Stories Are to Share: 5 Ruth Krauss Books

(that shaped children's book author Carter Higgins)

Disclaimer: This is a picture-heavy newsletter. If you’re reading it in Gmail and see three gray dots while scrolling, please click them to see more. Maybe someday Substack will allow me to create slideshows, but for now, my newsletters will sometimes be cut off. Thanks!

Are you the same person you were when you were a child?

The writer Joshua Rothman asks this question in his recent New Yorker article “Being You.” It’s a question that begets more questions (which are the best kind). Are personalities fixed, or do they subtly change over time? Why are some of us so invested in our childhood experiences while others could care less? Do we have free will over our lives, or are we not responsible for our choices? Rothman writes that there are two opposing schools of thought on our relationships with our past selves: the continuers and the dividers. The continuers remember their past selves like it was yesterday; to them, life is a narrative, whereas the dividers are more removed and see their lives episodically. But people aren’t usually one-sided, and Rothman gives many examples in which we change and yet stay the same. This concept of double-being, of feeling connected to the past while being firmly rooted in the present, seems relevant to the creators of children’s books. Many of these artists appear to have a direct line to their childhoods. People often think children’s authors and illustrators are just big kids, but I’m not sure that’s the case, at least not for the best ones.

Ruth Krauss (1901-1993), author of over thirty books for children, is one of the best. Her books The Carrot Seed (1945), illustrated by her husband Crockett Johnson, A Hole is to Dig (1952), illustrated by Maurice Sendak, and A Moon or a Button (1959), illustrated by Remy Charlip, helped revolutionize picture books. Like Margaret Wise Brown, Krauss was a member of the experimental Writers Laboratory at Bank Street College, founded by Lucy Sprague Mitchell. Ruth followed the “here and now” philosophy, which maintained that children need stories anchored in the familiar world around them, and that plot should not be the driving force of a story. Krauss combined the playful and pragmatic language of children with her love of poetry and words to write books that are energetic, inventive, and timeless. Her kinship with children and with her own experiences as a child contributed to her lively style. But she’s sophisticated—her writing doesn’t only appeal to children. She, much like her work, maintains an alluring tension. Krauss isn’t a continuer or a divider; she’s both.

