“Can you tell me a story?” My 7-year-old son asked while slurping a big spoonful of marshmallows from his bowl of cereal. It was early; the sky was still dark as night. My husband and daughter were cozy asleep in their beds, and my coffee had yet to kick in. I was not in prime storytelling shape. “How about we tell one together?” I suggested, knowing he’d eagerly take over, allowing me more sleepy-zombie-mommy-coffee-time. “What should the story be about?” he asked. I looked at a note I had scribbled on a nearby notepad. “How about a skeleton’s garden?” I asked. And that was it; he jumped right in without hesitation. He knew that this was a fairy tale about an old farmer who loved to plant cabbages. His cabbages were the best in the land. Then, one night, someone—a witch—had snuck into his garden and put a spell on his special cabbages, a poisonous spell. So when the farmer woke the next day and took a bite of his beloved cabbage, he immediately keeled over and died, leaving the cabbages all to the wicked witch. But a year later, buried deep down in the garden soil, among worms and bugs and eerie things, laid the skeleton of the restless, vengeful farmer who was determined to catch the witch and take back his garden.

Hearing this story, I no longer felt drowsy; I was rapt. This kid knows how to tell a story, I thought. But because he’s 7 and not me—an adult obsessed with a good story—he got distracted by the lack of marshmallows left in his bowl and moved on. I, on the other hand, have been obsessively wondering how the story ends. Of course, I could come up with my own fairy tale ending, but I’d rather know his. Did the skeleton catch the witch? Surely. But if my son were telling it, this story would have delightfully gone off the rails somehow, like the introduction of an alien spaceship crashing into the farmer’s garden. Then, the aliens abduct the witch and ship her to Mars, where she’s held prisoner and forced to eat dry cereal without any marshmallows for eternity. The End.

The story wasn’t the only thing that got me thinking; it was how my son immediately and confidently knew what it was about. I was envious of how he could dive in and out of his imagination without skipping a beat. I thought of a quote I’d read by the famous children’s book author-illustrator Maurice Sendak:

“Children do live in fantasy and reality; they move back and forth very easily in a way we no longer remember how to do.” 1

