Moonbow is a reader-supported publication. It exists because of the support of generous readers like you! If you enjoy Moonbow, the best ways you can support it is to subscribe, share this newsletter with a friend, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

This is my last Moonbow newsletter of the year. I’ll be back in January. Happy holidays!

The Fantastic Imagination of Jim Henson

In Brian Jay Jones’s biography of Jim Henson, Frank Oz —famous puppeteer and Henson’s closest collaborator—described the Henson brand as “affectionate anarchy”. He believes that the success of The Muppet characters comes from their ability to be safe and loving while simultaneously being chaotic and wild. It’s this strange, delightful dichotomy that continually draws me to Henson’s characters but also to stories, especially fairy tales. Fairy tales are ripe with paradoxes, the most obvious being Good and Evil, but also Truth and Lies, Punishment and Reward, Ugly and Beautiful, Light and Dark, Fantasy and Realism. The modern appeal of fairy tales often stems from their charming, whimsical elements, but the original stories are dark and brutal. Someone is burned alive, someone’s toe is chopped off, or someone is eaten—which brings me back to Henson, whose motto for The Muppets was: “It all ends in one of two ways: either someone gets eaten or something blows up.”

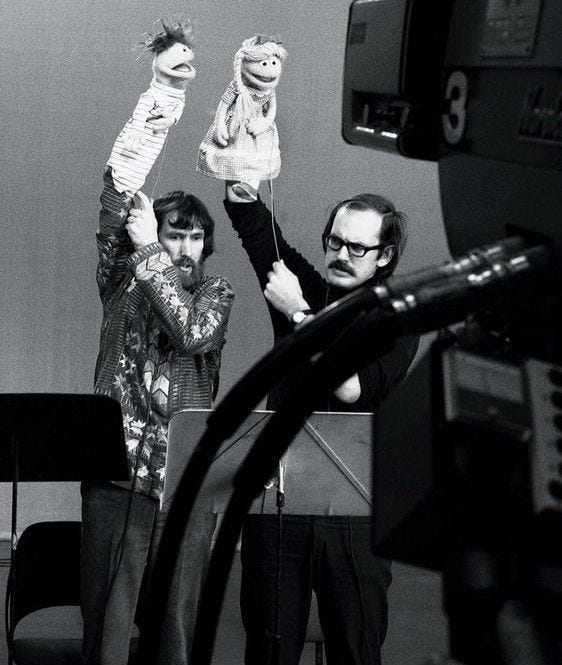

Jim Henson and Frank Oz

Like fairy tales, many of Henson’s stories were short and compact. They’re an exaggerated distillation of the real world. Most of the time, we’re not privy to the inner life of a Muppet character. Instead, we create meaning from their externalized words and actions. In a 2018 interview with The New Yorker Radio Hour, Frank Oz talked about the Muppet character Animal, “There’s no way in God’s earth that Freud could penetrate Animal. There’s no psychology whatsoever in Animal; there’s just sensuous and appetite and desire.” He goes on to describe Animal in five words: drums, food, sleep, sex, and pain. “None of this is known to the public,” he adds. These descriptive words help Oz believably portray Animal, but audiences likely have their own words to describe him. The same can be said of the characters in fairy tales. And because we know little about these characters’ psyches and because of the ever-present paradoxical psychological motifs, we’re able to see parts of our own psyches: Good and Evil, Affectionate and Anarchic.

But it’s not all under the surface; Henson clearly loved fairy tales, folk tales, and children’s stories, and he recreated them from as early as college up until his tragic death in 1990. The most recognizable being Tales from Muppetland, Sesame Street’s “News Flash” segment, and his last film, The Labyrinth (1986)—the ultimate mashup of many of his favorite tales.

In this special edition of “5 Things,” I’m going to break up Henson’s career into five sections and share many fairy tale connections. This is a detailed list, so take your time with it. Read it slowly over the holidays with a cup of spiked egg nog. And if this isn’t something you’re interested in, that’s OK. This is for the lovers, the dreamers, and me.

