Hi everyone! I’m back with a new issue of Moonbow! I know it’s been a while—thanks for sticking with me. I’m kicking things off with a special feature with the incredible author-illustrator Jess Hannigan! Jess put a lot of thought and care into this, and I think you’re really going to enjoy it. As always, Moonbow features are free to read and listen to. However, they take a lot of time to plan, write, record, and edit. If you’d like to read more of these in the future and are in a position to support this publication financially, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Otherwise, sharing this article with friends and on social media is appreciated. Thanks!

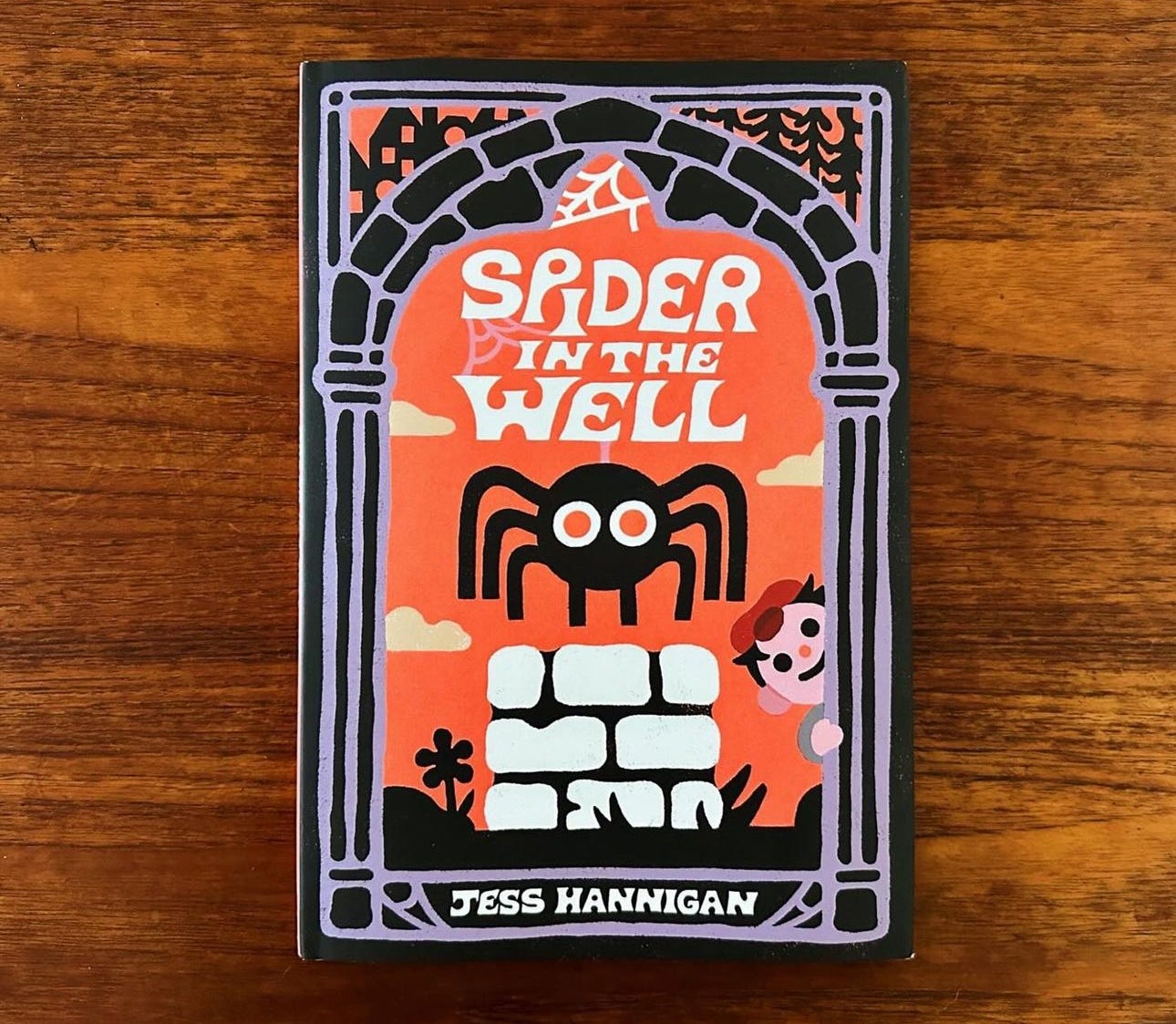

The children’s book author-illustrator Jess Hannigan is full of delightful contradictions. In her terrific debut picture book, Spider in the Well, which came out earlier this year, she wrote, “To my mom, Bev, for letting my ego get too big. Look what you did.” It’s rare for a book dedication to make you laugh out loud. But the funny truth is that Hannigan is refreshingly humble. Throughout our conversation, she was open about how lucky she’s been and that she’s still figuring things out. For someone new to the scene, she’s incredibly thoughtful and well-spoken. Toward the end of our chat, she openly reflected on the process of writing about the children’s books that shaped her, “I can see why you love writing about books.” she said. “I’ve learned a lot about myself. I hope someone listens to this and finds me interesting.” After talking to her, I can’t imagine anyone thinking otherwise.

Hannigan may appear to be an overnight success, but she’s been writing stories since she was a little girl. “This is the only thing I’ve ever wanted to do,” she said while talking about how she got into making picture books. “When I was 10, in grade 5, here in Ontario, we had a project that was like, What do you want to be when you grow up? I wrote illustrator—whereas some people don’t even realize that being an illustrator was a job, but I was like, no, that’s what I will be.”

She became a rising star at Sheridan College, where she studied illustration. Her graphic style and dark humor got the attention of a famous alumnus, the children’s book author-illustrator Jon Klassen, which eventually landed her an agent. Hannigan is quick to admit that Klassen’s support and guidance have been instrumental in her success, but that doesn’t negate her hard work and talent. Anyone with a pulse on picture books can see she’s someone to watch.