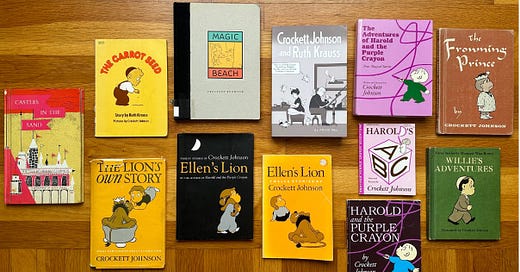

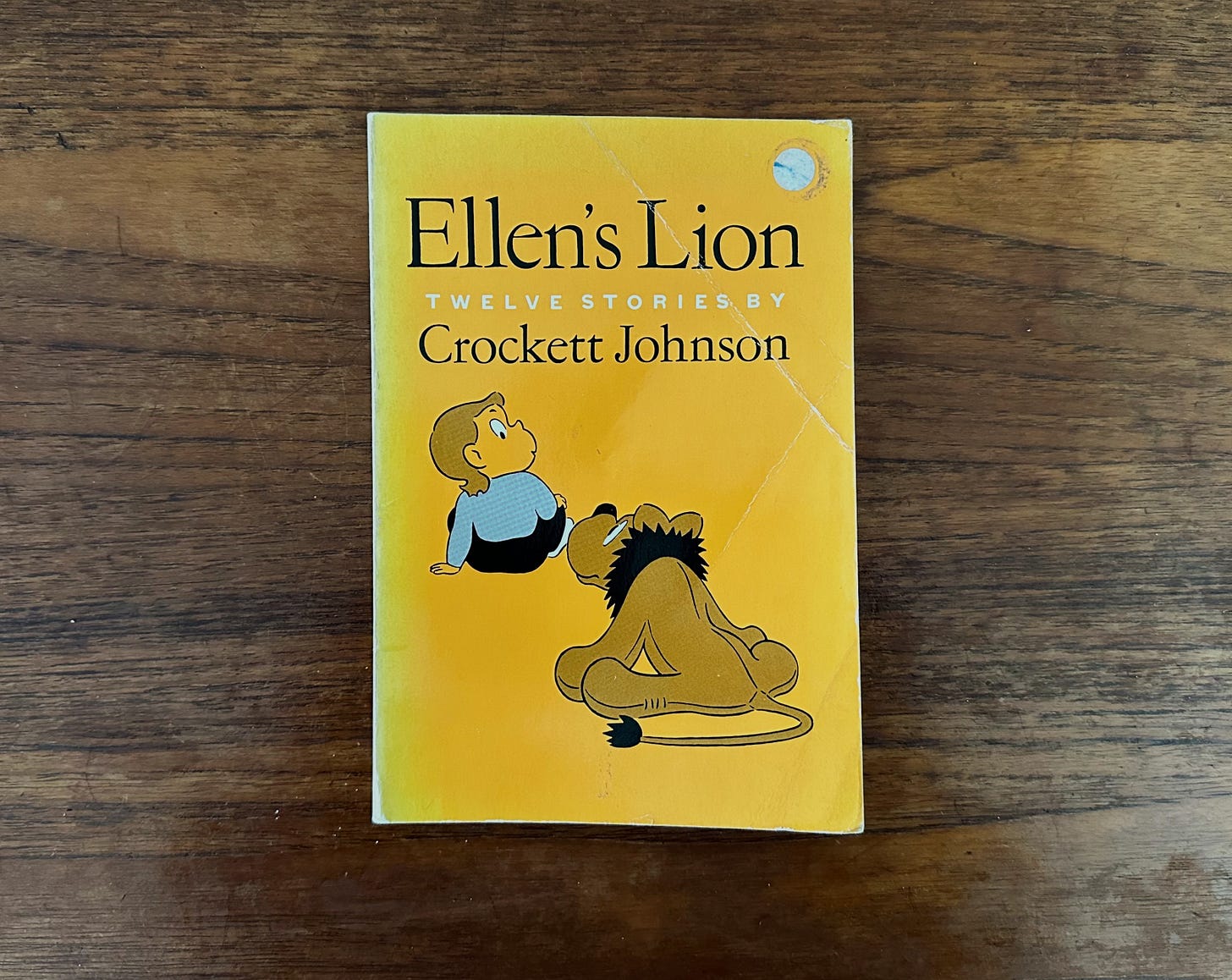

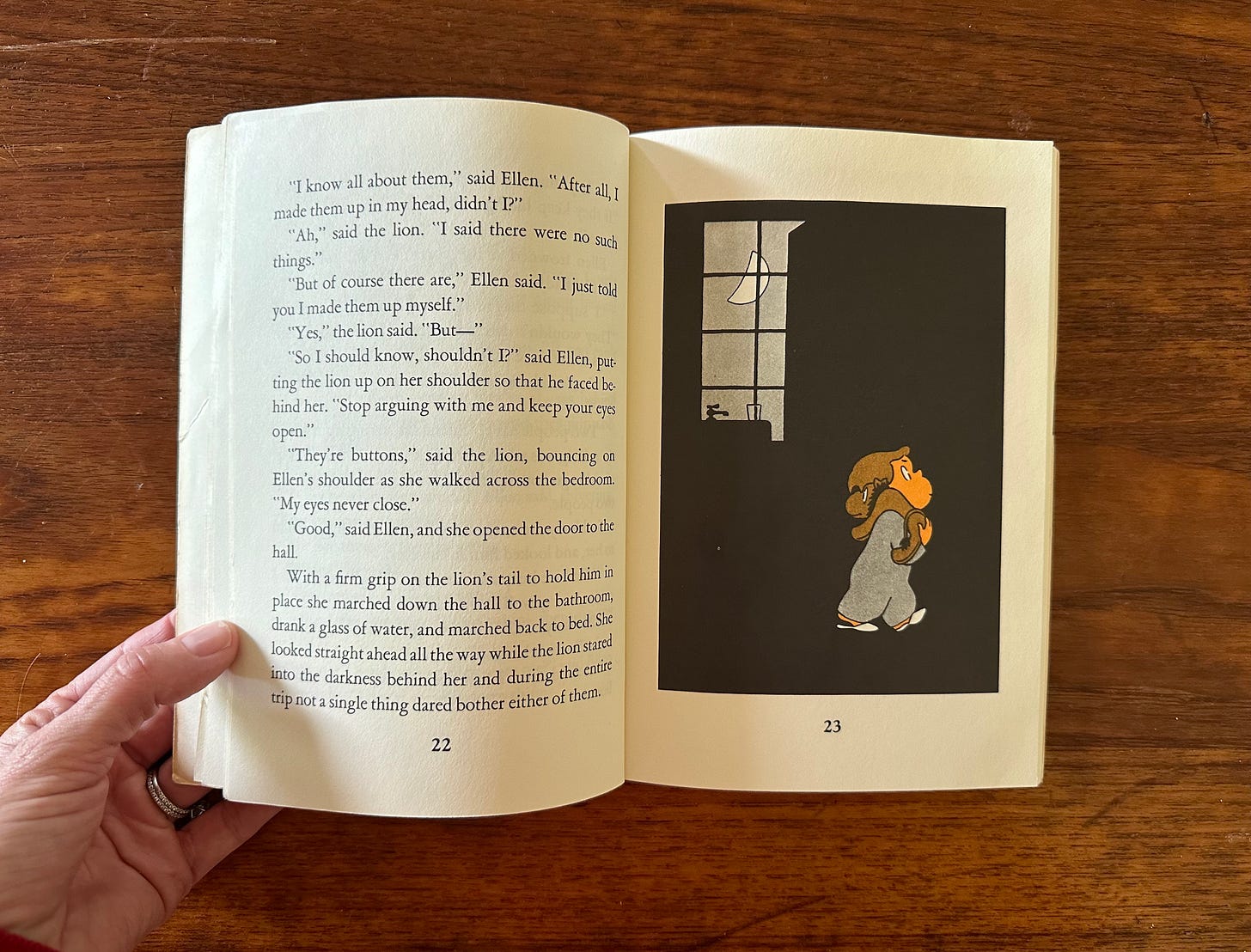

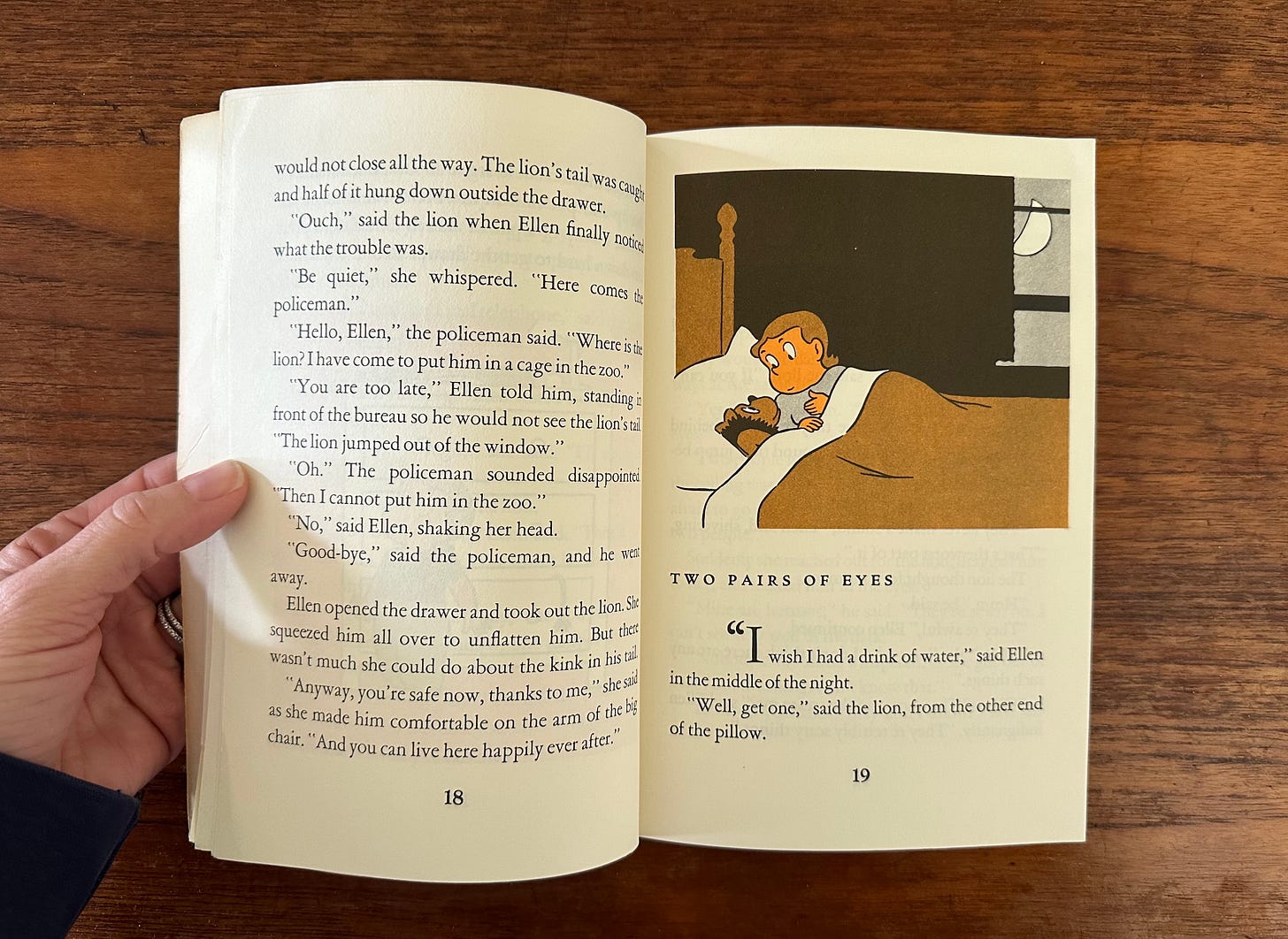

It also reminded me of one of my favorite children’s books, Ellen’s Lion, by Sendak’s mentor and close friend, Crockett Johnson. It’s a series of 12 short stories about Ellen, a spirited young girl who uses her robust imagination to engage in skits, stories, songs, and, sometimes, Socratic dialogue with her best friend, a stuffed lion. Like my son, Ellen effortlessly transitions between fantasy and reality. Her imagination has gaps where reality slips in and out; there are conflicts in the details. Imaginative play is full of inconsistencies. The fantastical and mundane swirl together, like in a dream. Reading stories that feel like dreams can be stressful, but not with Johnson; he keeps the stories tight: they’re funny and warm and almost always end on a perfectly abrupt note.

Ellen’s Lion, published in 1959, is like Johnson’s other books for children: perceptive and precise, with dry, laconic humor, full of imaginative possibilities, but at the same time, its format is unlike his other books, or really any other children’s book. It’s not a picture book, chapter book, early reader, graphic novel, or even a collection of short stories—at least not in the way we think of them for adults. It’s more like a play or a newspaper comic strip; the conversations are broken into philosophical and comedic moments but without the tight constraints of tiny panels and speech bubbles. Still, the stories are short, only a few pages long, each with one or two illustrations. There’s no traditional plot, and each story can hold its own, but the pleasure of reading this book comes from getting to know these characters and anticipating how they might respond in various situations. And you can only do that if you read all of the stories.

