I’ve never been able to keep a diary. My best efforts were from around 1999-2000, when, at 17, I found myself entangled in a love triangle. It was my first bittersweet taste of love, and writing helped me digest the strange mixture of feelings I was experiencing. Still, even then, my entries were brief and inconsistent. Twenty-five years later, it’s no different. The pages in the notebooks I bought at the start of the year are mostly blank, aside from random quotes I want to remember or scribbled grocery lists. Maybe this is intentional. Maybe I don’t want a clear picture of how I felt over the course of a year. It always ends with the same boring realization: I had my ups and downs.

That said, piecing together my fragmented notes and research from this past year isn’t entirely worthless; it’s actually kind of revealing. I can see the stories, sights, and sounds that shaped me. They’re not explicitly personal, and yet they’re incredibly personal. Most of my notes are about other people: art they created, something they said, a book they recommended. They’re like shimmering shards of glass, an unrecognizable mess of broken pieces, but if you look closely, you can see your reflection staring back at you.

It reminds me of something the writer Doreen St. Félix recently wrote in her piece on James Baldwin for The New Yorker, “You think, poring over his letters, that you are getting to know him better—the uncovered lover, et cetera—when the person you are getting to know better is yourself.”

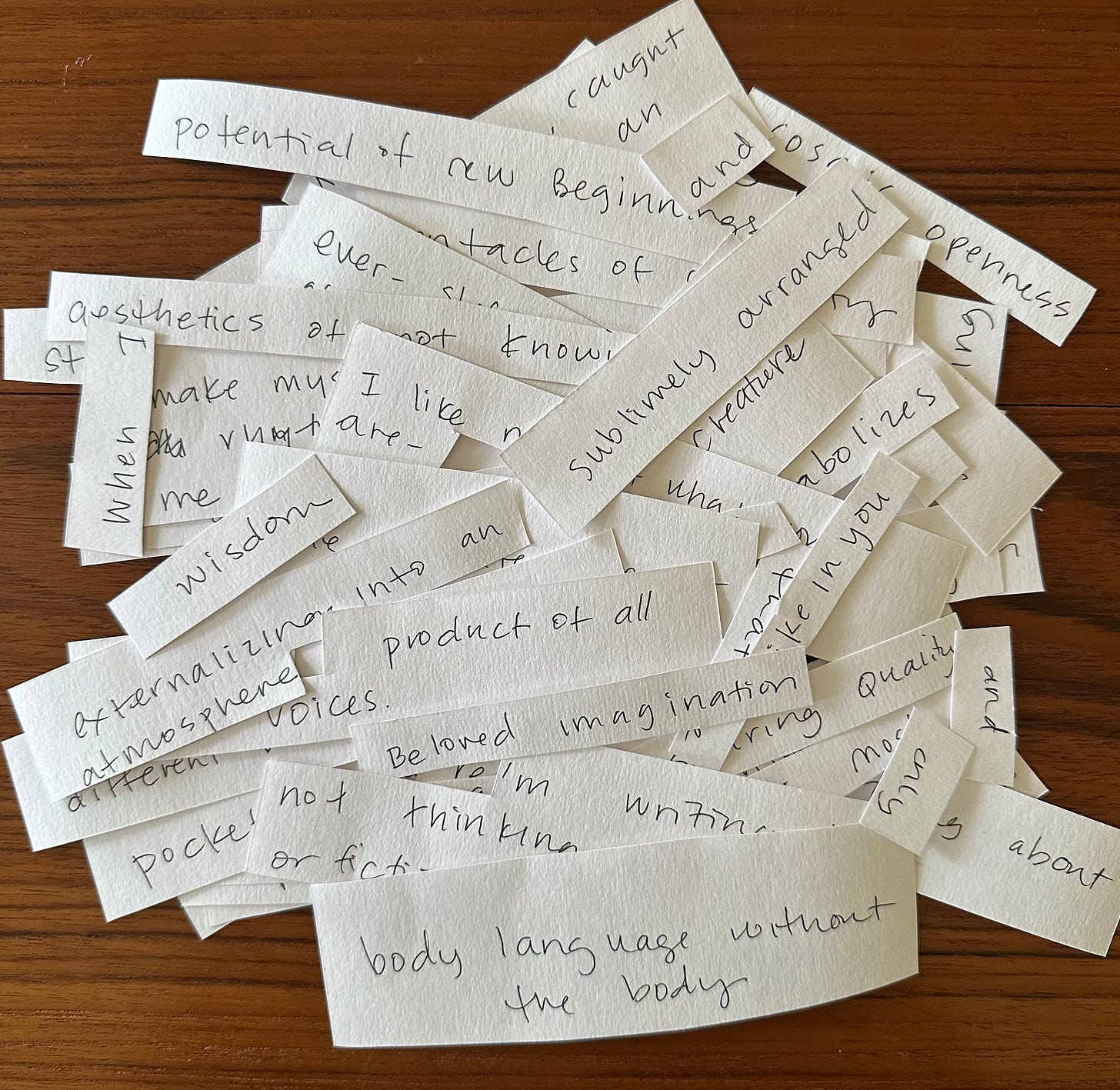

This got me thinking. What would happen if I tried to turn these fragments into a William S. Burroughs-style cut-up?1 David Bowie used to do this. He would cut up and randomly rearrange diary entries, quotes, and lines from books to see what they might reveal about his life.

In a 1970s video clip, he talked about his process:

“What I’ve used it for, more than anything else, is igniting anything that might be in my imagination. It can often come up with very interesting attitudes to look into. I tried doing it with diaries and things, and I was finding out amazing things about me and what I’d done and where I was going …If you put three or four dissociated ideas together and create awkward relationships with them, the unconscious intelligence that comes from those pairings is really quite startling sometimes, quite provocative.”

I decided to try, not randomly, but with intention. I cut up and rearranged memorable quotes, phrases, and bits of language that I jotted down throughout the year. I spoke them out loud, listening to the words, hearing which ones wanted to sit next to each other and which ones wanted to be left out.