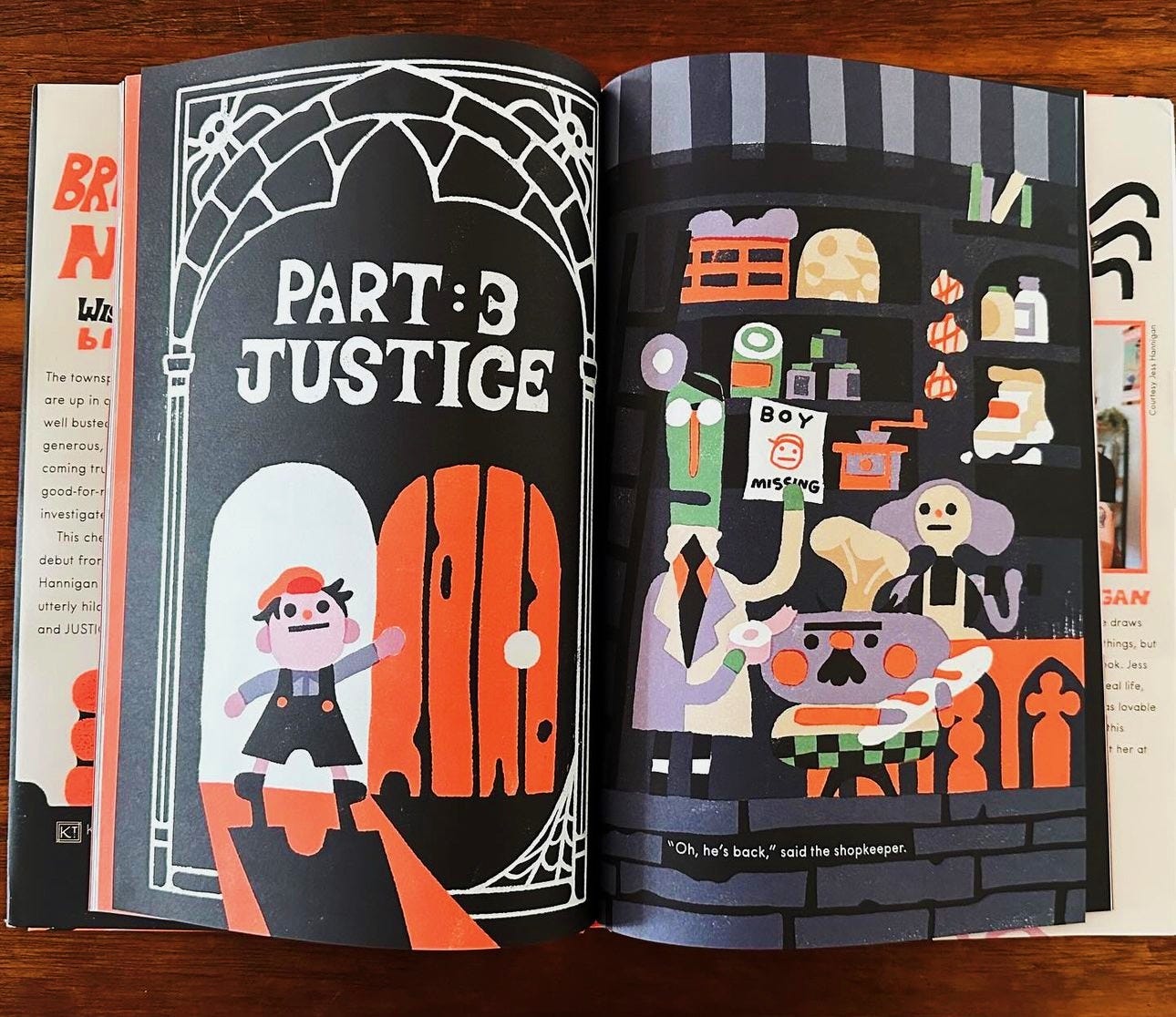

When it comes to children's books, you don’t typically see blackmail or extortion, but Hannigan’s Spider in the Well has both. In this hilariously subversive folktale, a newsboy has been tricked by the town of Bad Göodsburg into performing multiple jobs (he’s also the chimney sweep, the shoe shiner, and the milkman). When news breaks that the wishing well is broken, the townspeople—a baker, a shopkeeper, and a doctor—are aghast that their charitable wishes won’t come true, but when the newsboy goes to fix the well, he finds a spider inside hoarding gold coins. In defense, the spider quickly exposes the townspeople for their lies, revealing that their wishes weren’t altruistic but embarrassingly selfish. Enraged, the newsboy plots revenge in the name of “JUSTICE!” With the clear upper hand, he cleverly makes a move that frees him of labor and leverages the spider’s wrongdoing into a shared wealth plan for them both.

It’s one of the saltiest, most satisfying picture books, with vibrant artwork, sly details, and a shrewd sense of humor similar to Tomi Ungerer and James Marshall. Even as a debut author-illustrator, Hannigan is deeply thoughtful and curious about the potential of the picture book art form—the industry is lucky to have her.

Hannigan could have easily turned this story into a moral lesson. Instead, she has us question right and wrong and reminds us that sometimes, the line between the two isn’t so clear. It’s a risky move. Many well-intentioned adults want to draw a hard line between good and bad, especially when teaching children, but we know (and kids know, too) that it’s often more complex than that. When I asked her if she’d received any pushback, she said, “Yes! Some adults don’t get it. But so far, kids love it. It’s cool to have lessons in your book—it’s fine—but you also have to make it a good story.”

I was curious about what she thinks makes a good children’s story. “I love a visual gag to draw a book forward,” she said. “I’m working on a book right now that’s sort of a visual gag, and it’s so much fun because that’s how the idea started. But then I can tell a story within that as a vehicle and also make it pretty and funny and escalate the plot. I think those are all the special magic ingredients that make a book good.” The vehicle, or gimmick, as she also refers to it, should be unique to the picture book form. Whether it’s the dynamic relationship between text and image, the layout, trim size, pattern repetition, or surprising page turns, each helps to inform the reading experience. Throughout our conversation, Hannigan and I explore how these five books utilize form and function and how those innovative techniques work to tell a good, sometimes great, story.

(Please note: a few light edits were made to podcast quotes for clarity)

I had the pleasure of getting a sneak preview of Hannigan’s upcoming picture book, The Bear Out There (April 2025), and it’s a stellar example of all the techniques she and I talk about. I have not laughed more while reading a picture book since The Stupids Step Out (1974) by James Marshall. Bravo, Jess!

Here’s Jess:

The process was easier than I thought it would be because I have a terrible memory, so there was much less to choose from than you would think. The ones I think are likely responsible for doing a lot of shaping to my brain are a blend of three childhood favorites and two that I discovered in the last 5 years. A huge influence on my work is movies and TV (“SpongeBob SquarePants,” “The Muppets,” etc.), but these books probably had a hand in my brain, too. I didn’t pick any Tomi Ungerer because Shawn Harris just did his 5 Books, and he had The Three Robbers already. I didn’t want to bore anybody to death with repetition, so I left it out, but Tomi is an all-timer, obviously, even though I also just learned about him within the last 5 years. We were mostly library people, but we had a small collection of Dr. Seuss books, Little Golden Books, fairy tale compilations, and some of my mom’s from the ‘70s. Funny books were usually the kind of picture book I cared most about unless the illustrations were especially beautiful, like the wonderful vibes from The Cow Who Fell in the Canal by Phyllis Krasilovsky, which almost made it onto this list if I didn’t have two books with cows in them included already. I think if we’d had any scary books like In a Dark, Dark Room, or Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, those absolutely would have been favorites, but I don’t know why we never had anything like that. It’s especially weird, considering what a horror buff my mom is! She has great taste and is a fantastic book performer.