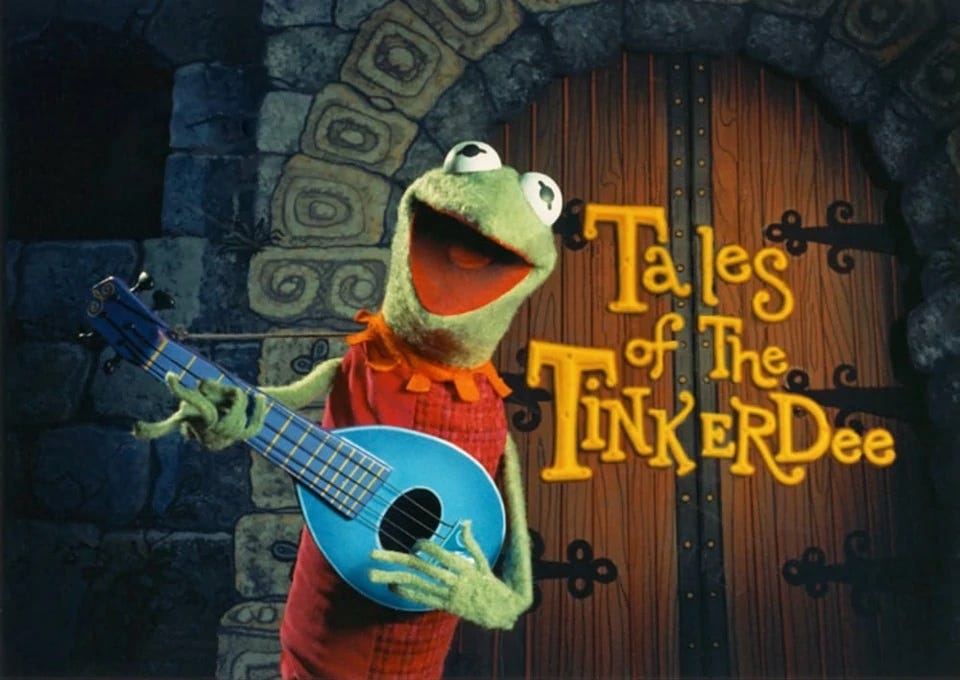

The Tale of the Tinkerdee

Even as early as his first year of college, Jim was interested in using puppets to tell fairy tales. In his puppetry class at The University of Maryland, Jim created a production of one of his favorite books, James Thurber’s modern fairy tale The 13 Clocks (1950). After discovering this, I immediately recognized the parallels between Thurber’s and Henson’s work. The 13 Clocks is a peculiar, genre-bending mix of fantasy, fairy tale, parable, and poetry. Neil Gaiman, who wrote the introduction for the New York Review of Books 2018 reprint, claims it’s “probably the best book in the world” and compares it to William Goldman’s The Princess Bride (1973) and William Steig’s Shrek (1990). It also reminds me a little of the Rocky and Bullwinkle Fractured Fairy Tales (1959-1964). It’s wonderfully written and delightfully funny—especially when read out loud. There’s a famous line in the story by an odd, enigmatic man named Golux who tells Prince Zorn, “I make mistakes, but I am on the side of Good,” which could have easily been the words of Jim Henson.

The 13 Clocks, illustrated by Marc Simont (1950)

Like Thurber’s story, Henson’s fairy tale mashups are relatable, quirky, and fun. After college, Henson wanted to create a more significant production of The 13 Clocks, but instead, in 1962, Henson and Jerry Juhl shot the pilot for Tales of the Tinkerdee, starring Kermit the Frog, Taminella Grinderfall and King Goshposh, characters who would all reappear a few years later in the Tales From Muppetland. In the book Jim Henson: The Works, Jerry Juhl spoke of Kermit's role in the show:

“Tinkerdee was a fairy tale kingdom and Kermit narrated the story in song. He had a lute, and you'd see him on little grassy knolls singing the narration we had written in the form of quatrains with god-awful puns and hideous rhymes, which he performed to very sweet, lilting music. That's how we made the transition from one scene to the next.”

(retrieved from archive.org)

Unfortunately, the pilot never aired, but you can watch it on Youtube.

A few years later, in 1965, Henson and Juhl created “Shrinkel and Stretchel,” a TV Commercial for Pak-Nit RX, loosely based on Hansel and Gretel by the Brothers Grimm.

You can also see Henson and Juhl’s Pal-Nit RX commercials “Shrinkenstein” and “Rumple Wrinkle Shrinkel Stretchelstiltzkin” on Youtube.

“Rumple Wrinkle Shrinkel Stretchelstikzkin”

Sounds like James Thurber to me!