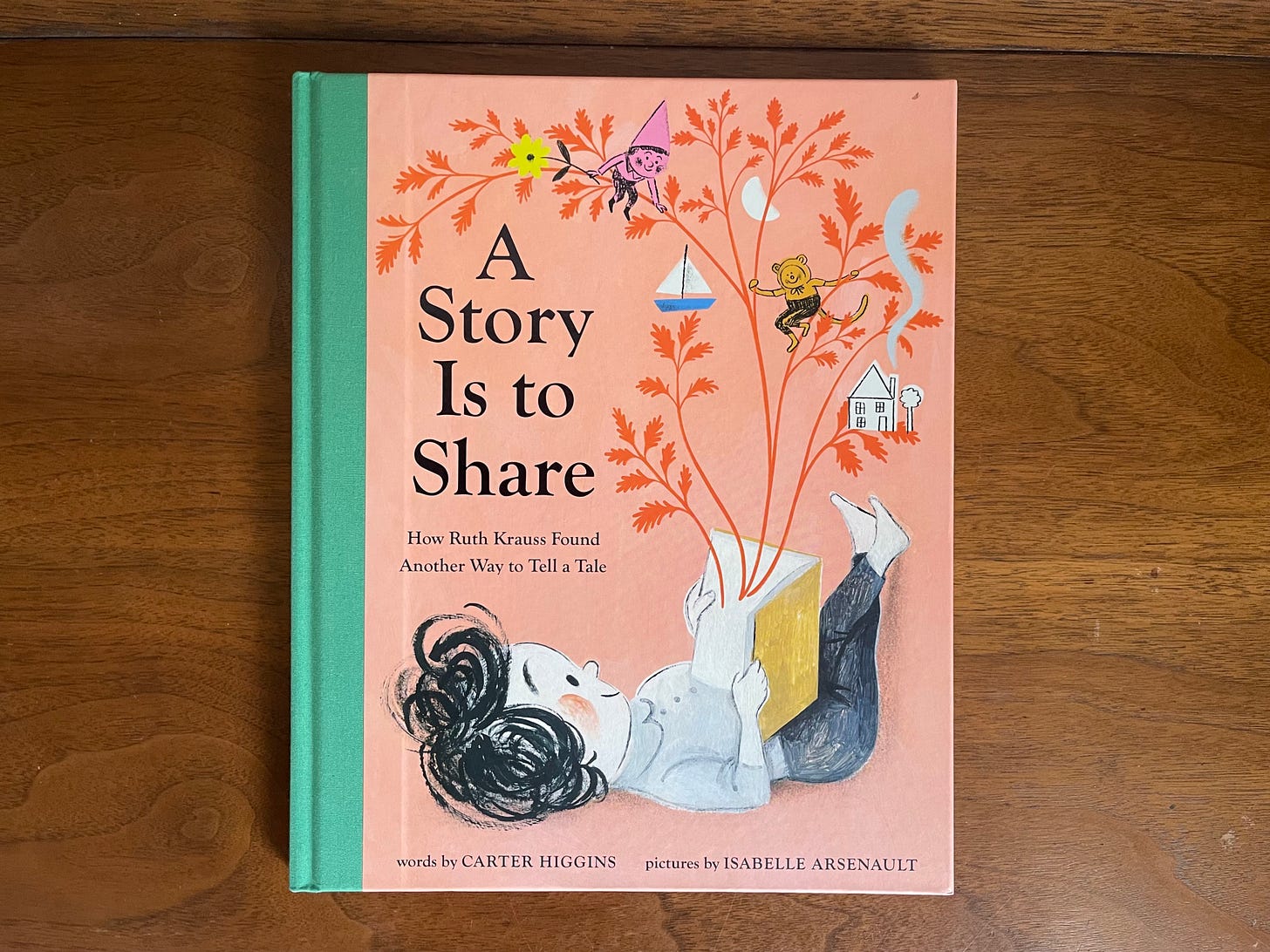

I fell in love with Krauss’s writing after reading her most famous book, The Carrot Seed. There are a lot of incredible picture books, but there aren’t a lot of perfect picture books—however, this is one of them. The Carrot Seed contains all of the elements of a great picture book (smart writing, rhythmic cadence, striking illustrations, and suspenseful page turns), but its most impressive narrative element is surprise. This book shocked me. Here’s a children’s book with a kid whose parents are wrong! A book with a kid who basically tells the adults to piss off because he believes in something regardless of what they think! How thrilling! Despite the spareness of words and pictures, this book is full of life—quite literally, since the carrot seed grows into a big, thriving carrot (spoiler)! It’s a book you’ll never forget, which is why I’ve wanted to feature it and so many other Ruth Krauss books on Moonbow. But I wasn’t sure how to go about it until I learned that the talented author Carter Higgins wrote a picture book about Krauss, A Story Is to Share: How Ruth Krauss Found Another Way to Tell a Tale (2022), illustrated by the incredible Isabelle Arsenault. I’m excited to have Carter on Moonbow! Carter shares more about the fascinating perplexities of Ruth Krauss, and she gives us a peek into her new book—a beautiful tribute to Krauss’s exuberant creativity. I also asked her to share five Krauss books that shaped her and inspired her to write this story.

Here’s Carter:

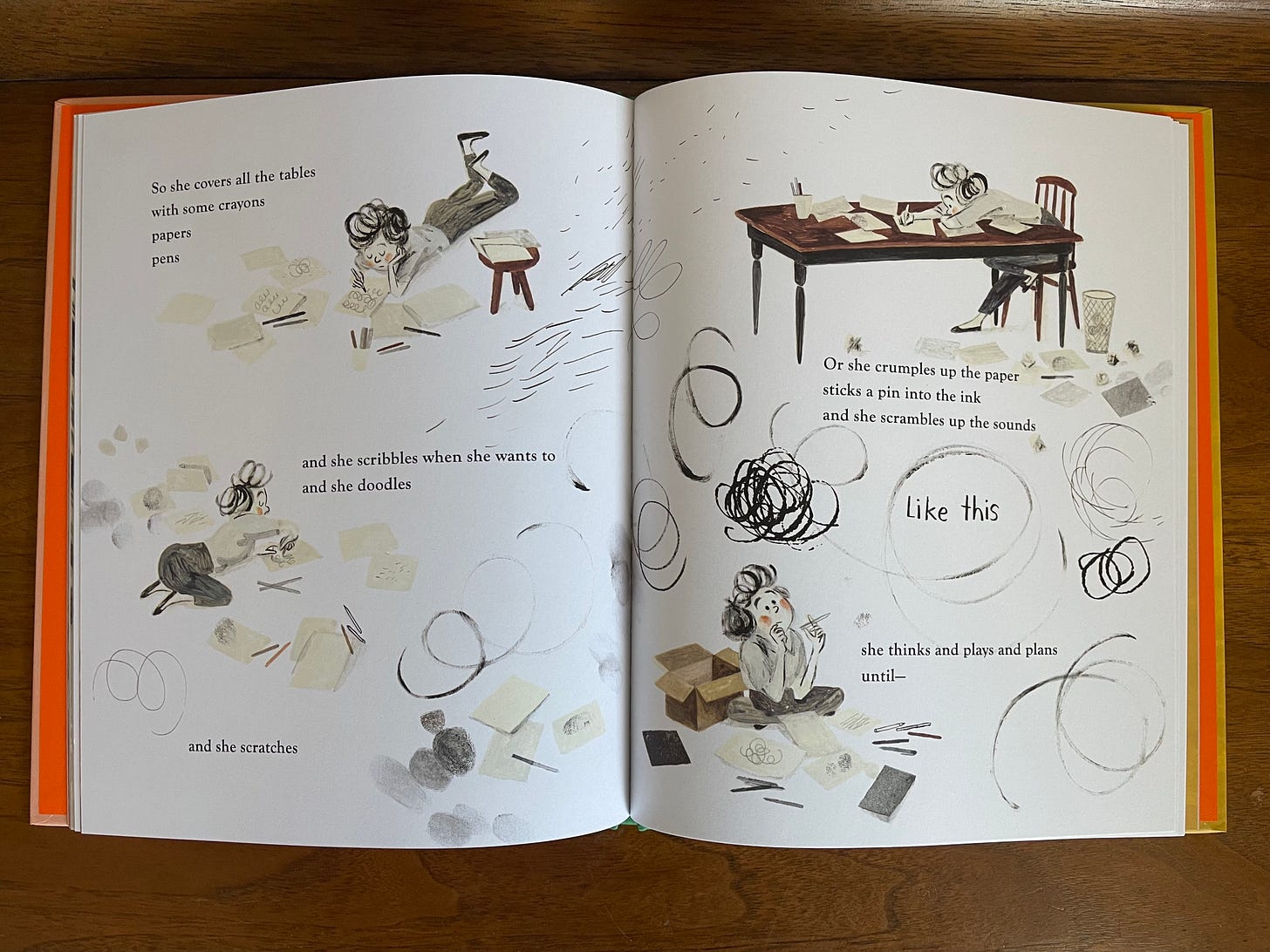

A Story Is to Share: How Ruth Krauss Found Another Way to Tell a Tale is just that—a look at all of the ways an extraordinarily creative person lived and worked and told stories through it all.

You don’t need to be an expert in the history of children’s literature to appreciate her process, to see like she does, to play like she does. We’ve created a portrait of her, one that hopefully feels up close and personal, but one you still have to squint at in order to understand. It’s an impossible task, writing an homage to a storytelling hero. I think we’ve done so with our utmost respect while maintaining a little mystery.

Is being a child at heart an exceptional way to live a creative life? I think so, yes, and I think Ruth might agree. Or maybe she wouldn’t and she just was instead. I’m not sure. Even after immersing myself in her life and impressive canon, she remains a bit elusive to me. I imagine she’d like it that way.

Here’s a stack that has shaped me–both as a writer and a reader (and probably a human in the world).

