Moonbow is a reader-supported publication. It exists because of the support of generous readers like you! If you enjoy Moonbow, the best ways you can support it is to subscribe, share this newsletter with a friend, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

I’ve always been fascinated with fairy tales and folktales, but more recently—probably from reading Hilary Mantel’s ‘Wolf Hall’ trilogy—I’ve become obsessed with everything medieval. I love exploring the historical connections of fantastical tales and thinking about what those connections reveal about us as human beings. I’m also interested in the ways medieval history, psychology, and fairy tales weave themselves into children’s literature and how that’s evolved over time.

Here are some of the things I’ve been exploring and enjoying:

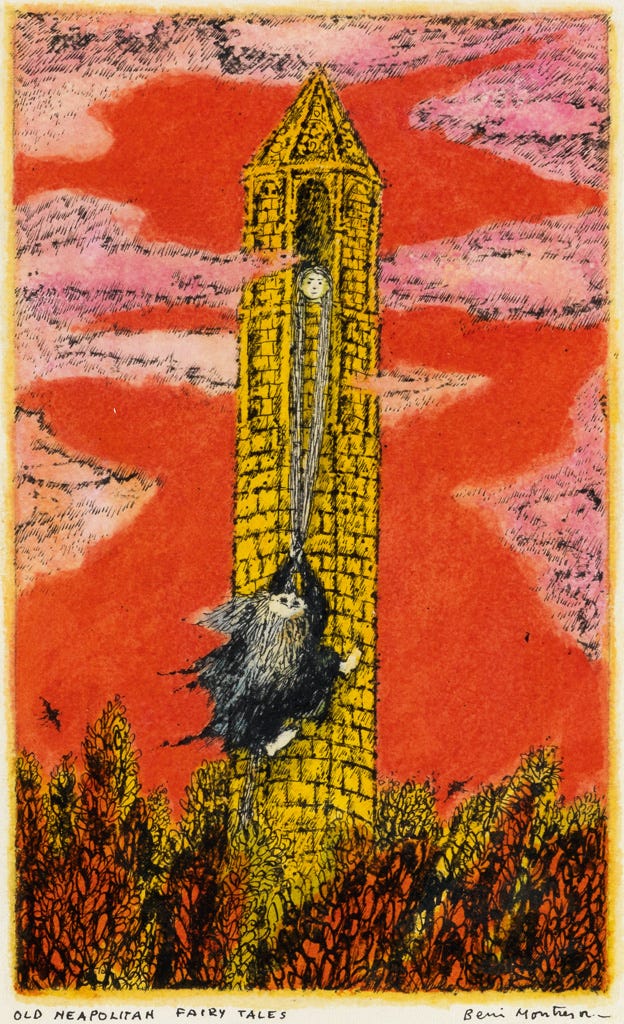

Beni Montresor’s Fairy Tales

Beni Montresor is one of my favorite children’s book authors and illustrators, but he was also a great opera director and set designer. I first became interested in Montresor after seeing his captivating line drawings in Belling the Tiger (1964), written by Mary Stolz. But it wasn’t until seeing his Caldecott medal-winning illustrations in May I Bring a Friend? (1964), written by Beatrice Schenk de Regniers, that I became a super fan. It’s the story of an audacious young boy who, when invited to visit the King and Queen, asks if he can bring a friend. And not just any friend—a giraffe! The extremely generous and patient King and Queen welcome them both happily—and continue to invite the boy back every day that week. Each time he asks if he can bring a friend: hippos, monkeys, elephants, lions—they’re all welcome! The combination of Schenk de Regniers’s charming musical verse and Montresor’s sumptuous illustrations makes each page turn a thrilling experience.

Montresor illustrated many fairy tales, like The Princess (1962), Little Red Riding Hood (1991), Cinderella (1965), The Nightingale (1985), Hansel and Gretel (2001), and the collection Old Neapolitan Fairy Tales (1963). But what’s been on my mind recently is The Witches of Venice (1963). Unlike the friendly King and Queen in May I Bring a Friend?, the King and Queen of Venice are dismissive and cruel. They desperately desire a child, but when the fairies offer them a magical plant that will turn into a boy, the king refuses to believe them and chucks the plant out the window. When the plant does bloom into a boy, the king continues to reject him and makes him a prisoner in the castle courtyard. But soon, the poor flower-plant boy discovers the existence of a little flower-plant girl who is being held captive by the Witches of the Grand Canal, and he escapes to rescue her. It’s a story of adventure and friendship filled with fairies, monsters, and witches!

In the mid-nineties, the innovative composer and pianist Philip Glass was commissioned by the Teatro alla Scala to work with Montresor to adapt the book into an opera-ballet for children. I wish I could have seen this, but I was able to listen to the soundtrack on Spotify. Glass brings this fantastical tale to life through his inventive and energetic music. And it creatively combines my two loves: experimental music and children’s literature.