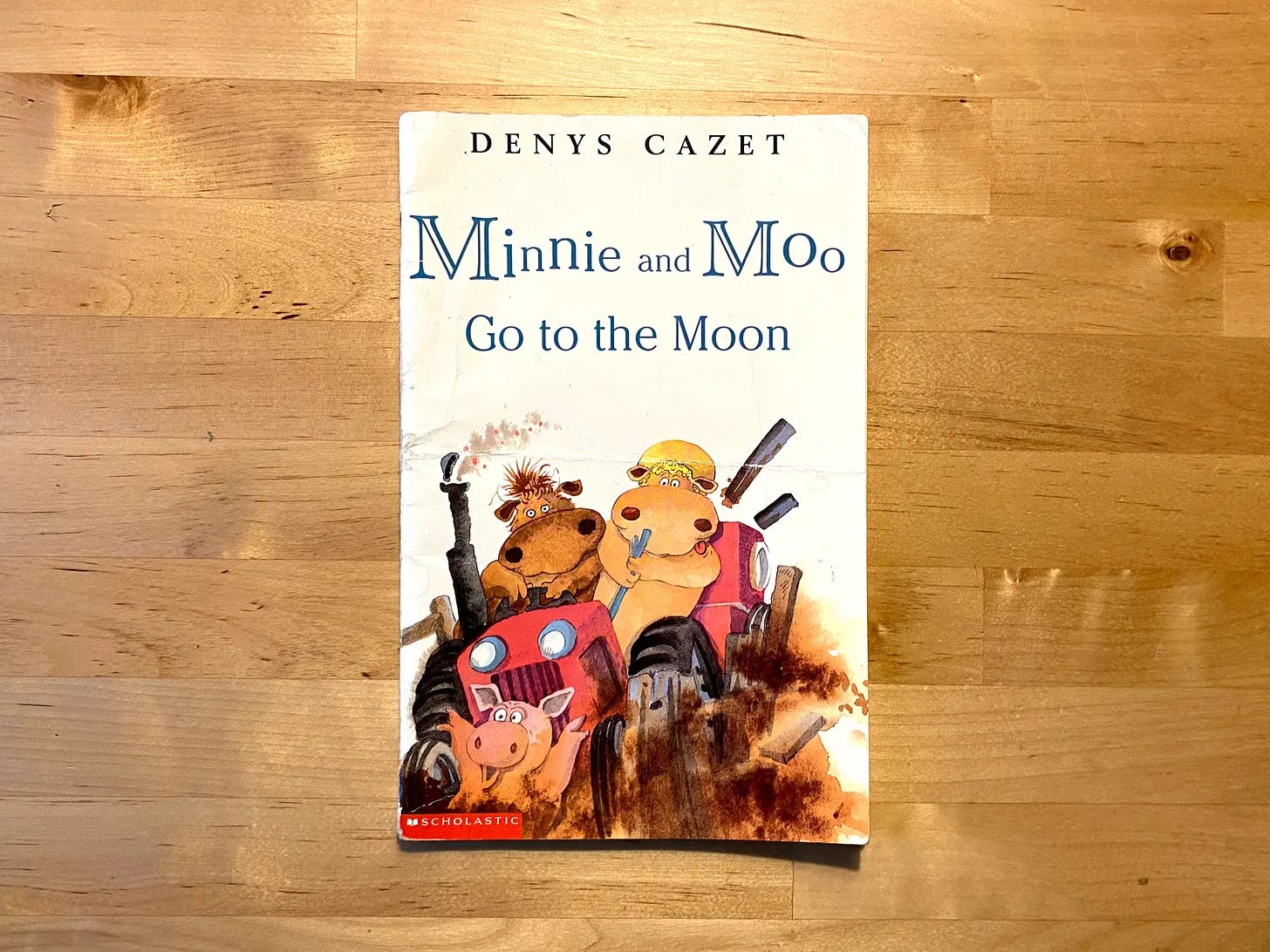

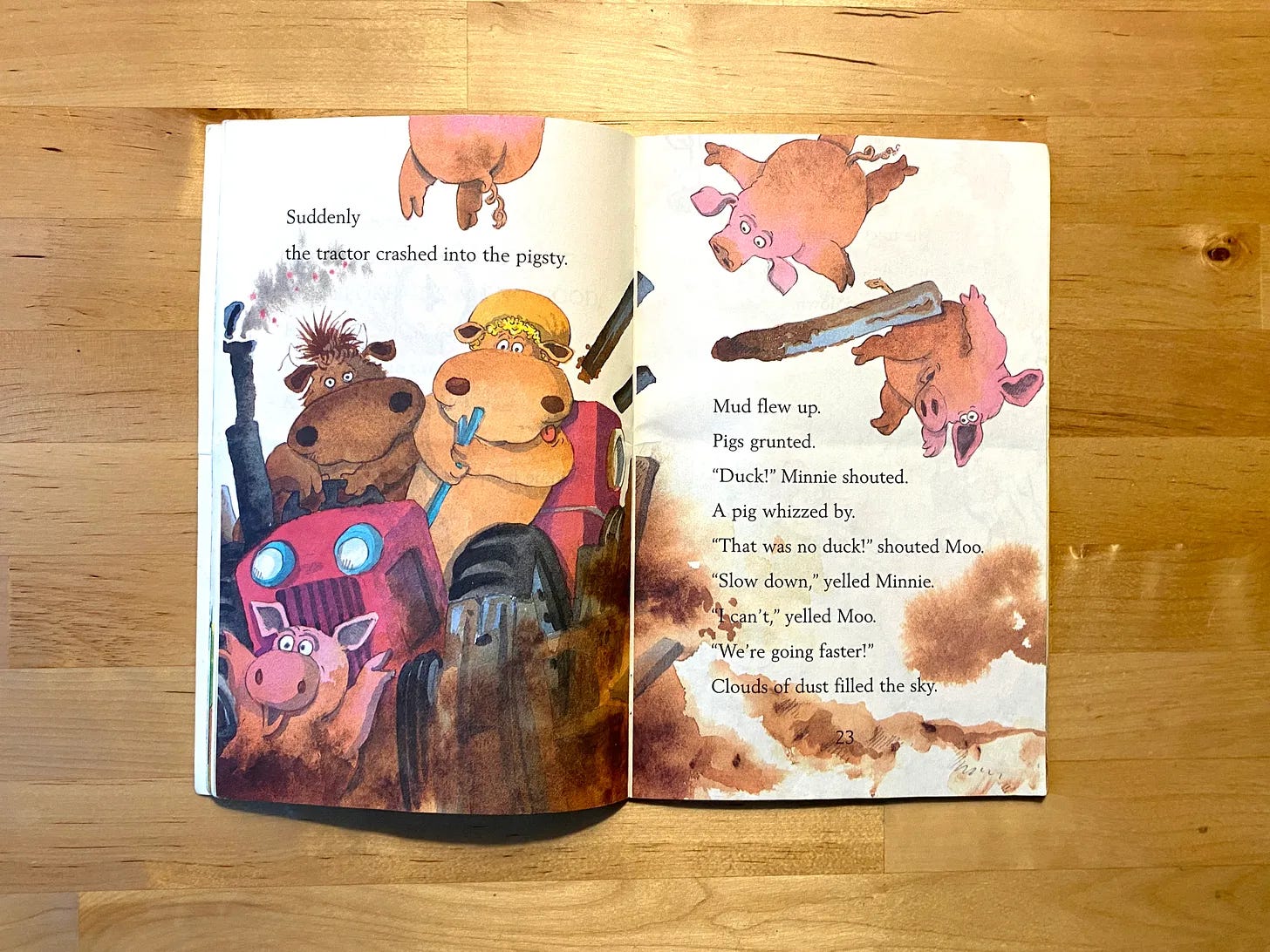

Minnie and Moo Go to the Moon (1998)

by Denys Cazet

Minnie and Moo is apparently a huge series with 16 installments, from 1998 to 2010, which is news to me! Now I want to get the whole collection to see if Cazet is a real consistent smarty-pants like I think he is. I learned that he was an elementary school teacher for 25 years, which explains the extremely good read-aloud quality this book has. I always assumed we owned this one, but my sister, whose memory is infinitely better than mine, told me it was a library book. She even said we used to race to see who could find it on the shelves first. I wish I could remember that, as it sounds adorable. The two main characters, Minnie and Moo, are cows that live on a farm together. They have a George and Martha look to them, on account of them being a pair of best friends with big snout-y noses and tiny expressive eyes. Similar to Frog and Toad, it's the classic “goofy roommates end up in an unfortunate, funny situation” vibe. Minnie and Moo decide they can probably drive the farmer’s tractor if they wear his hat and boots and say the magic words, “YOU CHEESY PIECE OF JUNK! YOU BROKEN-DOWN, NO-GOOD, RUSTY BUCKET OF BOLTS.” The tractor takes off, gets some air over a hill, making the cows believe they must have gone to space and landed on the moon. This book does what I call “idiot logic” really well, a la The Stupids. The back-and-forth dialogue in this one is very good, and I’d love to do a story in a similar vein. There's lots of room for jokes and antics, tons of pictures, and the chapters are the perfect length for a withering attention span.