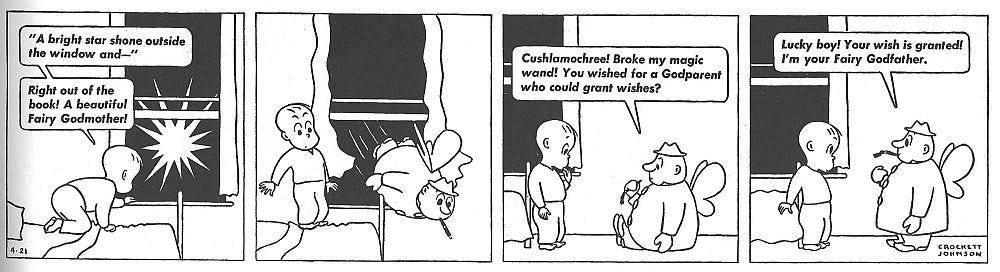

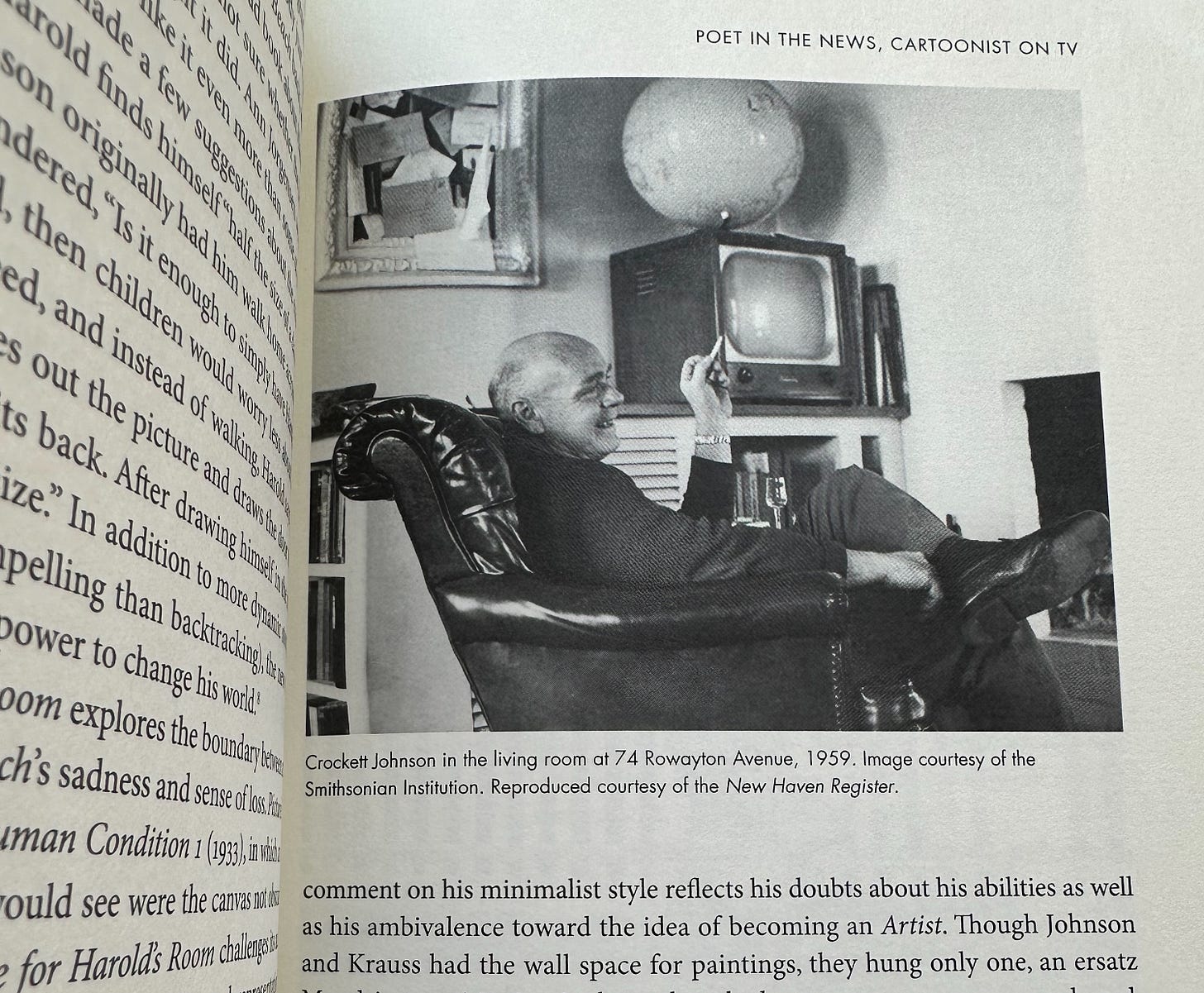

It’s a little like reading a collected anthology of the Calvin and Hobbes comic strips. Actually, the premise is a lot like Calvin and Hobbes (1985-1995). Both are about a precocious young child who creatively imagines their favorite stuffed animal into being, and both are humorous and insightful with sophisticated language and a complex narrative conceit. Now that I think about it, it’s unsurprising that Ellen’s Lion feels like a comic strip, even though it doesn’t resemble one. Before children’s books, Johnson was a successful cartoonist. In the 1930s, he drew comics for the political publication New Masses and, later, Collier’s. His first commercial success came in 1942 with his daily comic strip Barnaby. While not an immediate smash hit, it developed a cult following over its 10-year run, with a devoted fan club that included Dorothy Parker, Duke Ellington, and Charles Schulz. Parker wrote that Barnaby was "the most important addition to American arts and letters in Lord knows how many years." And the American painter Rockwell Kent wrote, “I yield to no one in my ‘blathering admiration’ of Barnaby.” Chris Ware, one of the most uniquely talented comic artists working today, wrote in his introduction to Barnaby, Volume One (2013), “I never thought I'd see this day, but the book you hold is, well… the last great comic strip. Yes, there are dozens of other strips worth rereading, but none are this Great; this is great like Beethoven, or Steinbeck, or Picasso. This is so great it lives in its own timeless bubble of oddness and truth…"

Barnaby was truly one-of-a-kind, with clever, sophisticated humor that not only spoke to the well-educated but to a mass audience, including children. It’s also the only strip to regularly feature typeset dialogue. Instead of hand-lettering, Johnson used Futura Medium Italic, a modern font choice, especially for the early ‘40s. He also drew the speech bubbles first and then pasted the written portion into them, which takes incredible planning and precision. This typographic style would become Johnson’s trademark.

The strip features Barnaby Baxter, a bright young boy who, one night, after reading a fairy tale with his mother, is visited by his fairy godfather, Mr. O’Malley, through his bedroom window. But unlike the fanciful fairy godmothers we’re familiar with, Mr. O’Malley is a short, portly man in a trench coat and hat with pink wings and a cigar for a magic wand. He’s fabulously fallible—a real buffoon—with bumbling magical abilities and a penchant for gambling, and yet, despite his quirks, or perhaps because of them, Mr. O’Malley is remarkably loveable, especially to Barnaby, who never loses faith in his flawed fairy godfather. But Barnaby’s parents never believe in Mr. O’Malley, no matter how hard Barnaby tries to convince them. The humorous tension between the two conflicting realities (Barnaby’s and his parents’) is at the heart of the strip. Barnaby’s fantastical world is absurd to the adults, but to him, it’s the adult world that’s bewildering. Even we, as readers, become convinced that Mr. O’Malley could be real (he’s elected to Congress!), but his realness is not entirely unequivocal. Barnaby’s imagination is rooted in the reality of everyday life, and the balance between the two is fragile.

In Barnaby, Volume One—the first published collection of the original strips—the author and cultural critic Jeet Heer wrote:

“In the world of Barnaby there is a constant tension between the narrow-minded philosophy that only believes what it sees and the equally dangerous tendency of letting belief guide sight. The first philosophy leads to a soul-crushing empiricism that denies the imagination any freedom, while the second philosophy leads to flights of unreality (of the type that Mr. O’Malley specializes in). Barnaby has to walk a tightrope between these two philosophies, making sure that he balances his imagination with his sense of reality.”