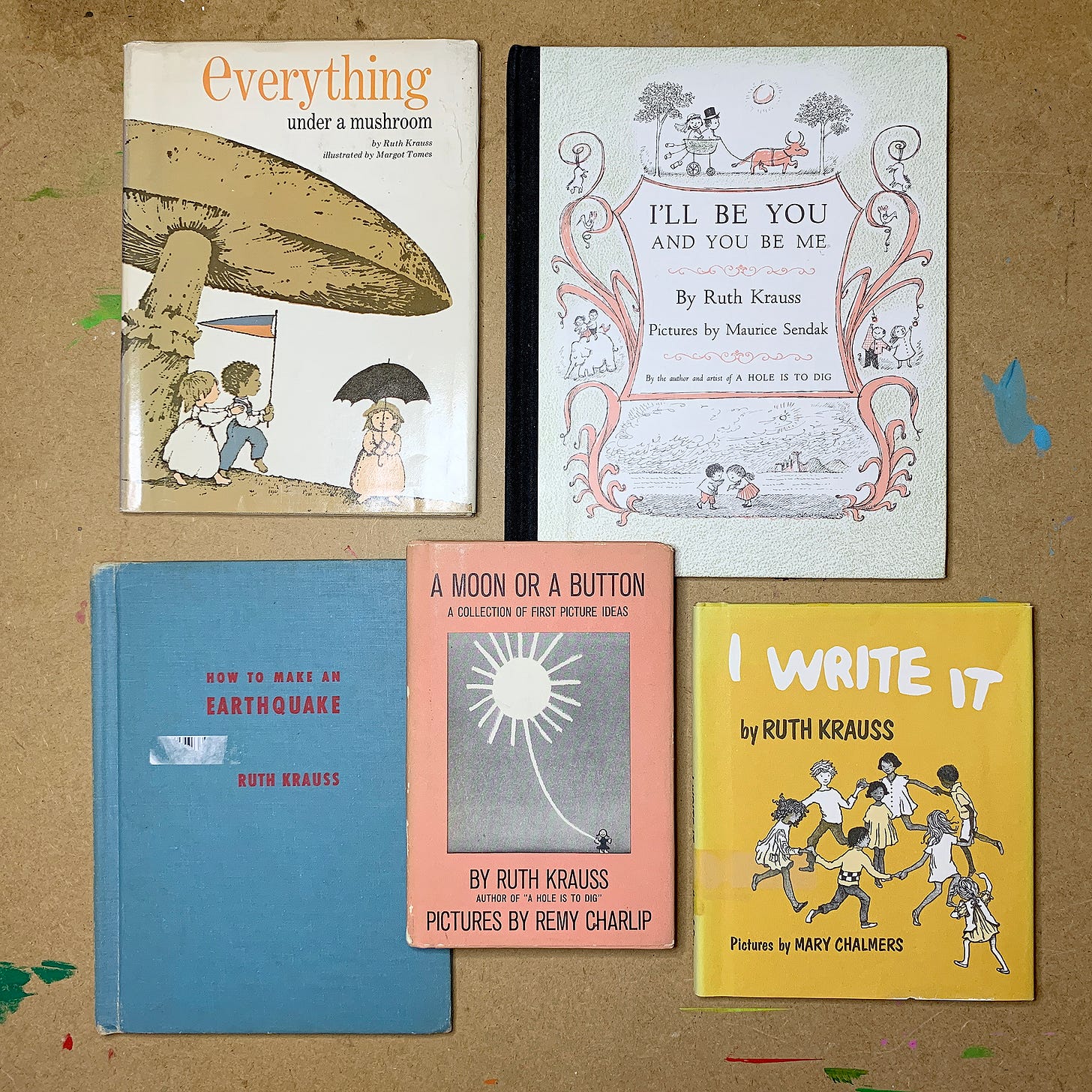

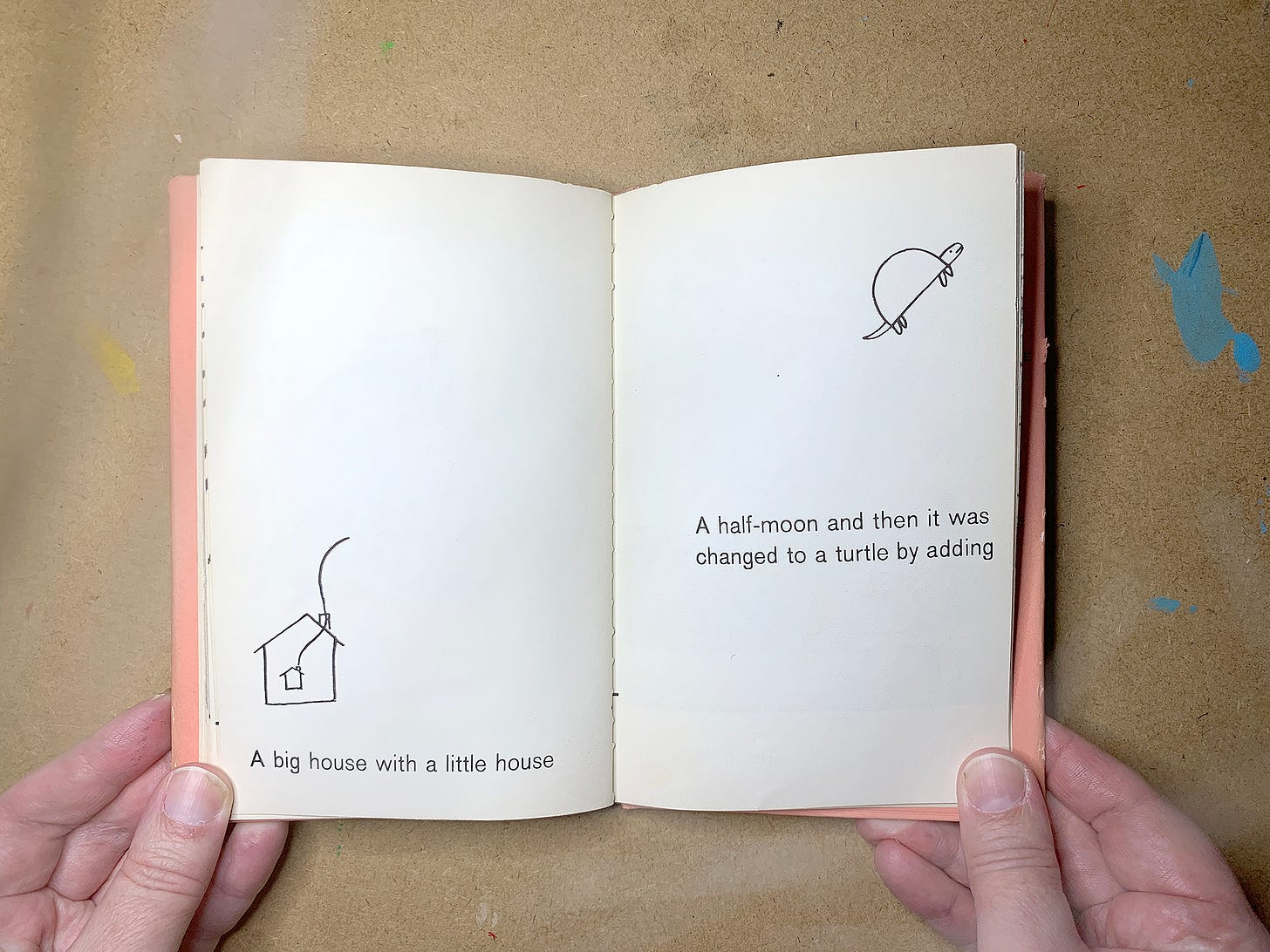

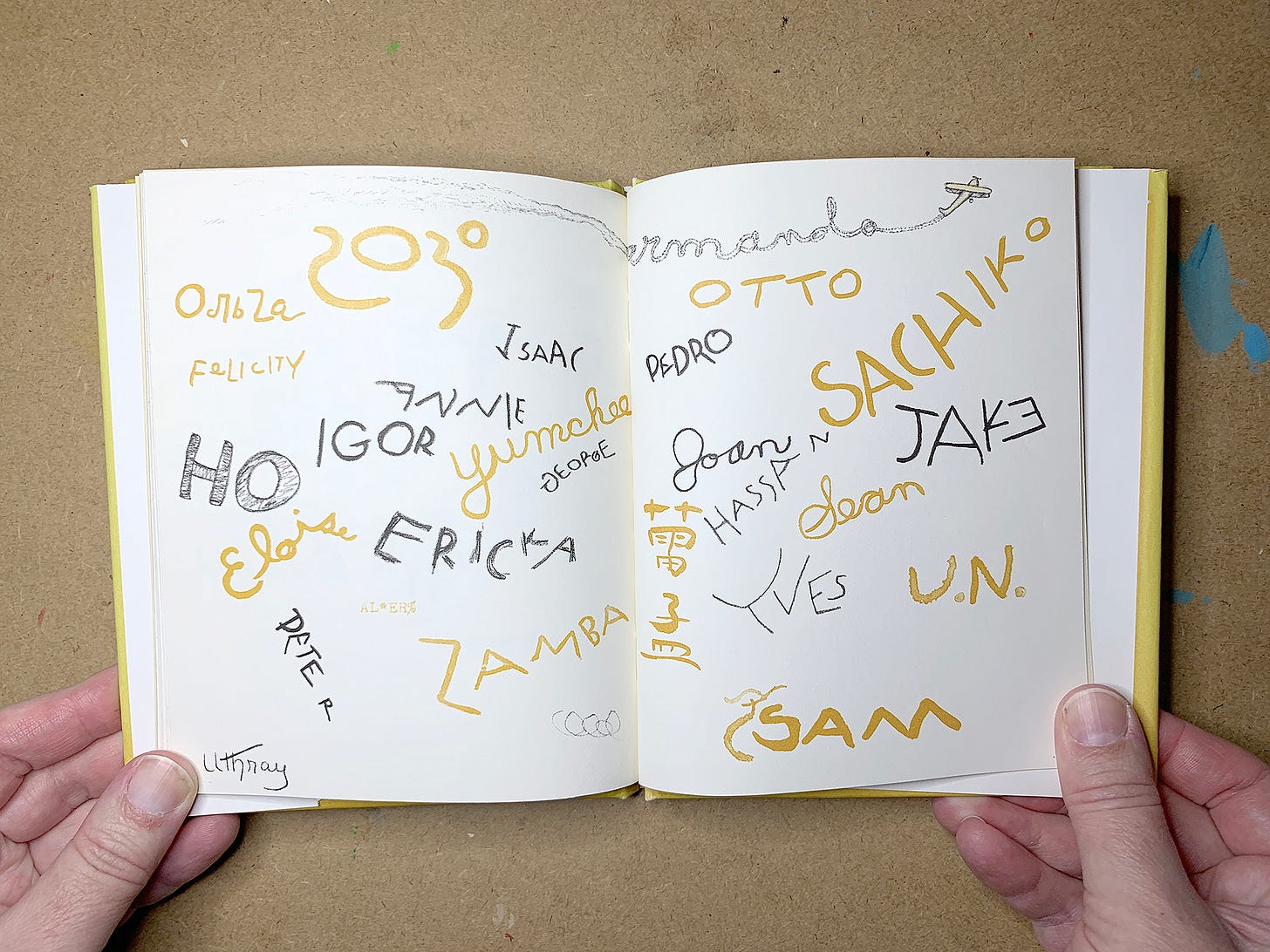

A Moon or a Button: A Collection of First Picture Ideas, pictures by Remy Charlip (1959)

It seems so simple, and yet. What is that thing you see? What if it’s something else? Any good picture book maker would agree that a fresh perspective and immersing someone in your made-up world is essential. And here, there’s no place else to go besides there with Ruth and Remy. This book is a tiny representation of what picture books do best: be an end and a beginning all at once.

(And honestly, there’s no Circle Under Berry without this concept of ‘picture ideas’ at its core.)

I Write It, pictures by Mary Chalmers (1970)

Ok, I confess picking up this particular used library copy because some elementary school prankster had added a well-placed ‘sh’ on its first page: On a piece of paper I write <AHEM> it.

This book is doing gigantic work by staying small. This seems to be the connective thread in Ruth’s books, and why they are so kid-centered without ever being condescending. Kids’ inner worlds are just that: small but big

I Write It takes its time to reveal what it is, meandering through fantastical and everyday routines. There’s a connectivity to the cast of kids inside–everyone seems to understand and hold this thing in high regard. So what is it?

Something sacred, something gifted, something entirely theirs.

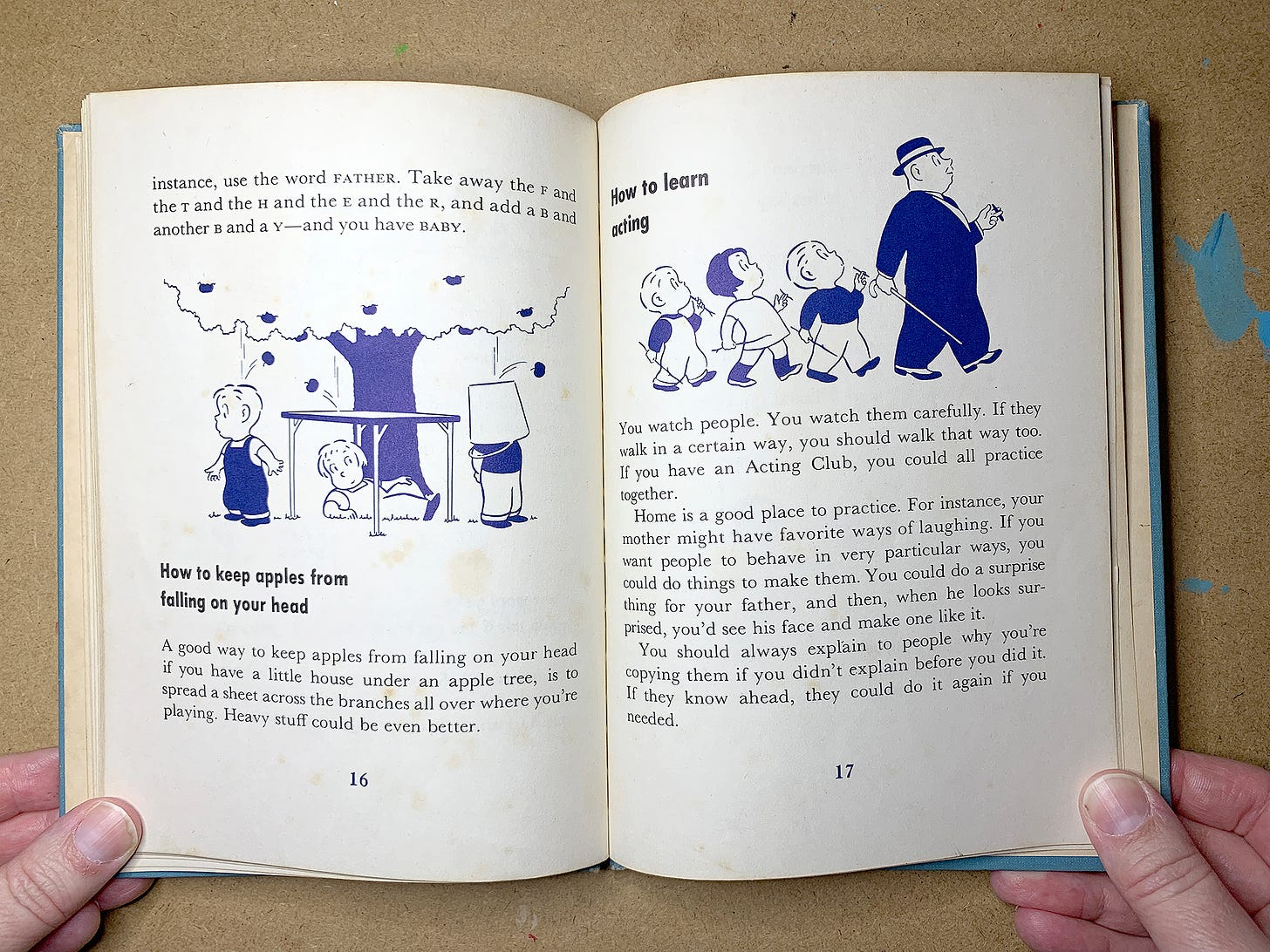

How to Make an Earthquake, pictures by Crockett Johnson (1954)

This is the ultimate activity guide. Pardon the pun, but is it groundbreaking even? It isn’t your usual Step 1, Step 2, ta-da! This is ‘how to make a mish-mosh’ and ‘how to make guests think they’re going to swallow bugs’ and ‘a good way to carry your carrots’ and ‘walking with crumbs.’

So much of my research into Ruth’s life confirmed to me that she was an expert at remembering childhood. And maybe not just remembering it, but continuing to exist as a big kid? This book celebrates humongous, expansive, triumphant ideas—ideas I imagine look random, floaty, or a half-baked pile in disarray to most grownups.

I think Ruth would say yes, exactly.

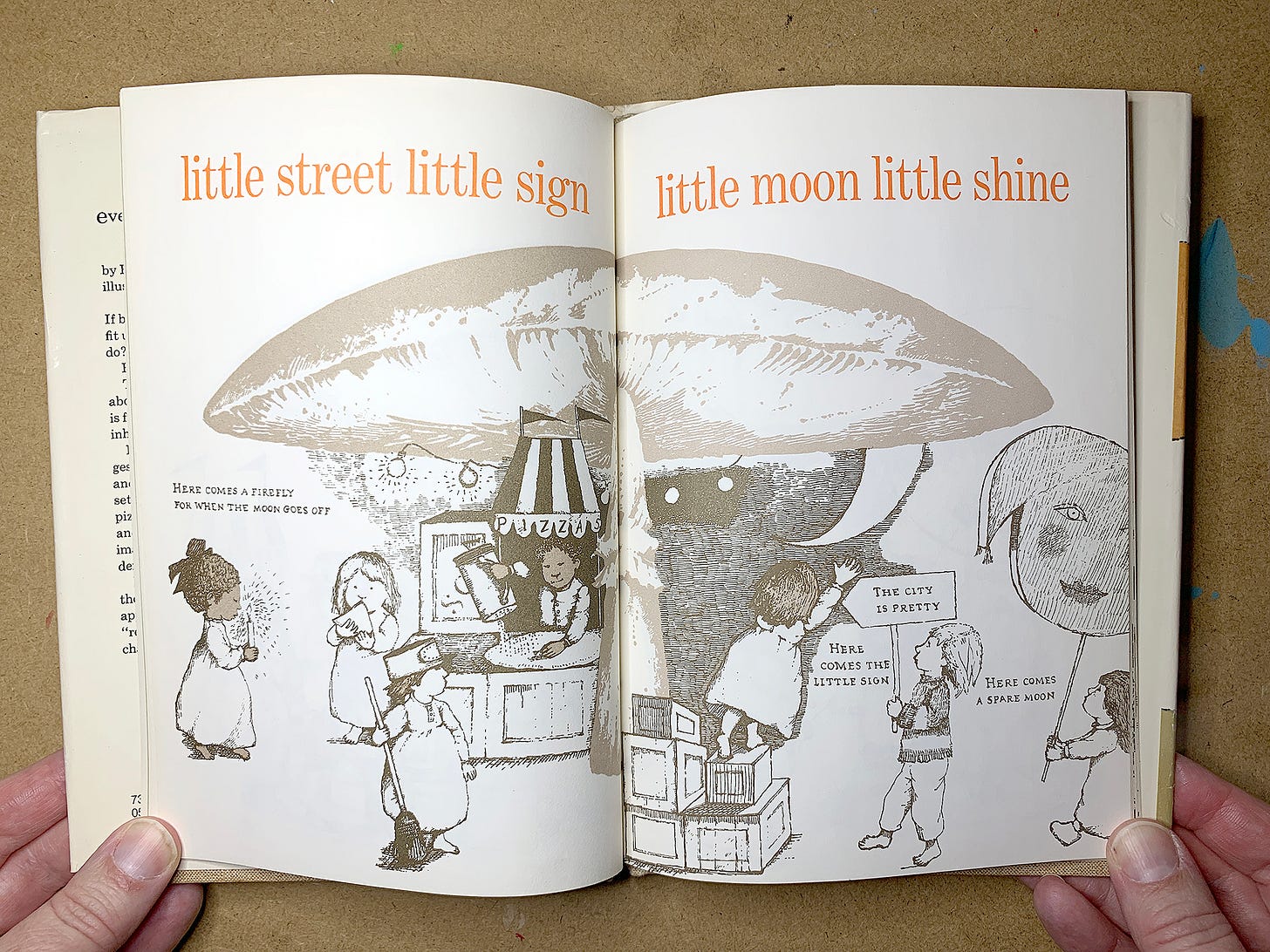

Everything Under a Mushroom, pictures by Margot Tomes (1973)

If a diorama was a book, this would be it. If a diorama had a recording device that captured the way kids play make-believe inside that diorama? Even better. And luckily, a poet like Ruth set up this stage play, epic and miniature and completely in tune with the way kids’ brains work.

Are kids the original improv actors? This delightful little yarn is ‘Yes, and. . .’ that fits in your hand.

(Did I name Everything You Need for a Treehouse as an homage of sorts? Yes, I did.)

I’ll Be You and You Be Me, pictures by Maurice Sendak (1954)

Each book in this small stack holds loosely to narrative, and this quality is particularly on beautiful display here. Picture books are perfect vehicles for getting a little weird, a little fragmented, and a little all over the place. Don’t kids do the same? Wouldn’t we all do well to remember that as grownups?

These charming vignettes are never chaotic. There’s logic if you look close. Is it a moon or a button or a fully fleshed-out story, right in the corner of a page?

Making a book about Ruth Krauss meant honoring her system of logic and its playful spirit, its insightful way of remembering, and its authentic awe of who the book is for–and in our case who it’s about. I hope it’s a celebration of a wildly creative life.

Thanks for sharing, Carter!

Carter Higgins is the author of Everything You Need for a Tree House (2018), illustrated by Emily Hughes, Circle Under Berry (2021), which she wrote and illustrated, the “Audrey L & Audrey W”(2021-2022) series, illustrated by Jennifer K. Mann, and other great books for kids! You can learn more about her books at www.carterhiggins.com.

“Krauss books can be bridges between the poor dull insensitive adult and the fresh, imaginative, brand-new child. But of course that only will work if the dull adult isn’t too dull to admit he doesn’t know the answer to everything. Krauss books will not charm those sinful adults who sift their reactions to children’s books through their own messy adult maladjustments. That is a sin and I meet it all the time. But there are some adults who don’t sift their reactions to children’s books through their own messy adult maladjustments and I guess those are the ones who will love and buy Krauss.”

— Ursula Nordstrom (1910-1988), acclaimed children’s book editor

Recommended reading: Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom (2000), collected and edited by Leonard S. Marcus.

Moonbow is a reader-supported publication. It exists because of the support of generous readers like you! If you enjoy Moonbow, the best ways you can support it is to subscribe, share this newsletter with a friend, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Thanks for reading!

So glad you linked to this post! Loved it ❤️

That was an interesting article you shared about continuers and dividers... I think I’m more of a continuer because I do feel connected to my childhood (a lot of my tastes in movies and books are the same, and I’m always drawn to certain types of narratives and themes). I suppose that’s a good thing since I’m working on some children’s stories right now 😄 Even though I’ve changed over the years, I can still can recognize aspects of myself that have remained the same.