This newsletter may be “too long for email,” meaning it may appear clipped or truncated in your email inbox. If you see three gray dots, click them to read the full email.

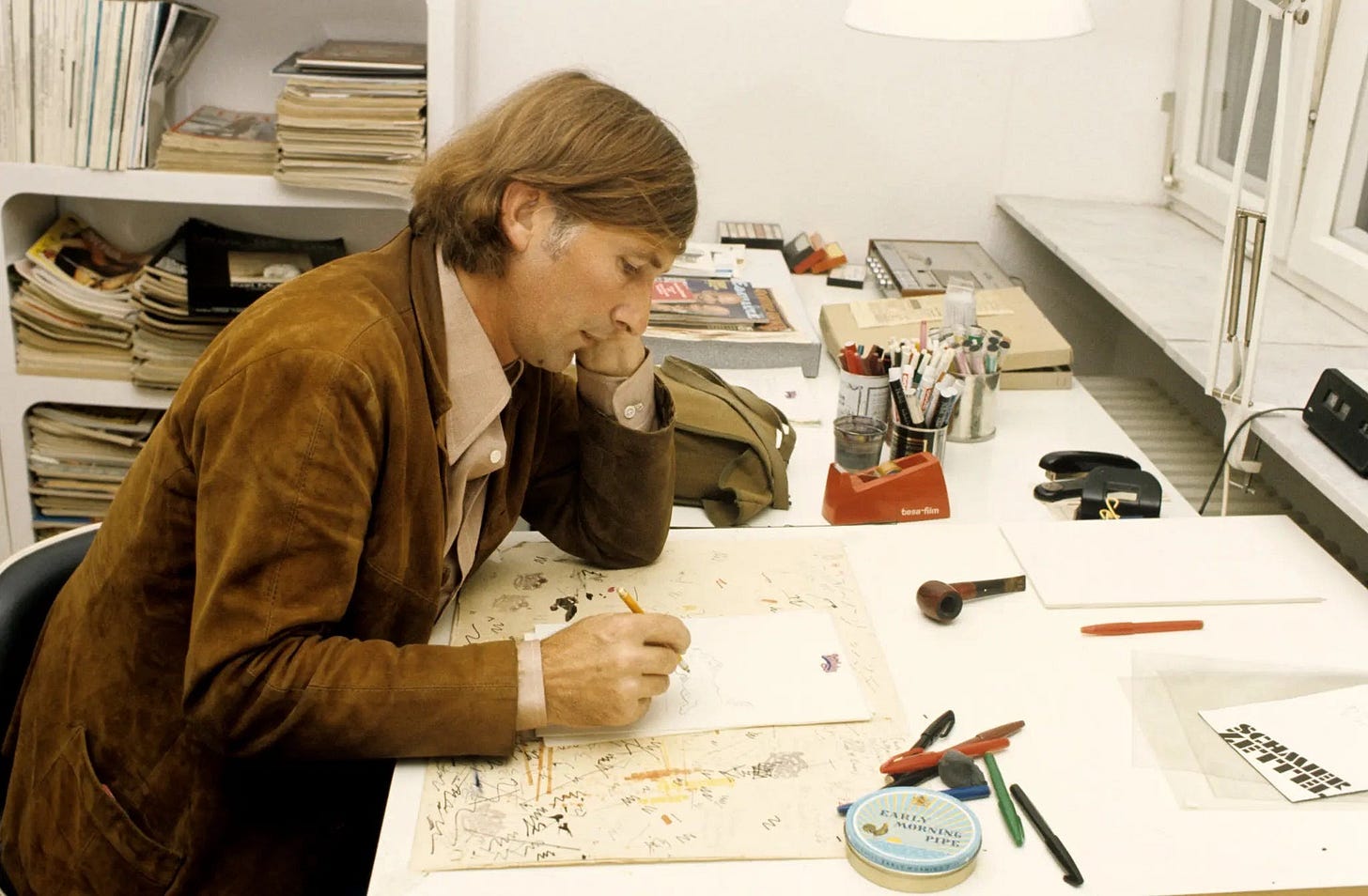

Writing an article about Tomi Ungerer that focuses on definitions is ironic, considering that Ungerer was an idiosyncratic artist who radically defied definition. He frequently experimented in art and in life, rejecting the limitations of form and expectations. To classify Ungerer in any definite terms feels reductive. And yet, when I read his books, I think of one word: sensual. It’s a word he himself uses to explain his artistic style. But the word—much like Ungerer—is not without nuance, misinterpretation, and irony. And as much as Ungerer indulged in the gratification of the senses, he also understood violence and destabilization. His experiences growing up in Strasbourg during the horrors of World War II under the Nazi occupation profoundly influenced him. Scenes of terror, anxiety, bloodshed, and debauchery are not only in his political anti-war posters; they’re also in his books for children.

While Ungerer may have had a proclivity to shock and awe, he also believed in the power of poetry.

“Always for children, never use a word tree, bird, or flower. Say this is a daisy; this is a forget-me-not. Isn’t that lovely? A forget-me-not…Every word is a poem. Every word is part of a possible poem.” — Tomi Ungerer, on writing for children.