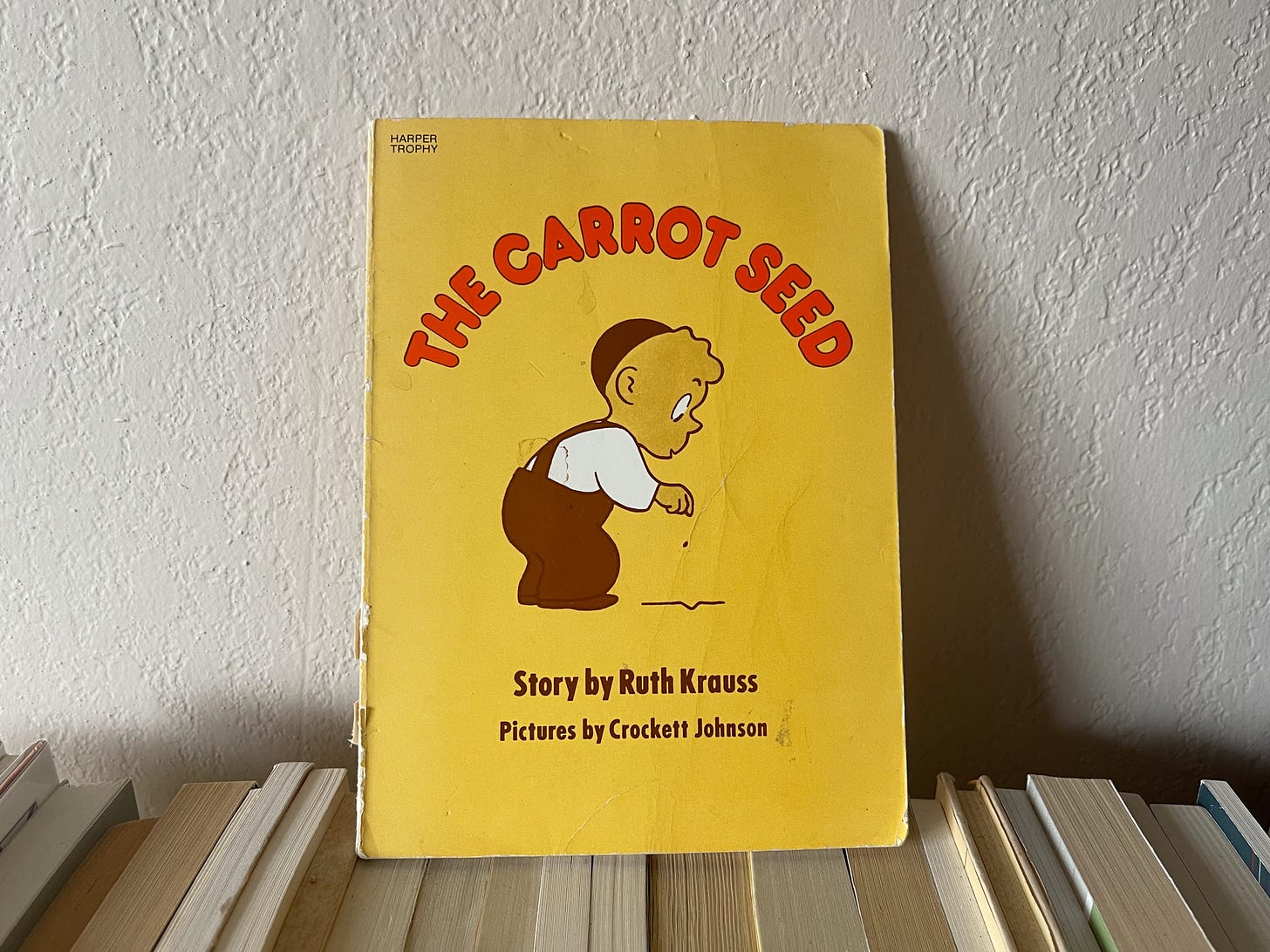

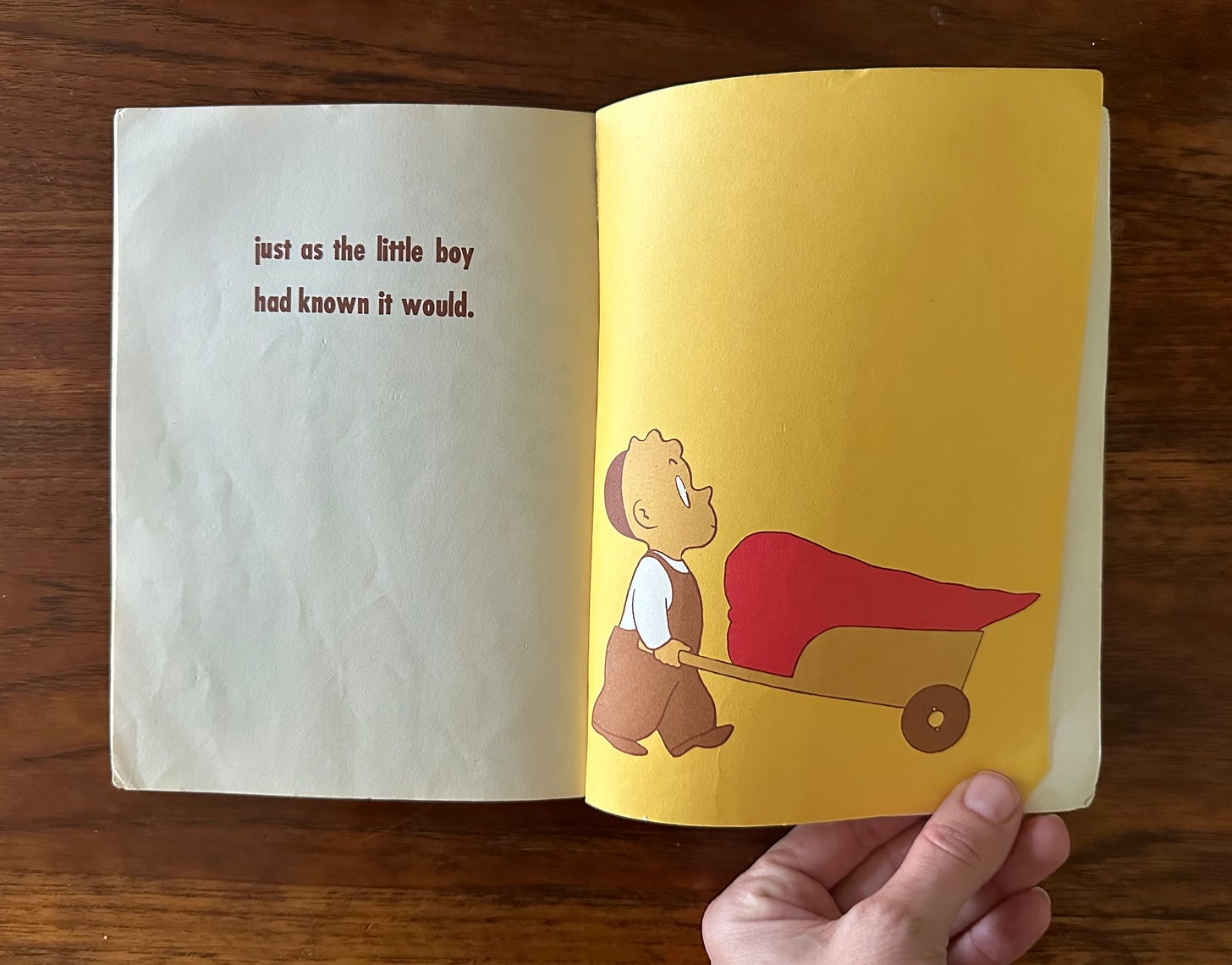

While working on Barnaby, Johnson began illustrating children’s books. His first, The Carrot Seed (1945), was written by his wife, fellow acclaimed children’s author Ruth Krauss, who famously collaborated with Sendak on A Hole is to Dig (1952) and many other revolutionary children’s books of the ‘50s. Krauss and Johnson didn’t have children of their own, but they shared a keen understanding of what it means to be a child, and they were fascinated with the child’s imagination. This time, it’s not the belief in an absurd fairy godfather but in a carrot seed. A little boy believes his seed will grow into a carrot despite the doubts of his naysaying parents and older brother. But his belief is steadfast, and with time and attention, his seed turns into a colossal-sized carrot.