The Sun King & The Moon Queen

Recently, I took my children to Children’s Fairyland in Oakland, California. Despite it being a Bay Area staple since 1950, I had never been. It’s like stepping foot into a fairy tale storybook—it’s amazing! I wanted to make sure my kids got the chance to experience it before they protested that they’re “too old” for such things (they’re 6 and 9), but really I went for a selfish reason: I wanted to see the Storybook Puppet Theather that the famous Muppet puppeteer Frank Oz worked at as a young man. The kids grumbled a little but then came home and proceeded to put on their own puppet show. So I consider it a win-win!

One of my favorite attractions was the Children’s Chapel of Peace, a tranquil resting place within this fantastical world. Inside, there’s a beautiful stained-glass window of the sun and the moon. It stood out to me. Probably because of my obsession with the moon, but also because of the things I’ve been reading, like The Moon Queen from the graphic novel The First Cat in Space Ate Pizza, The Sun King (which I’ve not read but am intrigued by), and the famous psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s alchemy studies in The Psychology of the Transference. In the book, Jung employs a series of ten illustrations from Rosarium Philosophorum (Rosary of the Philosophers), where, according to Stephan A. Hoeller from the website “The Gnosis Archive,” the dual powers of the “King”(sun) and the “Queen”(moon) join forces and undergo a series of phases.

“…the ‘King’ and ‘Queen’ are shown to undergo a number of phases of their own mystico-erotic relationship and eventually unite in a new, androgynous being, called in the text ‘the noble Empress’. The term ‘transference’ is used by Jung as a psychological synonym for love, which in interpersonal relations as well as in depth-psychological analysis serves the role of the great healer of the sorrows and injuries of living.”

This is a bit complicated to fully explain here (I recommend Googling Rosarium Philosophorum sequence), but ultimately, what I find fascinating, is the belief that a proper balance between feminine and masculine relationships must be established in order to achieve full experience of the Spirit. The two forces must merge together in their naked truths and reconcile their emotive, intellectual, physical, and metaphysical opposites in order to transform into a newly formed consciousness—a psychological mechanism of love.

Katherine Rundell: The Golden Mole

A few years ago, I picked up a pocket-sized book with the intriguing title, Why You Should Read Children’s Books Even Though You’re So Old and Wise (2019) by the children’s book author Katherine Rundell. At the time, I was a budding children’s book evangelist, but it wasn’t until reading Rundell’s brilliant essay that I felt completely justified in my mission. This tiny book covers a lot of ground, blazing through the history of children’s literature, the importance of fairy tales, the urgency for greater diversity in authorship and representation, and the critical need for library funding. It easily could have been a dull book, but Rundell writes about big topics swiftly and persuasively, employing her dazzling wit and vivacious energy in every sentence.

Rundell on fairy tales:

“Fairytales, myths, legends: these are the foundation of so much, and as adults we need to keep reading them and writing them, repossessing them as they possess us.”

On why adults should read children’s books:

“Children’s books are not a hiding place, they are a seeking place. Plunge yourself soul-forward into a children’s book: see if you do not find in them an unexpected alchemy; if they will not un-dig in you something half hidden and half forgotten. Read a children’s book to remember what it was like to long for impossible and perhaps-not-impossible things. Go to children’s fiction to see the world with double eyes: your own, and those of your childhood self. Refuse unflinchingly to be embarrassed: and in exchange you get the second star to the right, and straight on till morning.”

Amen.

Her most recent book, The Golden Mole and Other Living Treasures (2022), is another example of her infectious enthusiasm. In this fascinating 21st-century bestiary of the world's most extraordinary endangered animals, Rundell makes a case for wonder. Through this collection of essays beautifully illustrated by Tayla Baldwin, Rundell invites us to pay attention to miraculous creatures but also to pay attention to our attention.

If you’ve followed me for some time, you know that attention, delight, wonder—these are my guiding principles. My company Glitter Guide’s tagline was “Flashes of Delight,” a play on the definition of glitter: “flashes of light.” Our mission was to encourage readers to stop and look around, to pay attention to tiny moments of delight, the ones you could easily miss if you weren’t actively acknowledging the brilliance of our painfully exquisite existence. It sounds a bit lofty, but it’s true: to practice awe, as Rundell often says, requires a “ferocious discipline”.

“Attention is the thing we offer, that we owe most to the world we live in.”

In The Golden Mole, this attention is paid to marvelous animals: wombats, hares, swifts, lemurs, wolves, pangolins—all of which are at risk of extinction. Her essays are breathtaking acts of storytelling. One of my favorites is “The Seahorse.” Ever since I was a young girl, I’ve been astounded by these tiny, mythical-looking creatures. They feel like proof that fantastical worlds truly exist.