Richard Hunt, Jim Henson, and Frank Oz on the set of Sesame Street

Sesame Street

In 1969, the Children's Television Workshop approached Jim to create and perform puppet skits and short animated films for their new television show aimed at preschoolers: Sesame Street. Jim was worried about being typecast as a children’s puppeteer—something that would bother him for most of his career—he wanted his puppetry to be edgy and avant-garde. Thankfully they convinced him, and the rest is history.

Throughout those early years, fairy tales, folklore, nursery rhymes, and many classic children’s stories found their way to 123 Sesame Street. One of my favorite recurring segments is “News Flash,” where Kermit the Frog is a reporter who interviews characters from fairy tales and other popular stories. They’re hilarious parodies where whatever could go wrong does. In the first “News Flash” skit (1972), Reporter Kermit covers the unfolding of the Rapunzel story. She’s stuck in a tower because of the wicked witch, but when the rude, lackluster Prince Charming asks her to let down her hair, she literally lets all her hair fall off her head!

News Flash Rapunzel skit, 1972.

Kermit’s frustrations with his idiotic interviewees and his deadpan humor are the secret sauce of these skits (watch this compilation video). Rapunzel is one of the best, but “Pinocchio” and “Mirror, Mirror” are also hysterical. Thankfully, the Muppet Fandom website— an invaluable resource— lists all the “News Flash” segments with links to watch them online.

Here’s another incredible Sesame Street fairy tale creation:

The Sesame Street Fairy Tale Album (1977) was nominated for a Grammy!

The Muppet Show cast, season one.

The Muppet Show

Never one to be pigeonholed, Henson continued to work on other creative projects during this time at Sesame Street. In 1970, ABC signed on to revive the television special Hey, Cinderella — a muppet fairy tale satire adapted from a failed Snow White pilot that Henson and Sesame Street’s director Jon Stone created in 1965. Henson was thrilled and turned it into a special series called Tales from Muppetland, which later included The Frog Prince (1969), The Muppet Musicians of Bremen (1972), and Emmet Otter's Jug-Band Christmas (1977) — a children’s book written by Russell Hoban and illustrated by Lillian Hoban. Jim had ideas for more Muppet Tales, like the adaptation of The 13 Clocks he’d always dreamed of, but none were produced.

"The one property I've wanted to do with the Muppets for twenty years.” Jim wrote of The 13 Clocks in his journals.

(via Jim Henson: The Biography by Brian Jay Jones.)

During this time, Henson began working on a new television show that would propel The Muppets to superstardom. In 1976, The Muppet Show aired on CBS. Kermit the Frog and his fellow Muppets put on a hilarious and provocative vaudeville variety show, along with famous special guest stars. The half-hour show was packed with musical and comedy performances that poked fun at Hollywood. It was a huge success, resulting in many feature films and television specials like The Muppet Movie (1979), The Great Muppet Caper (1981), and The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984).

Twiggy performing The King’s Breakfast on The Muppet Show

Like Sesame Street, The Muppet Show had plenty of absurd adaptations of children’s stories. In 1985, Playhouse Video released Children’s Songs and Stories (With the Muppets) —a compilation of songs and sketches from the show. Typically, a direct-to-video series is nothing to get excited about, but this is fantastic! There’s Robin the Frog singing “Halfway Down the Stairs” inspired by the poem “Halfway Down” (1924) by A.A. Milne, Twiggy performing The King’s Breakfast (1925) also by A.A. Milne, Brooke Shields as Alice in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll, “The Inch Worm” inspired by the film Hans Christian Andersen (1952), Kermit and Robin singing “The Octopus’s Garden” by The Beatles, and so much more.

Brooke Shields performing Alice in Wonderland on The Muppet Show

The Dark Crytal (1982)

The Dark Crystal and The Labyrinth

In the late ‘70s, Jim Henson was gifted a copy of Brian Froud’s fantasy art book The Land of Froud (1977). He was so impressed that he hired Froud as the conceptual designer for The Dark Crystal (1982), Henson’s first film without The Muppets. At the time, Henson had only a vague idea of the look and feel of the film. Some of his inspiration came from The Pig-Tale (1893), written by Lewis Carroll and illustrated by Leonard Lubin. The illustration of a wild crocodile lounging in a refined Victorian bathtub intrigued Jim. He loved the juxtaposition. But it wasn’t until he started working with Froud that the story began to take shape. The film is about Jen, a young Gelfling, who is on a quest to heal the dark crystal and save the planet from the rule of evil Skeksis. It’s a sensationally rich and breathtaking film that pioneered sophisticated radio-controlled puppetry. It’s no surprise that it was Jim Henson’s favorite project. There’s absolutely nothing like it.