The book is sparse but warm. Text and image, composition and color, are distilled to their cleanest, simplest forms—resulting in a deceptively simple and delightfully subversive little book. From page to page, it speeds along; everything is plain in brown and yellow and white, but then, suddenly, a pop of green grabs your attention; you turn the page one last time, and WOW!—an astonishingly big orange carrot is revealed. (This carrot is so big it’s bigger than the boy!). The whole experience is deliciously satisfying, especially for children, who relish the fact that this kid just outsmarted both his parents and older brother. Adults like it too, although usually for different reasons. It’s a book that satisfies different cravings, which is why, for almost 80 years now, it’s never been out of print.

Sendak admired it, too. In his essay, Ruth Krauss and Me, Sendak wrote:

“…that perfect picture book, the granddaddy of all picture books in America, a small revolution of a book that permanently transformed the face of children’s book publishing. The Carrot Seed, with not a word or a picture out of place, is dramatic, vivid, precise, concise in every detail. It springs fresh from the real world of children.” 2

It’s a true feat in bookmaking. Like the seed, this book is small and unassuming, but the more you pay attention to it, the bigger it gets.

Johnson’s concern with children’s imagination is a constant theme throughout his work, but it’s never explicitly said. It’s more like a whisper. It lingers in your ear. You only hear parts of it. Maybe a word or two. And right when you think you understand it, poof—it disappears. You shake your head, trying to get another listen, but where there were once words, now there is only feeling. To repeat it would be fiction. It’s something new now, and it belongs to you.

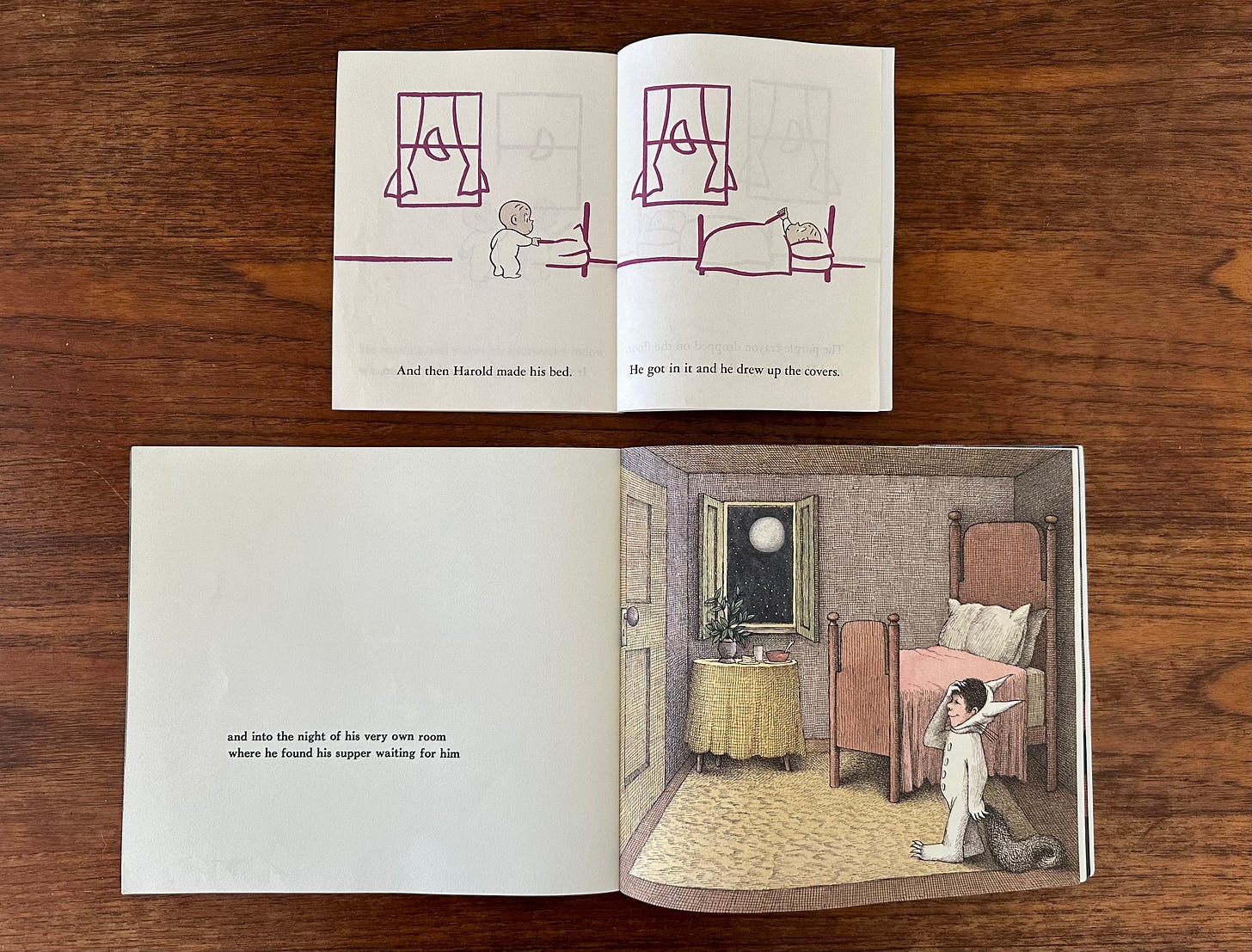

The most striking example of this is Johnson’s picture book masterpiece Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955). Chances are, if you’ve heard of Johnson before, it’s because of Harold.

The book, like Harold’s world, is a blank canvas, except for the one Harold decides to create. Armed with nothing but a purple crayon and his imagination, Harold draws himself out of the void and into his fantasies. He is free to create anything he desires, and what he creates is vivid and appealing. There are enchanted forests, sailboats, tall mountains, expansive cityscapes, and the constant comforting presence of the crescent moon, all drawn in a deep, rich purple. According to Johnson, “Purple is the color of adventure.”3

Harold’s creative adventure is liberating, but his triumphs are short-lived. Each time he draws an opportunity, a new challenge occurs; he has to improvise under pressure. If you think about it, Harold has to use his purple crayon to stave off hunger, fight off a dragon, escape from drowning, and avoid plummeting to his death. It’s no wonder he gets tired and wants to go home. But he can’t; he’s lost in a world of his own making.

In the end, Harold is only able to find his bedroom by drawing it. He remembers where his window is in relation to the moon in the sky and uses his purple crayon to draw himself under it, tucking himself into the covers of his cozy bed. But this is not the tidy ending that some readers want it to be; rather, it feels more like life: vague and confusing. Did he actually make it home? Where are his parents? Does he have parents? The ambiguity is unsettling, but also the point. Without an explanation, we’re forced to imagine one for ourselves. The mystery draws us into the story; we fill in the white space with our imaginations just as Harold draws in his with a purple crayon.