Are You My Mother? (1960)

by P.D. Eastman

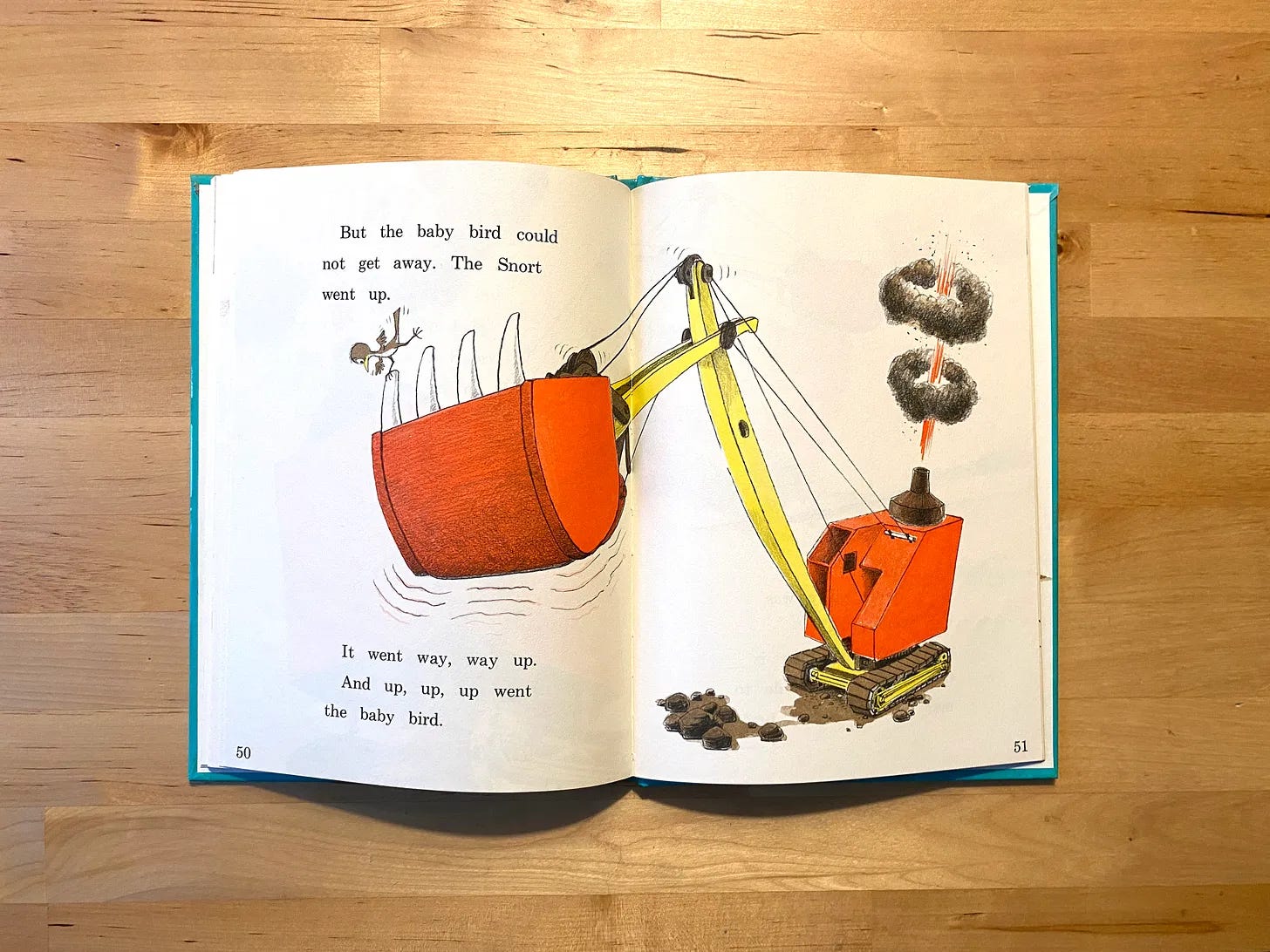

We owned this one, so it was in heavy rotation. It’s one of those repetition books about a baby bird looking for his mother, who he’s never met. He has no idea what she looks like, but he knows he definitely has one. This book is a little scary! I think that's what I like about it. It has an easy ending where he ends up back safe in his nest and his mother finally arrives, but not before questioning a freaky-looking kitten, a hen, a dog, and a cow (oops, three cow books). This is all pretty typical, but then he goes on to question an old car, a boat, an airplane, and a huge digger he calls a “Snort.” I felt so scared for the bird. He’s more clueless than you’d hope and the gigantic mechanical size of the Snort is really horrifying. Also, the cat, which has freaky staring eyes, says nothing while the other animals can talk, so it’s a threatening “I would really like to eat you” moment. In my mind, this is a super iconic story, and, as Jon Klassen has proved, questioning a series of weirdo animals is really entertaining and a great vehicle to fulfill and break expectations.

The Monster at the End of this Book (1971)

