over this—there’s a lot of great information from Deitch’s point of view on his website, but I think it’s an interesting matter of taste. There’s no questioning Sedak’s genius. He clearly had strong, and sometimes conflicting, opinions about how his stories should be portrayed. That’s what makes his work so memorable. But for what it’s worth, I prefer Deitch’s experimental soundtrack.

So why did Sendak change his mind? The reason remains a mystery. My guess is that, despite its success, somewhere along the line, someone decided it was “too avant-garde” for children, too sonically assaultive. But similar things were said of the book Where the Wild Things Are (1963), and it wasn’t like Sendak to shy away from dark, disturbing themes. Perhaps the sounds lacked the simple elegance Sendak always strived for.

In Sendak’s original notes to Deitch, he wrote, “the film should be ponderous, unsettling—not romantic.” And that’s precisely what it was until Shickele’s water-downed version replaced it. Deitch’s distorted montage of homemade sounds creates an unsettling, eerie feeling—but it’s not scary—it’s enchanting.

Regardless of the switch, what’s most interesting to me, is how sound communicates abstract ideas. Both Deitch and Brown used sensory language to create vivid imagery. And they recognized that young children make sense of the world through their sensations. Ask a small child, “What is the sound of a bee wondering?” They’ll know the answer.

Bonus Weston Woods Studio content:

Deitch’s Tomi Ungerger: The Storyteller

Deitch’s adaptation of Smile for Auntie by Diane Patterson (great sound effects!)

To keep Moonbow ad-free, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Can’t afford it? Sharing the newsletter with friends and on social media is another great way to show your support. Thank you for reading Moonbow!

This was wonderfully researched, Taylor -- and such a great element to dig into further to begin with. I think the sound of a picture book is one of the most important contributing elements (maybe the *most* important) when it comes to the joy of reading one aloud -- there are some that just absolutely sing, or yes, whistle, and they're all the more magical because of it.

Thanks, as always, for a great read!

My parents inserted beautiful tunes when reading “Where the Wild Things Are” and I sing the same tunes to my kids ❤️