Bowie was right; it is interesting. I can see my preoccupations, the restless searcher in me. And I’m not surprised that this collection of phrases worked well together—many are about the imagination, pulsating energy, and being open to ideas, sensations, and the unexpected. But reading my cut-up made me a little sad. I started 2024 with an open heart but lost it along the way. Does that happen every year? To everyone? Probably. Times are hard for dreamers. But this exercise was weirdly therapeutic, much more so than reflecting on my year and planning goals for the next one (boring!). The results are mysterious and, like Bowie said—provocative. It could mean nothing, but it could also mean everything.

2024

Potential of new beginnings

the aesthetics of not knowing

tentacles of curiosity

ever-shifting microclimates of mood

sublimely arranged

I’m just trying to make sentences that excite me

A writerly ecstasy, caught and passed like an electric charge

a cosmic openness

flashes of awareness

feeling of rapture

hypersonic delirium

strange frequency

and

sensation

metabolizes

and

seeps into my bones

The marvelous is

fleeting and enduring

blink and you might miss

what the deepest currents are

When I make myself receptive to the rhythm and forms about me

it’s not about my mind

but my

shock-receiving capacity

the absolute form of imagination

All consciousness is a kind of storytelling and invention

externalizing into atmosphere

a vector for all these different voices and influences

an instrument of transformation

separate and the same

a pocket universe inside of you

It’s not a dictionary word but a magic word

bizarre and beautiful

reality colors it

a syntax for life

body language without the body

conveys something about being alive

I am good

but

there must be fire

Most of these fragments are from things I read or listened to while working on pieces for Moonbow. If you had told me five years ago that writing about children’s books would involve me reading Gertrude Stein, Immanuel Kant, Jonathan Swift, Marina Warner, Virginia Woolf, André Jolles, Italo Calvino, Sheila Heti, June Jordan, Angela Carter, George Saunders, Diane Williams, Helen Oyeyemi, (the list goes on), I would have never believed you. I was naive. I didn’t know how complex and sophisticated these “simple” texts can be. Children’s books—like books for adults—are products of intertextuality. They’re rich in symbolism and meaning. You don’t have to recognize the references and allusions to enjoy the books, but it can enhance the experience.