by Jon Stone and Michael Smollin

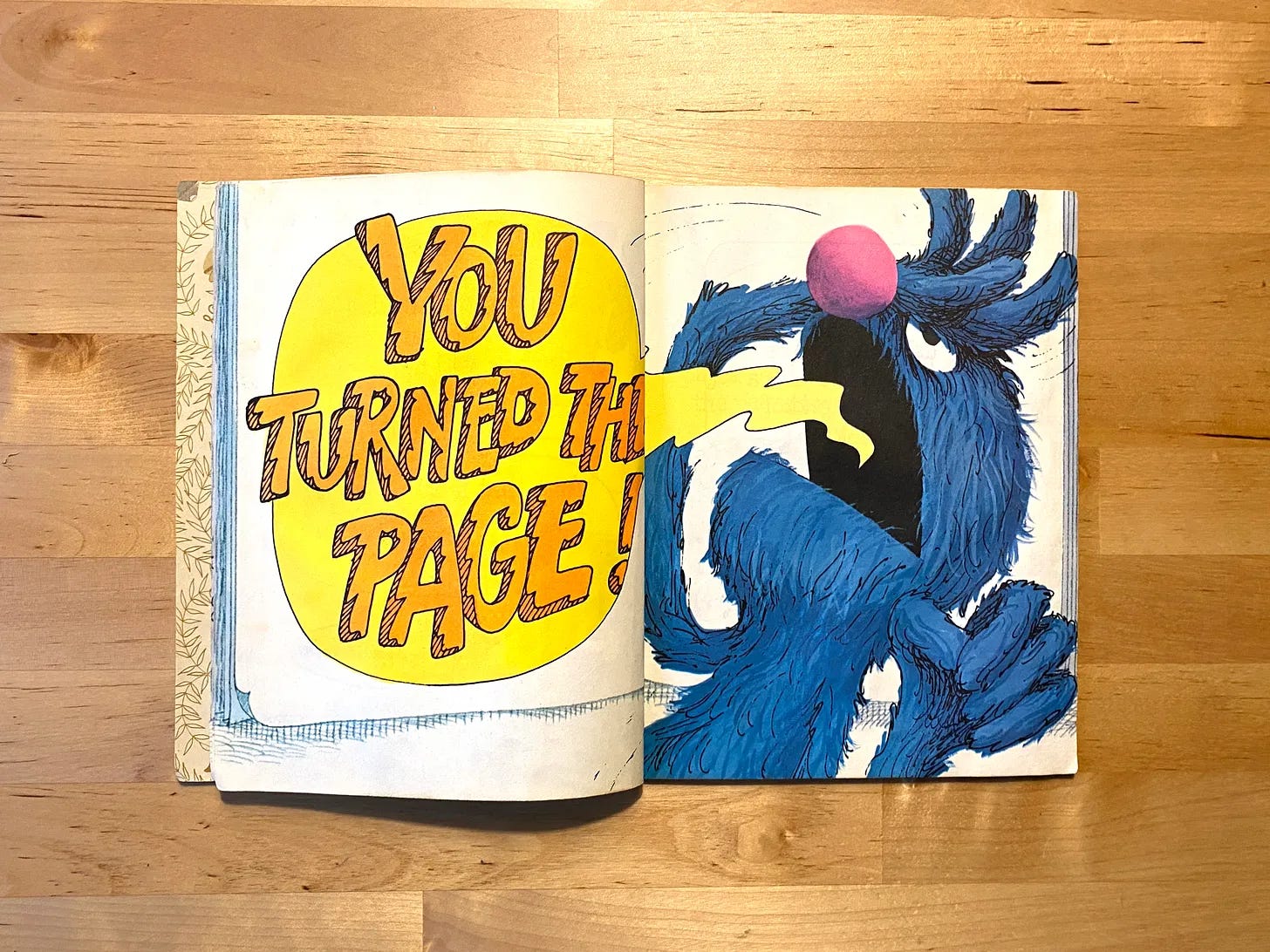

Thankfully, we also owned this one! We had a small pile of Little Golden Books, but this one, if you know it, obviously runs circles around them. It’s probably one of the best books ever made and maybe THE best read-aloud, especially if you’ve got my mom to read it to you. This one requires some volume, so you gotta be prepared to yell the yelling parts for full impact. In case you, for some reason, have never read it before, the book is a glorious symphony of huge lettering, speech bubbles, chaos, and Grover becoming increasingly desperate for the reader to STOP TURNING PAGES unless we meet the horrible monster at the end of the book. After turning pages tied off by rope, boarded up with wood, and stacked high with bricks, Grover discovers the monster at the end of the book was him the whole time. Kids are tested by Grover’s pleas to stop reading, and if my reaction was any indication as to the kind of person I am, I loved turning the page to destroy his barricades. What does that say about me? It’s so interesting how eager kids probably were to laugh at his fear, or maybe a lot of them were scared along with him, begging their parents to stop turning. I have a book coming out next year about a bear that is absolutely my attempt to rip off even a sliver of the genius of this one, so it’s no surprise that it’s on my list. Books where the character is talking directly to the reader like they exist in the same world are crazy.