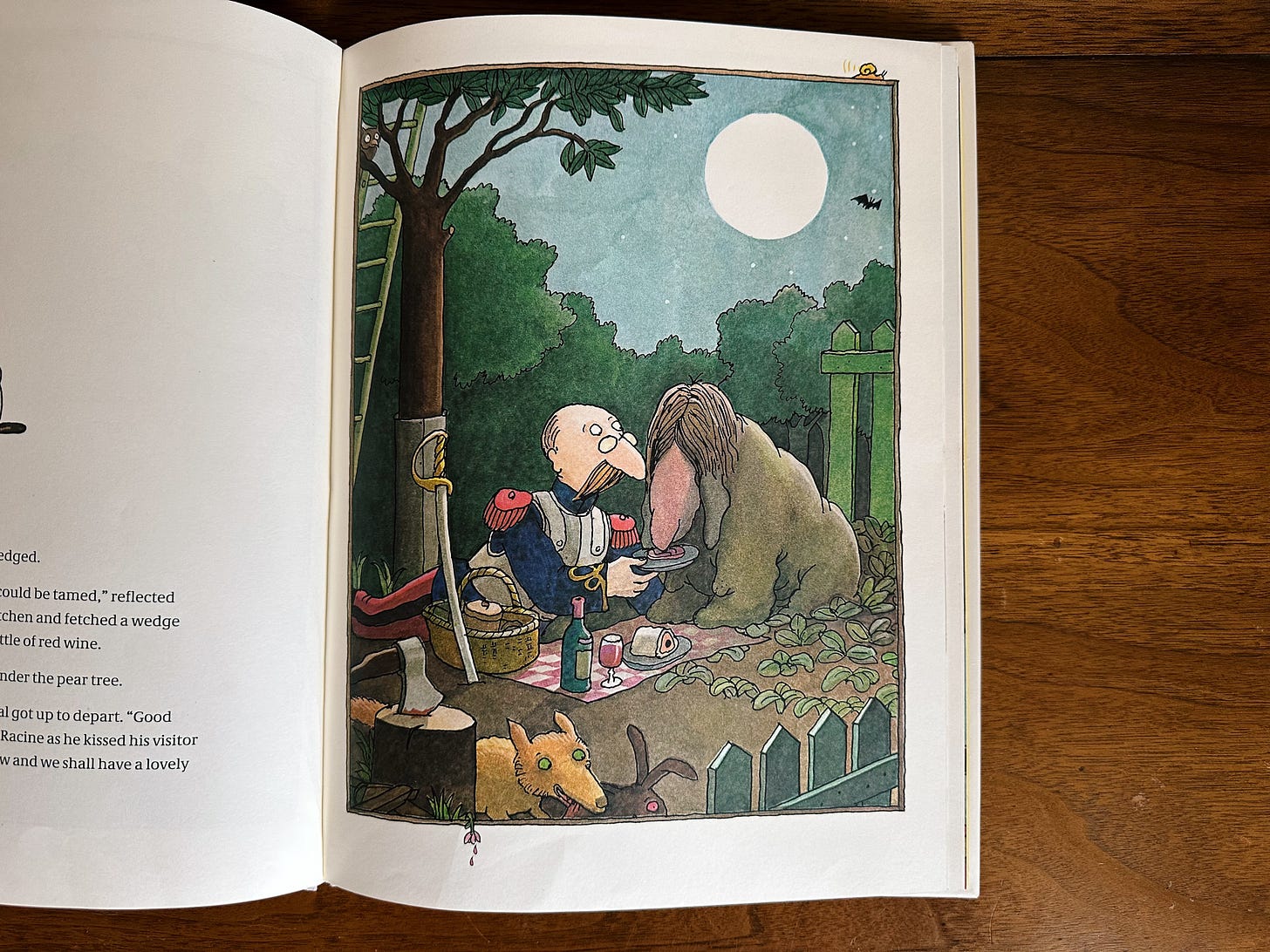

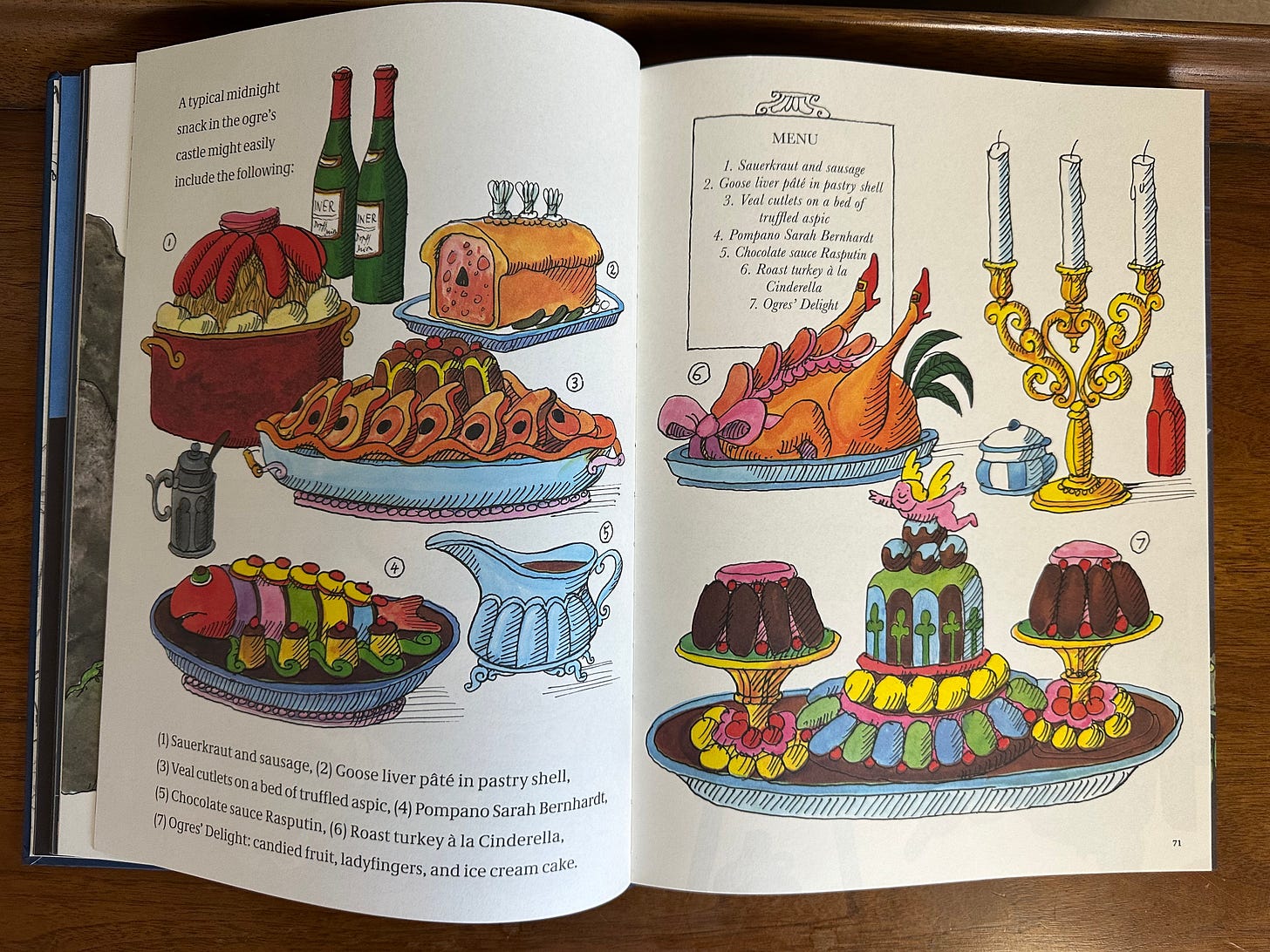

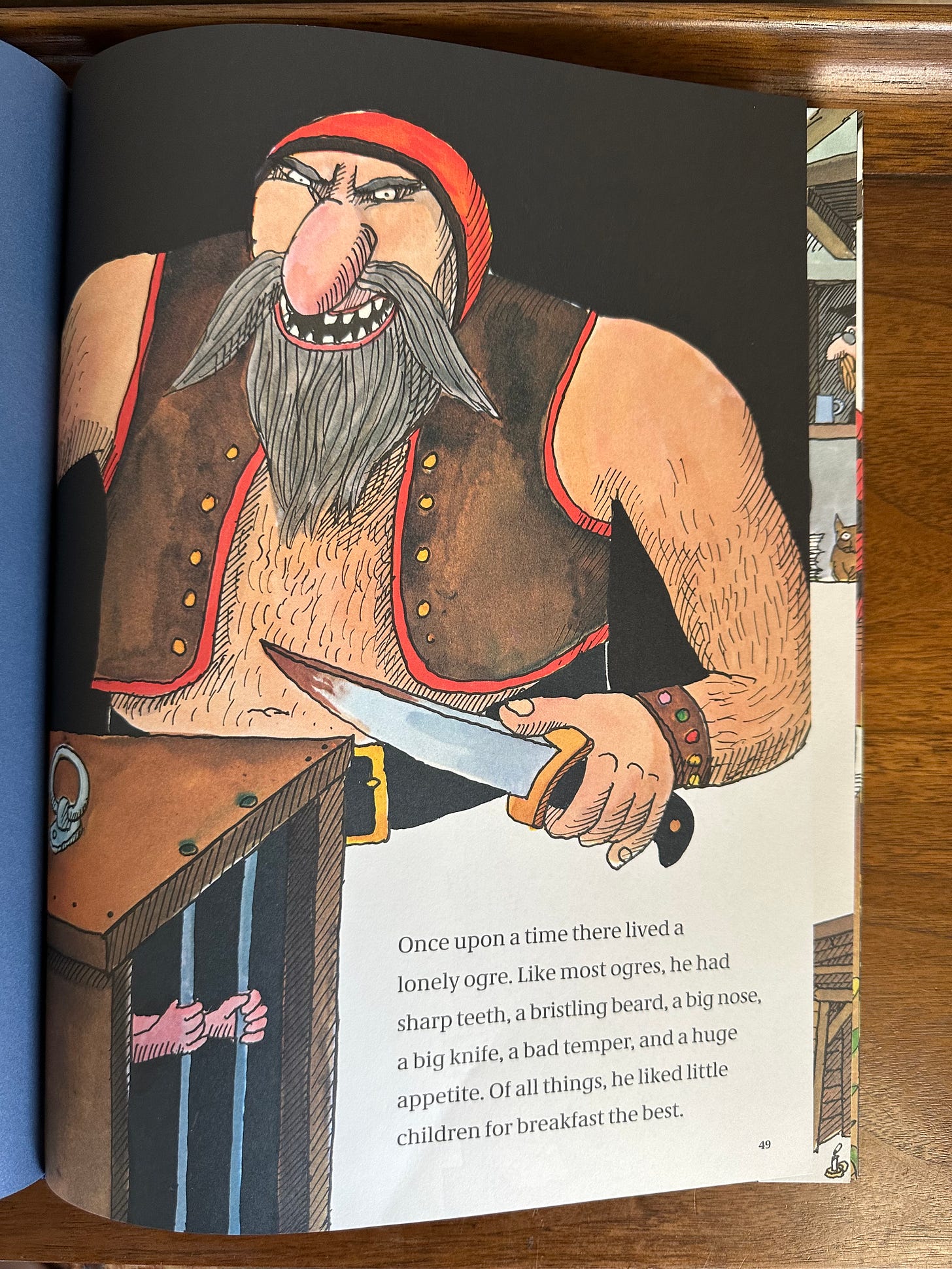

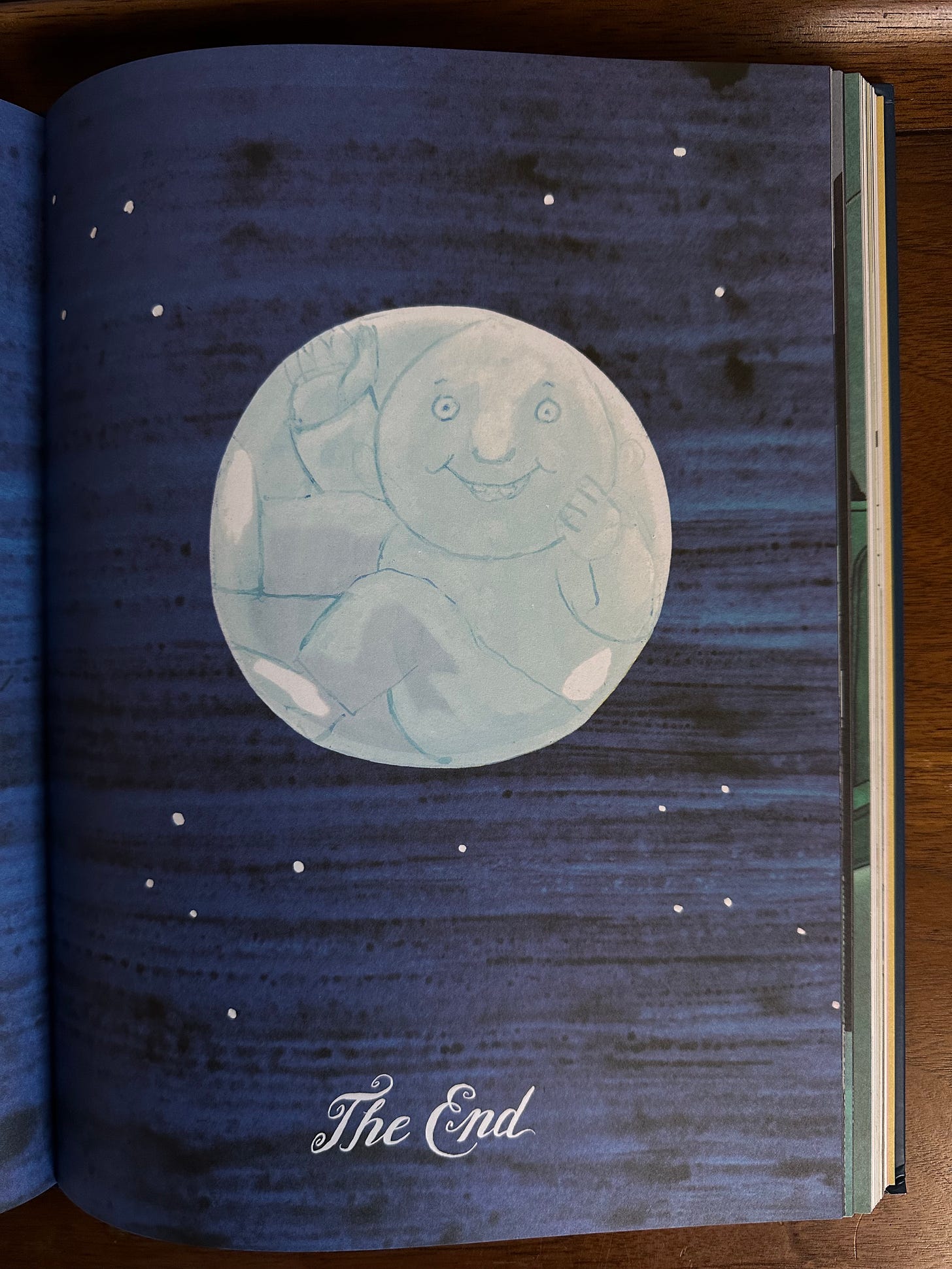

His worlds contain many poetic contrasts: humor mingles with fear, satire fuels eroticism, beauty is found in the unexpected—the delight of his stories exists within these tensions. You can feel the energy of his ravenous curiosity, his zest for life! Even when his protagonists face harrowing situations, they’re never afraid. Instead, they lean on their playful ingenuity. In stories such as Moon Man (1967), Zeralda’s Ogre (1967), Flix (1997), and Emille (1960), the main characters are outsiders, but because of their unique talents (and a bit of luck), they become heroes. But Ungerer isn’t one to let them revel in their glory; instead, he has them happily return to their outsider existences. The goal isn’t for these misfits to gain acceptance (although that’s usually a happy side effect) but to help others in need.

I have an idea for a book about hunger or thirst, but I haven’t got the ending. There is another children’s book I still want to do. It’ll be just for the poetry, for the atmosphere. I love the fog, and I love the full moon, so I’d like to make a book on that. My books don’t always need to be engagé, aggressive, with a lot of detail. I also like simple books that are just for dreaming.