The story is an uncertain, porous thing. It feels unfinished and, in a way, authorless, like an old shapeshifting folktale you can’t quite grab hold of. It’s a story for everyone and no one, which is why it’s susceptible to so many different interpretations. Some think it’s empowering and encourages children to follow their dreams no matter the obstacles. Others think it’s an existential nightmare.

In his introduction to Barnaby, Volume One, Ware wrote:

“Crockett Johnson’s work scared the heck out of me. Long before I found Barnaby, I read Harold and the Purple Crayon. For those who aren’t familiar with Harold, the book turns on the single simple idea of a small, flatly-drawn boy in footie pajamas who both explores and makes his world solely by the marks of a thick purple crayon. From page to page Harold stays exactly the same size while his drawings—mountains, seas, flowers, pie—enlarge, dwarf and very nearly swallow him. Shallowly-read, it seems a perfect librarian-pleasing homily to the value of imagination and creativity, but the very impulses which amuse Harold also finish him: at the book, weary of his exploring, he goes home and goes to sleep. Or, more precisely, he outlines his own bedroom and bed, and ‘draws himself’ up and into the covers. The metaphysical implications of this hugely isolating ending still upset me. But presented in Johnson’s characteristically gentle whimsy, the page-turning impetus that gets you there feels just timed enough with the momentum of thought that it all goes down more or less painlessly.”

When I read Harold and the Purple Crayon, I land somewhere in the middle of hope and despair, which is how I feel whenever I do anything difficult and worthwhile. I’m emboldened by my imaginative powers, and at the same time, I’m terrified that, in the end, they’ll eat me alive.

It reminds me of Max in Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (1963), a book obviously inspired by Harold but reimagined in classic Sendakian fashion.

When Max’s mother sends him to his room for being too wild, he escapes into a moonlight fantasy, sailing to a kingdom of wild things. They’re monsters with frightening, terrible roars and terrible teeth, but Max isn’t afraid. Unlike at home, where his parents make the rules, in the land of the wild things, Max is king. Here, his wildness is not only appreciated, it’s loved. But all that wild rumpus-ing becomes too much of a good thing, and Max decides he wants to go home where he is loved best of all. Max’s desire for freedom but need for security is a paradoxical feeling we all relate to, but it’s especially true for children.

Sendak and Johnson were very aware of what it felt like to be a kid in the world and how different that is from being an adult. Although neither were particularly bothered with writing for children. They just wrote the truth of their lived experiences. In a 2005 interview with NPR, Sendak credited Johnson and Krauss for helping him recognize that.

In the same interview, he spoke about the enduring appeal of Harold and the Purple Crayon.

“Harold is just immense fun; that's all, just fun…Harold does exactly as he pleases. There are no adults to demonstrate or remonstrate. It comes out of the same theory: Let the kid do his own thing. Let him have fun. It's fun. Not to teach; there are no lessons in ‘Harold.’ You have fun, you do what you like and no one's going to punish you. You're just a kid.”

Sendak’s probably right. After reading Harold, I doubt children are having an existential crisis—that’s the adults. Maybe it is just fun. But the word “just” seems like an oversimplification. I think children recognize Harold’s struggle; they know that even in extraordinary moments there are challenging restrictions. Most of the time, the creative process is not just fun; it’s also frustrating and takes great effort.

Children are much better at make-believe than adults. Ellen knows her talking lion isn’t real, but she also doesn’t know. She has the power to make herself believe. We assume Calvin does, too—we just don’t see it. In The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book (1995), Watterson explains “Calvin sees Hobbes one way, and everyone else sees Hobbes another way. I show two versions of reality, and each makes complete sense to the participant who sees it. I think that’s how life works. None of us sees the world exactly the same way, and I just draw that literally in the strip.”

But Ellen sees her lion both ways, and we get to witness her process. We’re made aware of the artifice.

We go through a similar process when we read fiction. As fiction readers, we engage in a sort of satirical doublethink4 where we simultaneously hold two individually exclusive ideas. While reading, we inhabit the slippery in-between space of the two opposing binaries in order to suspend disbelief. When we read Ellen’s Lion, we stand unsteadily between fantasy and reality, but these worlds collide so rapidly that we hardly notice the ground shifting beneath our feet. It’s a trick of the metaphysical, an abstract notion of logic.

Imaginative play is also a trick of the metaphysical. In the story “Two Pairs of Eyes,” Ellen wakes up thirsty in the middle of the night but doesn’t want to get out of bed because she’s afraid of the “things” in the dark. She can’t see them or hear them, but she’s convinced they follow her. The lion tries to assure her there are no such “things,” but Ellen is adamant that she knows all about them.

“I know all about them,” said Ellen. “After all, I made them up in my head, didn’t I?”

“Ah,” said the lion. “I said there were no such things.”

“But of course there are,” Ellen said. “I just told you I made them up myself.”“Yes,” the lion said. “But—”

“So I should know, shouldn't I?” said Ellen.

This is the heart of the book. Ellen knows she is playing tricks with reality. By telling herself lies, she’s investigating the truth.

The imagination is enlarged by fiction—and fiction is just stories, and stories are just words, and words are just letters, and letters are just different kinds of marks (as Harold brilliantly illustrates). The imaginative world is very much a literary world—a time and place composed through sounds, words, and images. Barnaby, Ellen, and Harold are striking examples, but none of them tackle the complexity of this experience quite like Ann and Ben from Johnson’s Magic Beach.

After a series of successful Harold books, Johson’s editor, the legendary Ursula Nordstrom, asked if he’d be interested in writing a Harold “I Can Read!” book, a series intended for beginning readers. But instead of writing about Harold, Johnson found himself writing Magic Beach, his most poetic and elusive story.

The problem was it was too abstract for publishers. Even Nordstrom, a champion of strange children’s books wouldn't publish it. She felt it was too serious and difficult for children. But Johnson never gave up on the book. He referred to it as “far and away the best small thing I have done.”5

Eventually, in 1965, Holt, Rinehart & Winston published it but with a different illustrator, Betty Fraser, with the title Castles in the Sand. But Betty didn’t seem to get the story either, and the whole thing fell flat (and out of print). It wasn’t until Front Street published it in 2005 with Johnson’s original manuscript sketches that its true poetic brilliance was recognized.