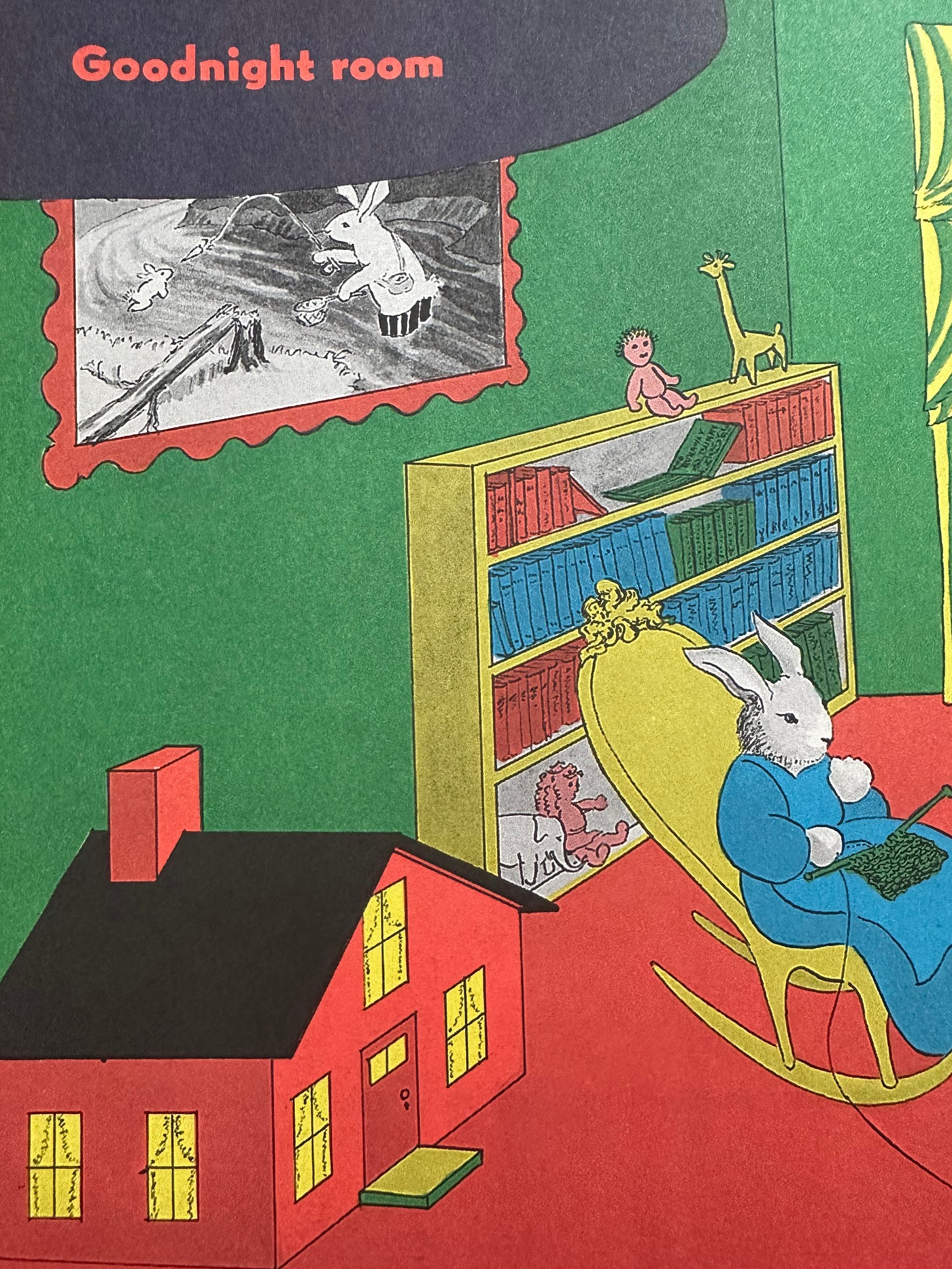

Even children delight in discovering hidden references—like Clement Hurd’s illustrations of The Runaway Bunny (1942) book in the bunny’s room in Goodnight Moon (1947), or the frog doll on Imogene’s bed in Imogene’s Antlers (1985), a nod to David Small’s first book, Eulalie and the Hopping Head (1982). The point is to pay attention. Read widely and deeply. Search for clues. Even if they mean nothing to most, they mean something to you. This is the art of noticing, the art of reading.

These fragments influenced these Moonbow articles:

Thank You

Thank you for reading and supporting Moonbow in 2024. I like to experiment with the types of articles I write. It keeps me motivated and excited about this space (when I’m increasingly disillusioned by all content/social media platforms), and it’s wonderful to be a part of a community that’s game for anything. Here’s to more of that in 2025!

All writing is in fact cut-ups. A collage of words read heard overhead. What else? Use of scissors renders the process explicit and subject to extension and variation. Clear classical prose can be composed entirely of rearranged cut-ups. Cutting and rearranging a page of written words introduces a new dimension into writing enabling the writer to turn images in cinematic variation. Images shift sense under the scissors smell images to sound sight to sound sound to kinesthetic. This is where Rimbaud was going with his color of vowels. And his ