Not long ago, I took a walk to clear my mind, but instead of listening to my thoughts, I listened to Ali Smith. Smith is a brilliant contemporary author who, as one New York Times critic put it, “has a beautiful mind,” so I was in good company. Smith talked about art and how it provokes and “unfixes” us—that “art opens a hole in that fixity” and creates space for us to question things we think we know. She believes curiosity fuels connection, engagement, and aliveness. The idea that art has the power to radically alter fixed forms immediately made me think of one of my favorite artists, Remy Charlip.

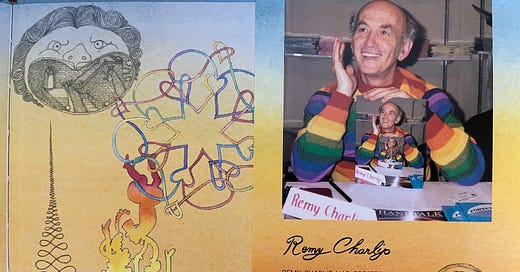

Remy Charlip via Remy Charlip Estate (text by me)

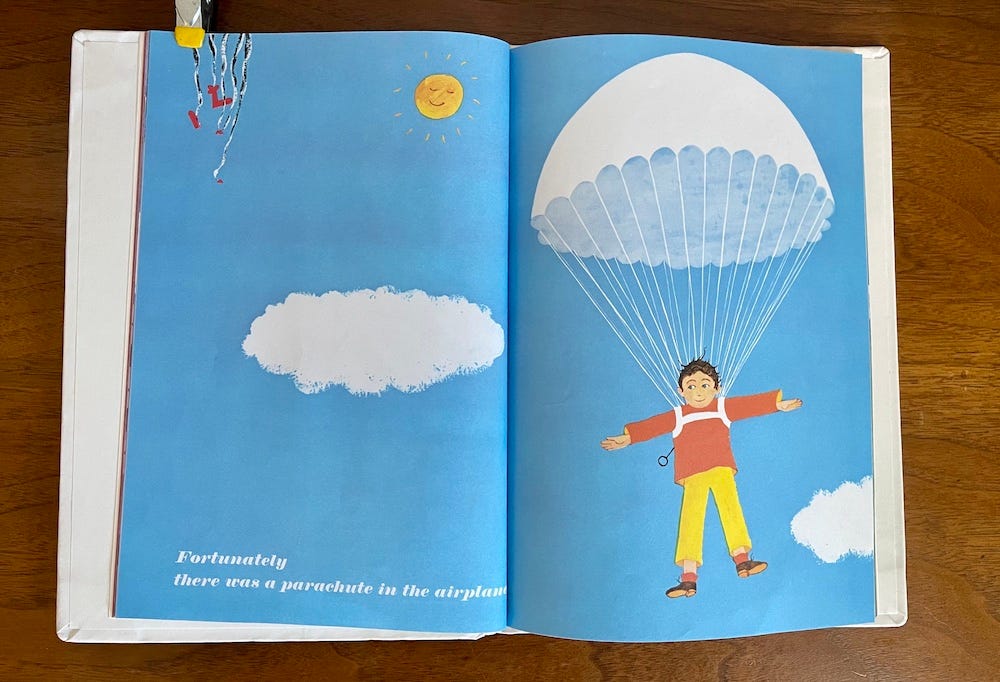

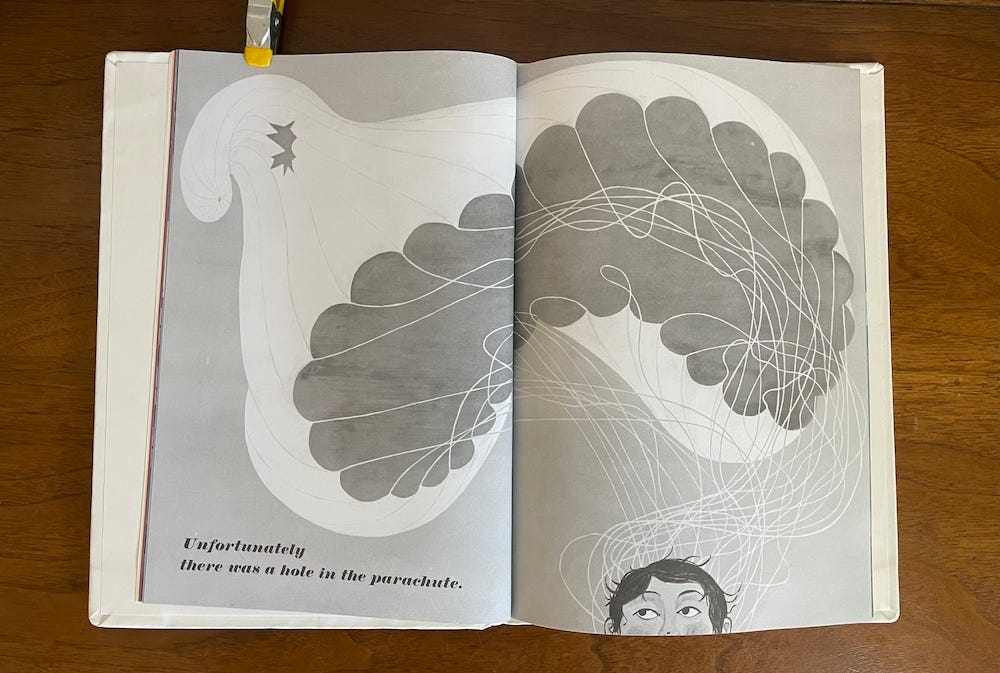

Remy Charlip was a dancer, choreographer, designer, and teacher, but I know him best as a children’s book author and illustrator. I can’t remember when Charlip’s books first entered my world, but I remember the feeling I had when I first read what is now his most famous book, Fortunately (1964). It was exhilaration, not only for its silly humor but in anticipation of what wild surprise would come next. The story is about a boy named Ned, who receives an invitation to a surprise birthday party in Florida, but he’s miles away in New York; fortunately, he has an airplane; unfortunately, the motor explodes; fortunately, he has a parachute — and so begins a series of chaotic mishaps for Ned. The repetition and contrasting spreads in vibrant color and back and white propel the reader in every direction as Ned’s luck changes. ''It is a flying, falling in space, diving in water, swimming, running, digging himself in and out of a cave and into a ballroom dance,'' Charlip told The New York Times in 1999.

Fortunately (1964)

It was while reading Fortunately that I recognized the power of the page turn. The anticipation builds with each turn of the page: Will poor Ned be eaten by a ferocious tiger? Knowing it’s a book for children, it’s unlikely, but there’s still a chance—and you can’t wait to flip the page to find out. Turning a page in a Charlip book is like opening a door, not to some fantastical far-off land, but to new experiences where pictures and words dance together unexpectedly.

Listen to “A Page Is a Door,” by Remy Charlip, read aloud by me.

Remy Charlip’s approach to art was democratic and experiential. To him, there were no boundaries between choreography, dance, and picture books. He recognized the fluidity and suppleness between the forms. Both dance and picture books speak in visual narratives, and both can be interpreted in various ways depending on the audience. As a choreographer, Charlip challenged his pupils to think outside the box, often encouraging them to transform limitations into opportunities. He believed any body could dance. In “Remy Charlip’s Imaginary Dances,” for MOCA-LA’s 1984 radio series The Territory of Art, Charlip recalls when he first decided to become a dancer, he thought it meant he had to dedicate his entire life to the practice, but as he got older, he realized that every moment in our ordinary lives could be considered a dance: sleeping, reading, eating, winking — life’s one big dance! Once he recognized this, his entire approach to art changed.