Johnson’s biographer, Philip Nel, called it “Johnson’s most developed examination of the boundary between real and imaginary worlds…It is not so much a departure from his earlier work as it is a more finely tuned, carefully nuanced exploration of his favorite theme: the powers and limits of the imagination.”6

The story begins with Ann and Ben walking along a sandbar.

“I wouldn’t mind if we were in a story,” said Ann. “Because people in stories don’t go around all day looking for an old shell. Interesting things happen.”

“Nothing really happens in a story,” said Ben. “Stories are just words. And words are just letters. And letters are just different kinds of marks.”

To prove his point, Ben writes the word “jam” in the sand, but when a wave rolls up and washes the word away, it reveals a silver dish filled with delicious jam. The two of them write more words, and each time, a rolling wave presents them with words they’ve written.

Believing that such things only happen in “stories about magic kingdoms,” they write the word “king.” When a king appears, he’s disoriented and wonders whether he’s been under a spell the whole time or perhaps he’s under a spell now, Ann and Ben’s. (A clever play on the word “spell.”)

In order to help the king return to his throne, the two children write the words “city,” “castles,” and “horse” until an entire kingdom appears in the distance. They want to go with the king, but he orders them to stay. Before he leaves, he holds a shell to his ear and then hands it to Ben. It’s the shell they’ve been looking for, and Ben can hear the ocean inside it. But then he and Ann hear the real ocean; the tide is rushing in—there is no beach left to spell words in. They manage to escape up a tall hill and watch as the kingdom is swallowed up by the rising ocean.

Suddenly Ann stopped. “The story didn’t have a happy ending at all!” she said. “When we left it just stopped!”

She turned to Ben…But Ben had his ear to the shell, and he was listening to the sea.

The irony of this story is that it’s hard to put into words—its mystery eludes language. I’m sure Johnson would have no trouble compressing the complexity of Magic Beach into an elegant and precise explanation. (He was much smarter and more talented than I am.) But at the same time, maybe the story is his explanation. Magic Beach is an enigmatic narrative poem—a complex and carefully made object—that simultaneously creates and solves its own riddle. It’s not designed to teach this or that; rather it’s meant to be a fresh immersion in what is.7 It’s an immersion into art itself.

When I read Magic Beach—but also Harold, Barnaby, and Ellen’s Lion—I’m reminded of the insightful writings of the poet Jane Hirshfield (another artist much smarter and more talented than me). In an essay in Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry (1998), she writes:

“Immersion in art itself can be the place of entry… Yet however it is brought into being, true concentration appears — paradoxically — at the moment willed effort drops away… At such moments, there may be some strong emotion present — a feeling of joy, or even grief — but as often, in deep concentration, the self disappears. We seem to fall utterly into the object of our attention, or else vanish into attentiveness itself.

This may explain why the creative is so often described as impersonal and beyond self, as if inspiration were literally what its etymology implies, something ‘breathed in.’ We refer, however metaphorically, to the Muse, and speak of profound artistic discovery and revelation. And however much we may come to believe that ‘the real’ is subjective and constructed, we still feel art is a path not just to beauty, but to truth: if ‘truth’ is a chosen narrative, then new stories, new aesthetics, are also new truths.”

She goes on to explain the role of metaphorical language in writing and poetry:

“Great sweeps of thought, emotion, and perception are compressed to forms the mind is able to hold—into images, sentences, and stories that serve as entrance tokens to large and often slippery realms of being… Words hold fast in the mind, seeded with the surplus of beauty and meaning that is concentration’s mark.”

To me, Magic Beach is a metaphor for storytelling and imagination. Our imagination works with metaphor to take us beyond the places we have known. This is especially true for children. Through metaphors, children can hold big ideas and big feelings in their minds. And make-believe stories, whether in imaginative play or in books, often serve as the first entry point into metaphorical thinking.

In The Art of the Metaphor, Hirshfield explains:

“Metaphors give words a way to go beyond their own meaning. They are handles on the door of what we can know and of what we can imagine. Each door leads to some new house and some new world that only that one handle can open. What’s amazing is this: by making a handle you can make a world.”

A handle can make a world. So can a purple crayon or words in the sand.

Johnson’s books do what all great books do: they invite us to explore the great mysteries of life, where we’re free to look both inward and outward. Words strike against image in the transformative space between the real and unreal, expanding what we know and what we seek to learn.

Help support Moonbow (and me)

Writing these articles is tough and rewarding work. If my time, ideas, and research are valuable to you, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. If you love reading Moonbow, becoming a paid subscriber is the best way to show your support. It’s $5 monthly or $50 annually—or you can become a founding member—and pay any amount you want. If that’s not possible, sharing Moonbow and liking and commenting on articles are other great options.

With gratitude,

Taylor

Coming Soon: Moonbow Storytime

Picture books are performances. But even books that appear to be above picture-book age can benefit from being read aloud. Ellen’s Lion is one of those books—and I want to perform it for you. In my next post, I’ll read four of my favorite stories from the book out loud. I never thought I would sing on the internet, but never say never, I guess. Stay tuned!

More Moonbow

Interested in reading more in-depth articles on your favorite children’s authors? Check out Moonbow’s archive:

This piece would not have been possible without the incredible work of Philip Nel, Crockett Johnson's biographer.

I highly recommend his book, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children's Literature (2012), and his incredibly thorough website. His new book, How to Draw the World: Harold and the Purple Crayon and the Making of a Children's Classic comes out this October.

Questions to an Artist Who is Also an Author: A Conversation between Maurice Sendak and Virginia Haviland (1972)

Crockett Johnson’s Books: Collaborations, philnel.com

Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children's Literature by Philip Nel (2012)

A term coined by George Orwell

Afterword to Crockett Johnson's Magic Beach (2005)

Afterword to Crockett Johnson's Magic Beach (2005)

An Experiment in Criticism by C.S. Lewis (1966)

TAYLOORR! I loved it! And it made me want to dive into all of his books and the books about him. Your analysis of his work feels spot on. You always find the heart of the creator -- you have a gift for that and weaving together interesting things. I know this piece was challenging to craft, but it doesn't show -- you make posts like this look easy and they are NOT.

The only thing I would change is when you say you aren't as smart and talented as _____. I don't know ANYONE who can write literary criticism like you. You write with your heart and head at the same time -- it feels intellectual but never dry. Full of heart but never didactic. And like I said, you have a knack for getting to the soul of a book or a creator.

You're one of a kind! Can't wait for the next part!

1. You are incredible. Period, the end.

2. I NEED TO KNOW WHAT HAPPENS TO THE SKELETON FARMER! Please report back if you ever find out.