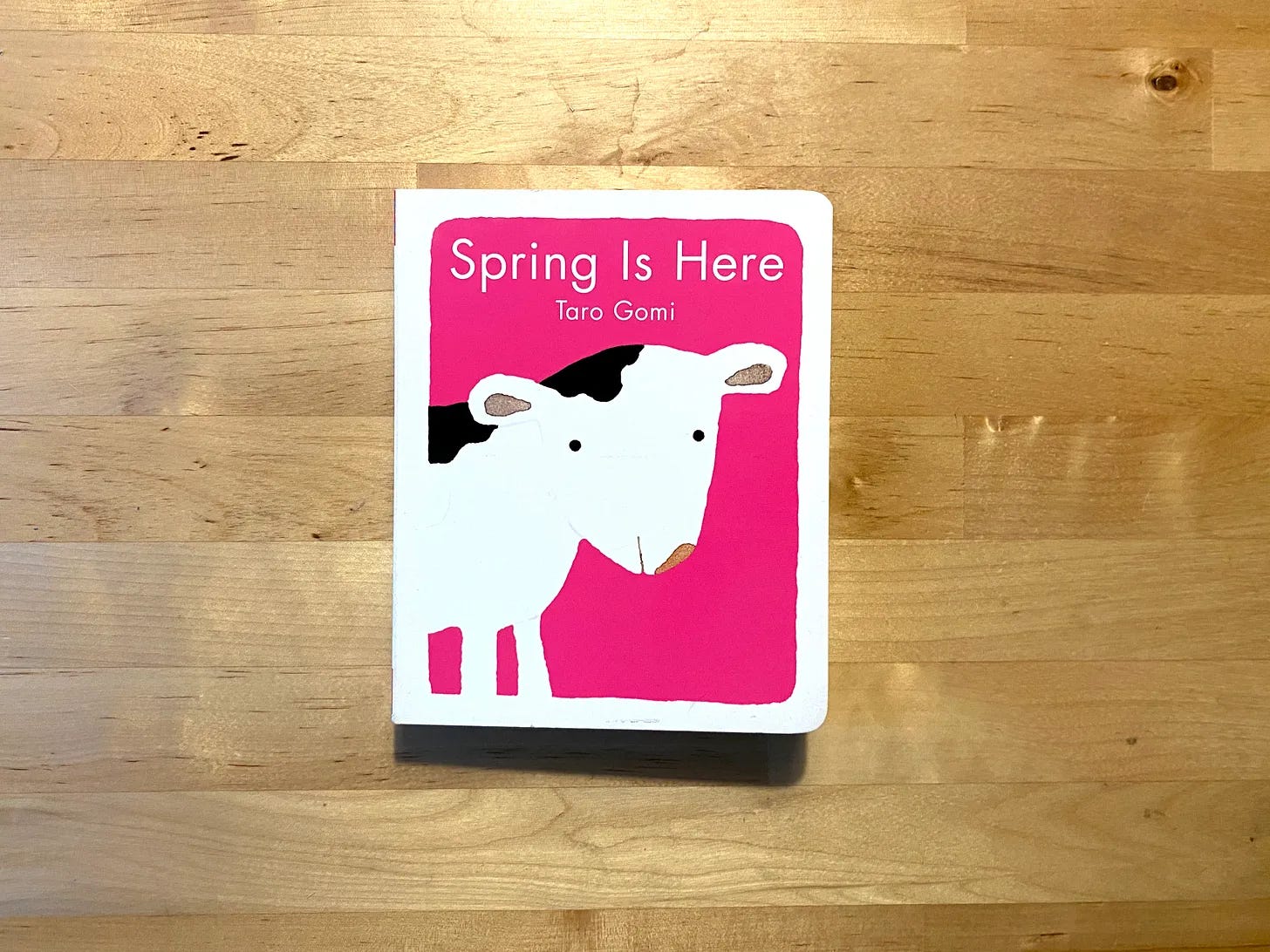

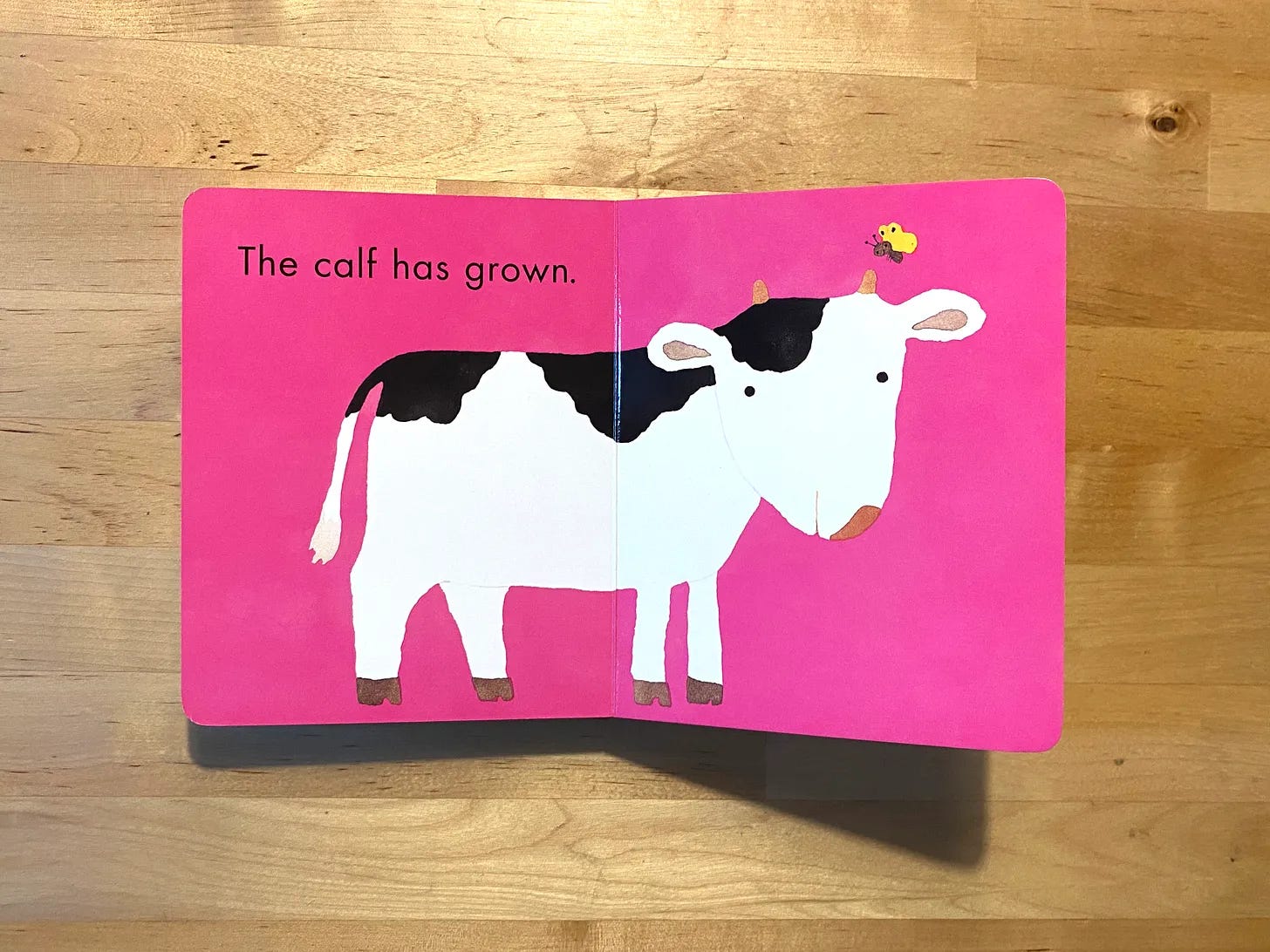

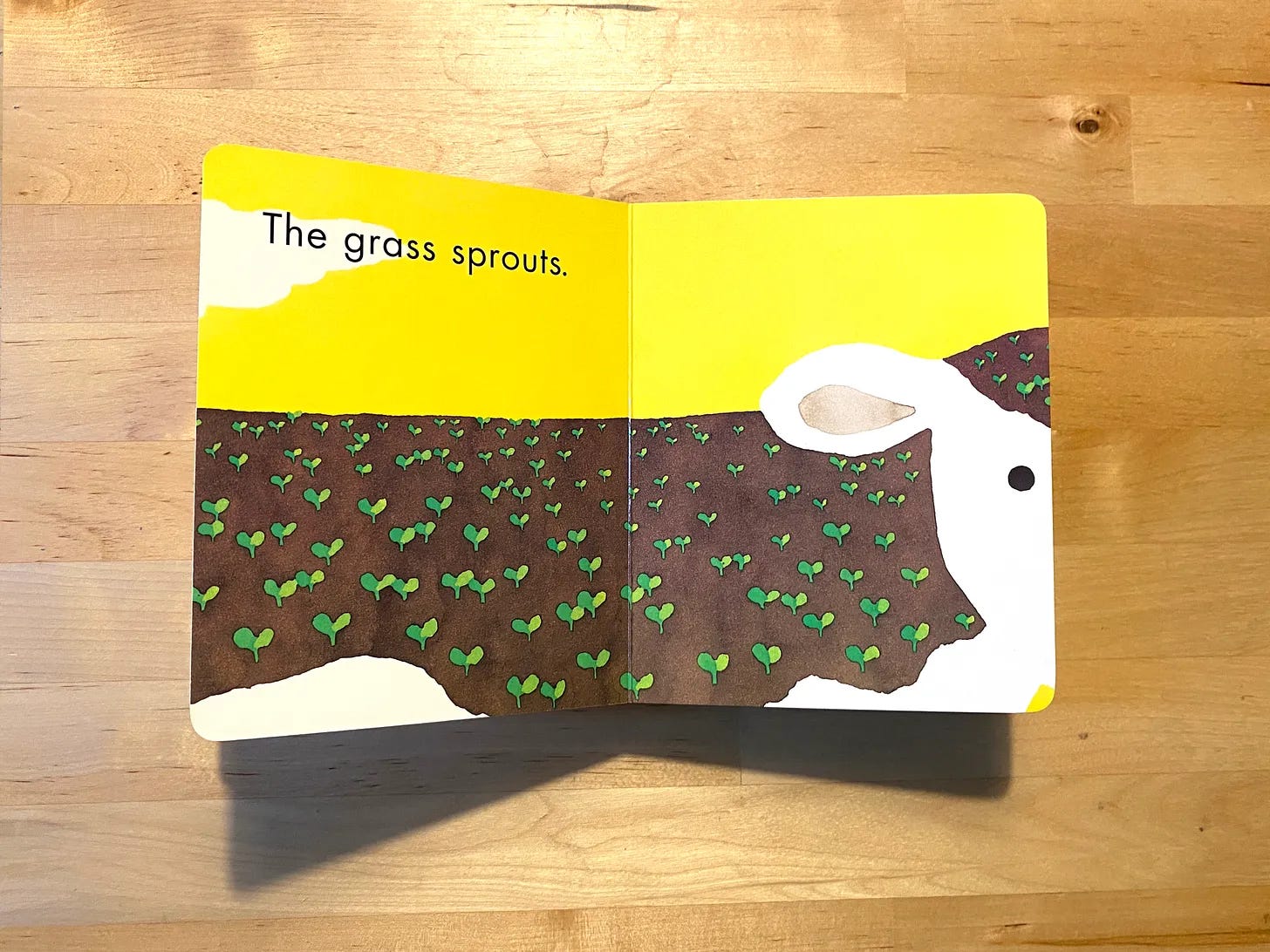

Spring is Here (1989)

by Taro Gomi

Before I had accepted that I was supposed to make picture books, back when I thought it was editorial illustrating or bust, I loved looking at board books. They are infinitely satisfying little objects, and their simplicity and mass are delicious. I found out about Taro Gomi when I saw his board book series about a little truck, plane, and boat, respectively, at a bookstore while I was still in art school. I couldn’t totally figure out why I was so engrossed with something for babies.

Later, I would look back and be like, “Oh, duh of course, they’re spectacular, you idiot.” I can highly recommend all of his board books and pretty much everything else he’s ever done. This is one that has very obviously influenced my art style, too, I think. Spring is Here might be one you’ve heard of before, but if not, I’m thrilled to tell you about it. It starts with a little calf who is slowly growing its black spots, and we zoom in toward its back. The spot transforms into fresh dirt, which sprouts grass, and then a huge field with children running through it. The seasons change, the grass turns brown, and the snow falls. It melts, we zoom out, and the calf has grown up into a cow. Already, it’s a beautiful, simple little story that could easily be a wonderful short animated film or something, but paired with Gomi’s perfect simple art style, it’s a tiny work of art. Imagine being a baby with such a masterpiece to chew on and drool all over. I have GOT to make some board books, it’s like the ultimate art form to me. Gomi makes me feel validated in my pursuit for the smartest, simplest artwork featuring little guys and bright, weird colors.