“We live in a world of such marvels. We should wake in the morning and as we put on our trousers we should remember the seahorse and we should scream with awe and never stop screaming until we fall asleep, and the same the next day, and the next. Each single seahorse contains enough wonder to knock the whole of humanity off its feet, if we would but pay attention.”

Many of the essays in The Golden Mole read like fairy tales. Like her story about wolves and how they have often been used as symbols of our hidden appetites.

“A true fairytale wedding would be one in which secret desires leak out: one in which the ageing prince, tired of waiting for his throne, turns into a wolf and eats the queen.”

And similar to fairy stories, these essays pack the most punch when read out loud. I’ve been reading one essay a night to my children, and each time we’re left feeling wrecked, intoxicated, and ready to take action!

Angela Carter’s Radio Plays

“The eye sees more than the heart knows.” —William Blake

How do I love Angela Carter? Let me count the ways! I wish I could go into depth about Carter, but that’s a tale for another newsletter. She’s the invisible thread that runs through my interests in fictional stories—not only the ones in books—but also the ones we tell ourselves. Reading her stunning, gut-wrenching Bluebeard-esque fairy tale, The Bloody Chamber, was a mind-blowing experience.

Like Katherine Rundell, Carter is a ‘maximalist’ writer with rich, imaginative language and exuberant vivacity. She wasn’t afraid of grandiosity, in fact, she preferred it. Reading Carter’s fiction is an intense, tantalizing, erotic, sensual experience—it speaks directly to our carnal desires. They are stories are about hunger: hunger for love, for power, for transformation—they are everything primitive and fundamental, they are stories that live forever.

In Rundell’s Why You Should Read Children’s Books, she talks about the elasticity of fairy tales. They are stories designed for change. To keep them the same would be strange. Angela carter knew this. She wasn’t satisfied with simply retelling these traditional stories; instead, she extracted their core ingredients and wrote a completely new recipe.

“I am all for putting new wine in old bottles, especially if the new wine makes the old bottles explode.” —Angela Carter

The stories in, The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories (1979), are astonishingly vivid, they stimulate the senses, and reverberate throughout the body. Her imaginative storytelling and evocative narrative voice are, according to Carter, best suited for the radio. She believed in the perplexing paradox that radio was the most visual of mediums, that it was not a limitation, but rather, a multiplication of narrative possibilities. In the introduction to her collection of four radio plays, Come Unto These Yellow Sands (1985), she writes:

“It is the necessary open-endedness of the medium, the way the listener is invited into the narrative to contribute to it his or her own way of ‘seeing’ the voices and the sounds, the invisible beings and events, that gives radio story-telling its real third dimension…”

Carter enjoyed the flexibility and freedom of writing for the radio. She could blur the linearity of narrative fiction and layer a kaleidoscope of narratives all happening at the same time. It requires the listener to enter a liminal space; they have to fill in the gaps with their imagination, they have to see the sounds. Carter refers to them as “aural hallucinations”. Her radio plays, broadcast in the ‘70s and ‘80s, take full advantage of the expansiveness of the format. Vampirella (1976) was Carter’s first piece written for the radio. After this, she would write Come Unto These Yellow Sands (1979), The Company of Wolves (1980), Puss-in-Boots (1982), and A Self-Made Man (1984). As much as I adore Carter’s stories and novels, I think her radio plays may be my favorite. They bring together all the things that Carter was trying to do in her other writings, but in a uniquely entertaining way. They’re manifestations of Carter’s keen understanding of the sensual, sonic power of storytelling.

“In its most essential sense, even if stripped of all the devices of radio illusion, radio retains the atavistic lure, the atavistic power, of voices in the dark, and the writer who gives the words to those voices retains some of the authority of the most antique tellers of tales.”

—Angela Carter, Come Unto These Yellow Sands (1985)

You can listen to the original broadcasts of Vampirella and The Company of Wolves here. And check out Writing in Three Dimensions: Angela Carter’s Love Affair With Radio, and The Angela Carter BBC Radio Drama Collection.

There's so much depth and richness here, Taylor -- wow.

I loved May I Bring a Friend? as a child. It's one of those books that, upon seeing it as an adult, caused in me a strange, visceral reaction -- total recognition that once upon a time, I fell face-first into it and lived in it for the time it took to read it. So thank you for introducing me to The Witches of Venice -- it sounds like my kind of book through and through. (And I am ALWAYS here for a children's opera, especially once written by Philip Glass!)

This line from Rundell really nails it for me: "“Children’s books are not a hiding place, they are a seeking place." YES. 1000 times yes. (You share this so beautifully in this newsletter. I'm truly jealous.)

Also this: "We should wake in the morning and as we put on our trousers we should remember the seahorse and we should scream with awe and never stop screaming until we fall asleep, and th same the next day, and the next." I'm in full agreement.

Those quotes from Rundell are SO good and exactly why I love a good fantasy read. And I love the line about children’s books being a seeking place - how very true.