— Tomi Ungerer, on Fog Island for Apartamento Magazine

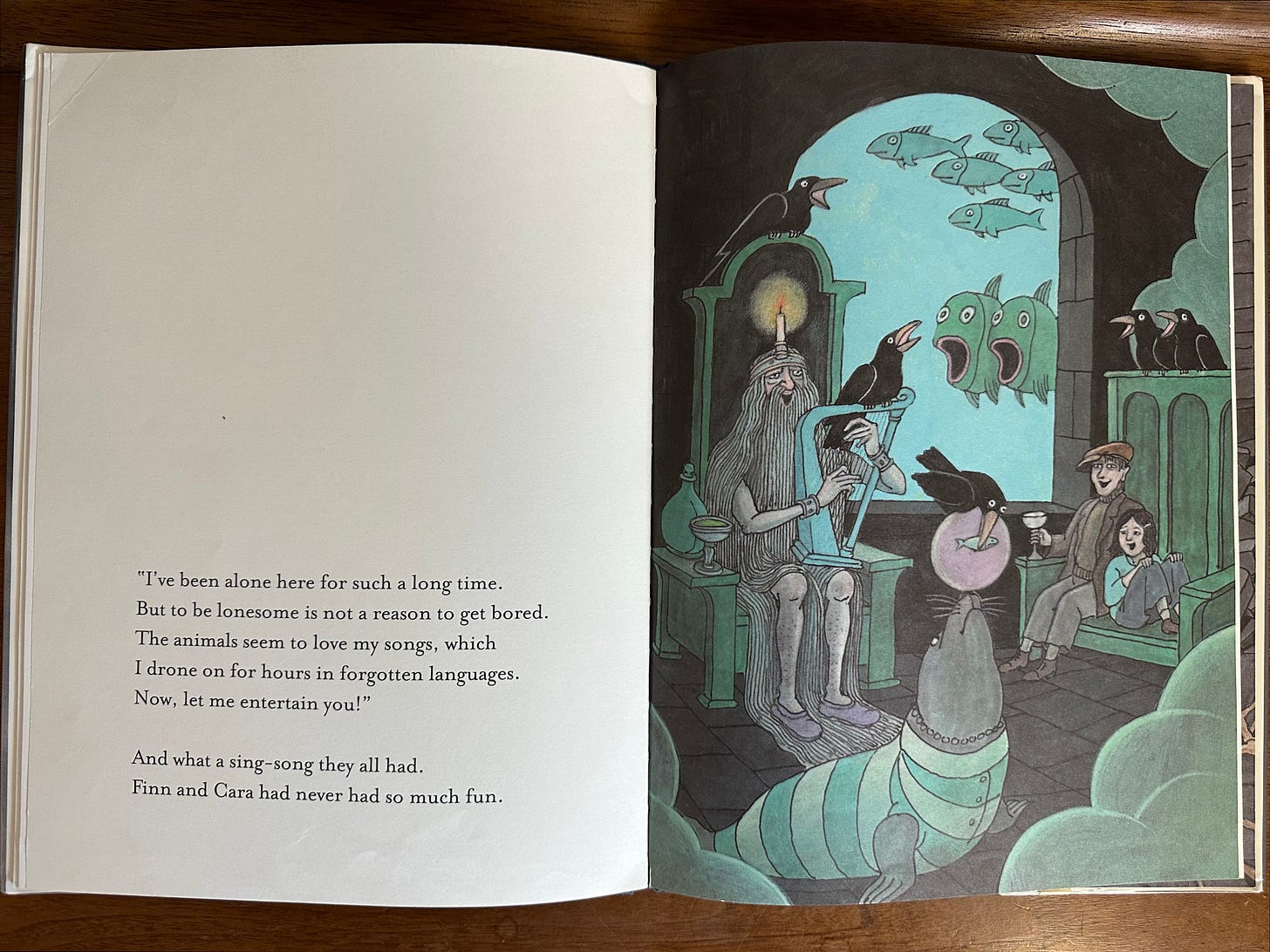

In one of his most poetic books, Fog Island (2012), Ungerer uses atmosphere and sensory detail to evoke an eerily captivating story. Ghostly tones of gray and black fill the open landscapes; as if a thick fog has enveloped the book. The text is equally sensuous:

“The steps were steep and slippery and in the moonlight, everything seemed to be dusted with flour. They climbed and climbed and climbed…At last they reached a door set into a high stone wall. They rang the bell and the door opened slowly, squeaking on its rusty hinges. There stood a wizened old man.”

In this misty folkloric tale, two adventurous young siblings, Finn and Cara, are swept out to sea to the mysterious—and possibly deadly—Fog Island. While ashore, they meet the surprisingly friendly and extremely hairy Fog Man, an ancient islander who shows them how he creates the fog and offers them warm bowls of soup along with plenty of evening gaiety. However, when they wake up in a shelter of ruins, the Fog Man is nowhere in sight. Had it all been a dream? Eventually, they make it home safely, but no one believes their story. Then Cara finds a long piece of hair in her soup, and she and Finn smile knowingly—it was real! Thrillingly, both the children in the story and the children reading the story are in on the secret.

This is Ungerer’s gift: the ability to turn everything into a sensorial experience. Reading his books makes you feel things, but those feelings aren’t always pleasurable. For many, Ungerer is too much: too violent, too gratuitous. This was especially true in the 1970s when puritanical American (and British) librarians discovered Ungerer’s adult erotica artwork and banned his books from libraries for over a decade. Those who were concerned with the propriety and correctness of children’s books saw him as a threat. Like the characters of his children’s books, Ungerer was an outcast. However not in Europe. There he was revered not only for his books, but for his work in advertising, his satirical and political drawings, and his humanitarian efforts. But America considered Ungerer “erotically incorrect”. Anyone with the audacity to draw mechanical penises, women in bondage, and frogs practicing Kama Sutra did not belong in children’s publishing. After being shunned from the States, he moved to Nova Scotia and eventually to Cork, Ireland, where he remained until his death in 2019.