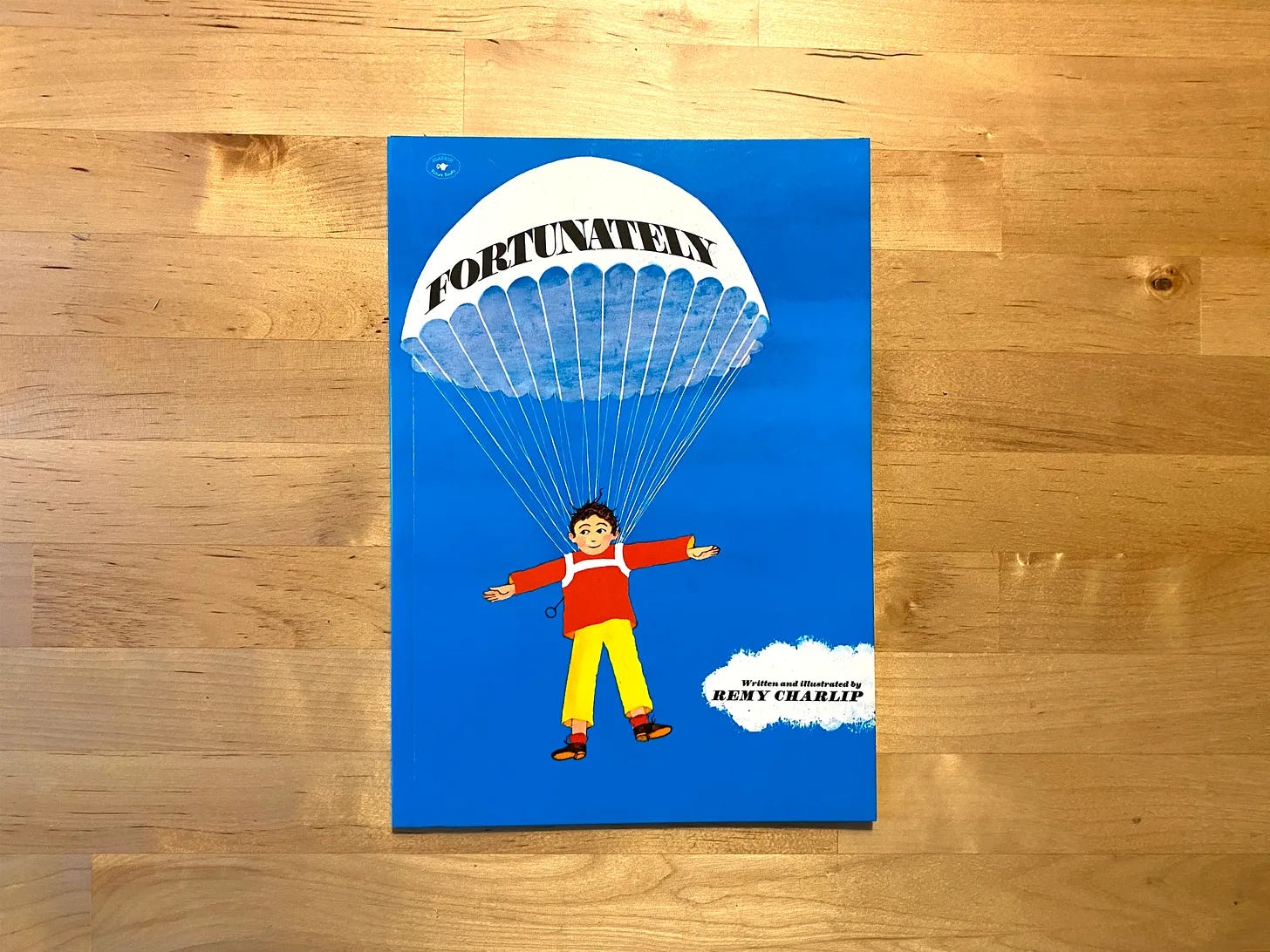

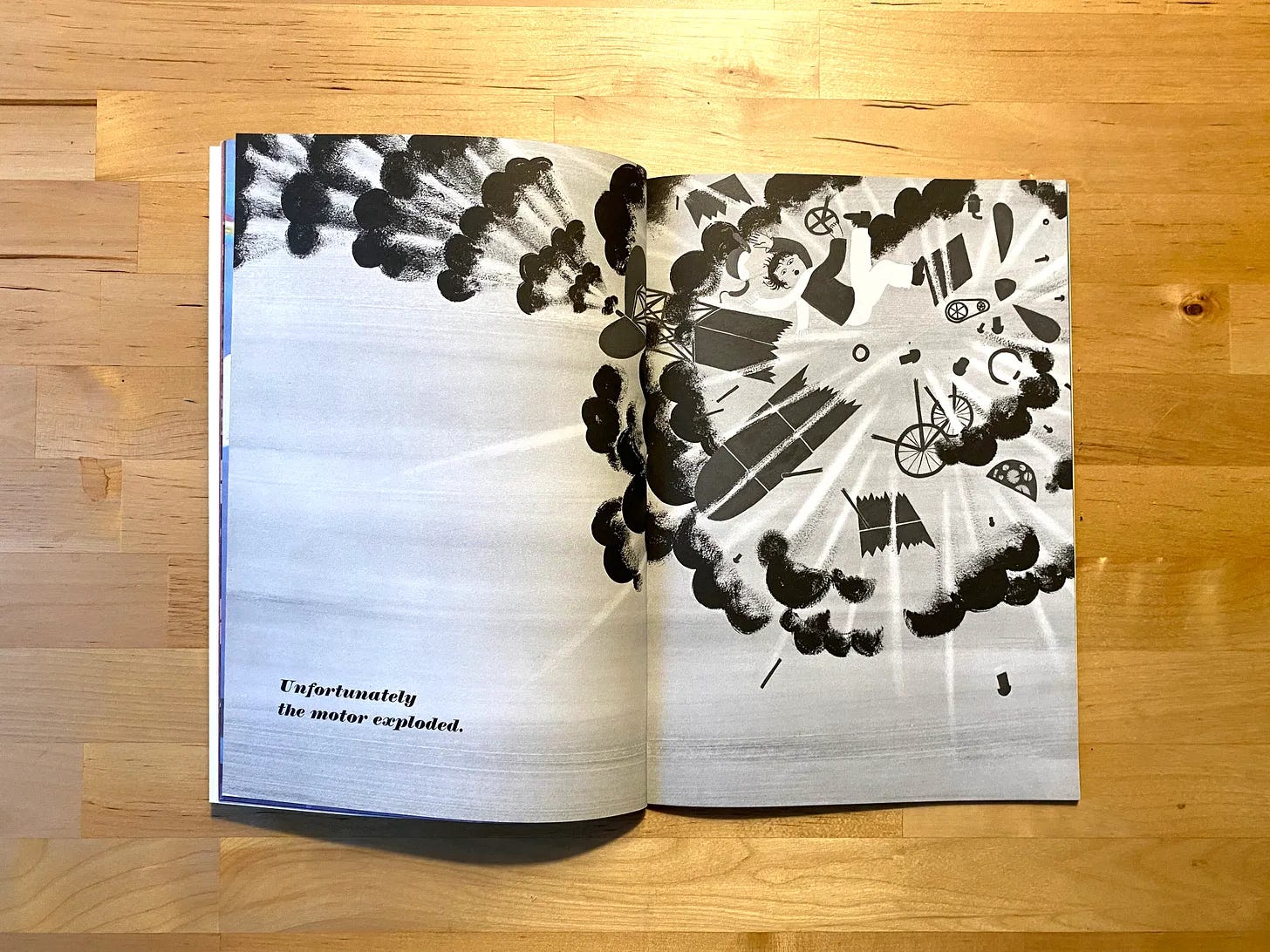

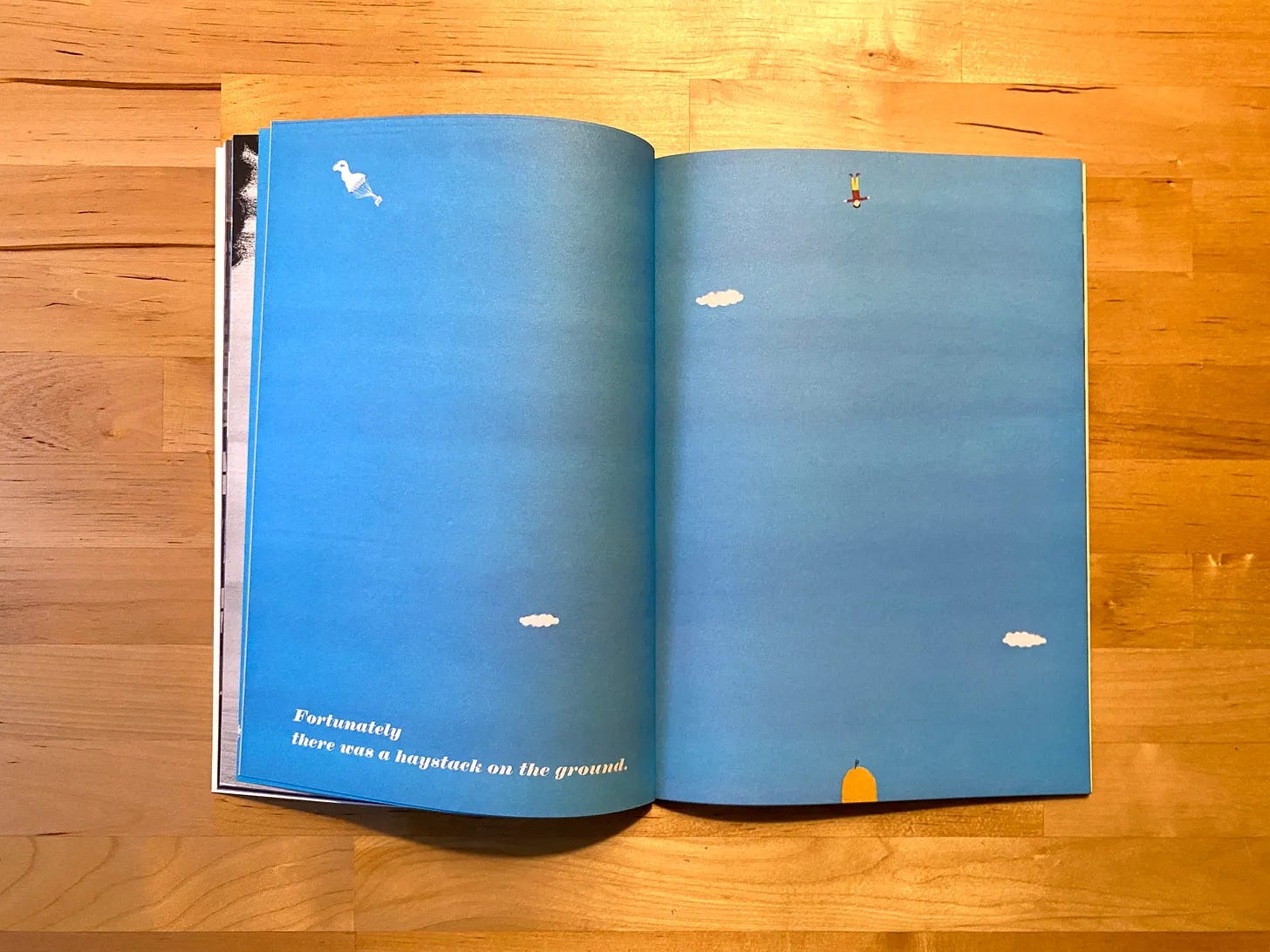

Fortunately (1964)

by Remy Charlip

Remy is another genius writer I found out about in art school, shown to us by our infinitely insightful teacher and prolific artist, Pete Ryan. It’s a masterclass in both composing an image in extreme opposites and in using dramatic story twists, the artwork emphasized by the use of black and white next to color. In Fortunately (a word I cannot spell for the life of me), we follow Ned, who gets a letter about a surprise party he’s been invited to, but unfortunately, he lives in New York, and the party is in Florida. Fortunately, his friend loans him an airplane! Unfortunately, the motor explodes in midair. The pattern of great luck to horrible misfortune continues for the whole book, and it’s such a blast to guess what horrible thing will happen next once you get the formula. The escalation! This is another perfect picture book, but we can expect that from anything with Remy Charlip’s name on it. The compositions are all such heavy hitters. I feel smarter every time I look at it.