The Pig-Tale (1893), written by Lewis Carroll and illustrated by Leonard Lubin.

Henson and Froud joined forces again on The Labyrinth (1986), a rock opera film that follows the young teenager, Sarah (Jennifer Connelly), who’s upset that she has to babysit her baby brother Toby. She wishes the goblins would come and take him away. But her wish is granted, and the Goblin King (David Bowie) gives her 13 hours to solve the labyrinth before Toby is turned into a goblin forever.

The Labyrinth (1986)

Without question, The Dark Crystal is Henson’s cinematic masterpiece, but The Labyrinth resonates more with me. As a young girl, I leaned on my imagination to overcome difficult times. I’d filter out the real world by secluding myself in my bedroom, where I could freely act out my fantasies. I recognized Sarah’s need for a made-up parallel world. The Labyrinth acknowledges that childhood can be scary and dangerous. It’s filled with potential threats, wrong turns, dead ends, and troubling thoughts. You feel like, at any moment, the ground may fall out from underneath you.

It’s as if Henson, like the Brothers Grimm, collected all the poems and stories he’d loved and remixed them into his own dark and meaningful fairy tale. And there are references to many of his influences in the film. Sarah owns several fantasy books, including, The Wizard of Oz (1900) by L. Frank Baum, Walt Disney's Snow White Annual (1938), Alice in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll, Grimms’ Fairy Tales (1812), Hans Christian Andersen Fairy Tales (1835), and Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (1963) and Outside Over There (1981). In fact, the movie’s premise was so close to Sendak’s Outside Over There it was almost shut down by a lawsuit, and Henson ended up acknowledging Sendak in the film’s credits. But Henson and Sendak were fans of one another. Sendak was an early member of the National Board of Advisors for the Children's Television Workshop during the development stages of Sesame Street. And in the early ‘70s, he collaborated with Henson on two animated shorts for the show, “Seven Monsters” and “Bumble-Ardy,” however, both were eventually pulled because they were considered too scary for children.

Maurice Sendak eventually reworked both of his Sesame Street animations into children’s books.

John Hurt and Jim Henson on the set of The Storyteller (1987-1989)

The Storyteller

One of Jim Henson’s most brilliant achievements was The Storyteller (1987), an enchanting series of folktales and Greek myths reinterpreted for television. Along with screenwriter Anthony Minghella, Henson combined the richness of ancient tales with modern technological artistry. The stories were narrated by the talented John Hurt and his companion, a hilarious talking dog, performed by Henson’s son Brian. The pilot episode, “Hans My Hedgehog,” is based on the Grimms’ fairy tale and was conceptually designed by Brian Froud (The Dark Crytal and The Labyrinth). Everything is meticulously crafted, from the creatures, to the clothing, to the music— it all sets the stage for the rest of the remarkable series.

Despite its success with audiences and critics, the show was canceled after only nine episodes. But in 1990, it was revived with a spin-off, The StoryTeller: Greek Myths, and reimagined in a series of graphic novels and comic books. In 2019, The Henson Company and Neil Gaiman announced they were in the development of The Seven Ravens, a new chapter of The Storyteller.

Jim & Jim

“When people told themselves their past with stories, explained their present with stories, foretold the future with stories, the best place by the fire was kept for the storyteller.” — The Storyteller

Jim Henson is The Storyteller. He may no longer be with us, but his fantastic stories live Happily Ever After.

Once upon a time, most likely 1999. Cinderella with her wicked stepmother and two evil stepsisters.

Love this, Taylor. The Koozebane sketch is a favorite in our family...as well as Mah Na Mah Na.

He was a genius.

This was excellent, Taylor. I’m a huge Henson fan and it was a pleasure to see you dive into his work this way. (I just watched Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas the night before last — not with my children, either 😂)

I’m so glad I found your newsletter this year — I always know, when I see it in my inbox, that’s it’s going to be interesting and insightful, so thanks for that, and keep up the amazing work!