Ungerer was a provocateur. He was galvanic. He wanted to stir things up and turn you on. And why wouldn’t a sensationalist be interested in sex? Sex is an artistic language, and Ungerer’s interpretation was radical. He was a part of the sexual revolution of the ‘60s and ‘70s. His views on sexuality, sexual fantasies, and the rights of sex workers were highly progressive for the time. But what many get wrong is they think Ungerer fetishized and objectified women when actually he empowered them. When his book Erotoscope was published by Taschen in 2002, there were more women at the book signing than men. The reality is most of us are interested in sex: we’re human—and Ungerer’s art is viscerally humanistic.

The synonyms of the word sensual are carnal, fleshy, sensuous, and animal. These words also describe much of Ungerer’s work, the sheer deliciousness of his style (a phrase Maurice Sendak used when referring to James Marshall, but the same can be said of Ungerer). But if you search “sensual children’s books” on Google, nothing comes up; instead, you’ll find something like “10 Children’s Books with Uncomfortably Sexy Titles.” Sensuality is sometimes mixed up with sexualization, and of course, the two can intertwine, but they’re different. The word is misunderstood—which is why it’s fitting for a man as complex as Tomi Ungerer.

SENSUAL

: relating to or consisting in the gratification of the senses or the indulgence of appetite

FLESHY

: having a sensuous quality

: marked by abundant flesh

a. Corporal, bodily

b. of, relating to, or characterized by the indulgence of bodily appetites

SYNONYMS: CARNAL, FLESHLY, SENSUAL, ANIMAL

LASCIVIOUS: filled with or showing sexual desire

SENSES: of or relating to sensation or to the senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch

a: devoted to or preoccupied with the senses or appetites

VOLUPTUOUS

: suggesting sensual pleasure by fullness and beauty of form

“Unspeakable acts were performed.” — The Beast of Monsieur Racine

LUXURIOUS: suggests the indulgence of sensuous pleasure inducing bodily ease and languor

FEAR

: an unpleasant often strong emotion caused by anticipation or awareness of danger

: arousal—a heightened state of adrenaline

: a state of physiological and psychological excitation caused by sexual contact or other erotic stimulation

“Once upon a time were three fierce robbers. They went about hidden under large black capes and tall black hats.” — The Three Robbers

THE NIGHT

: the time from dusk to dawn when no sunlight is visible

: an evening set aside for a particular purpose

: absence of moral values

“Badoglio and his bride danced in rapture all evening. At midnight they left—singing in the moonlight—for a honeymoon in Sadrinia.” — The Hat

Moon

: the earth's natural satellite — that shines by the sun's reflected light

: something impossible or inaccessible

: idle reverie—to daydream

MOON AFTER: to spend too much time thinking about or looking at (someone or something that one admires or wants very much)

“Having satisfied his curiosity, the Moon Man never returned to earth and remained ever after curled up in his shimmering seat in space.” — Moon Man

Bonus recommendation: Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne by prizewinning children's book author and scholar Katherine Rundell. A dazzling modern biography of John Donne: the poet of love, sex, and death during the Renaissance period. It’s one of my favorite reads of the year so far. (It’s not a children’s book.)

Interested in buying Tomi Ungerer’s books? Check out the Moonbow Bookshop page. Purchasing through my Bookshop is an easy way to support Moonbow while simultaneously supporting independent bookshops.

Thank you, Rachel! I’m happy you enjoyed it!

This is an amazing post! I’ve been really craving some big picture looks at children’s books creators I admire and you did such a great job with this one about ungerer (one of my favorites). Loved it!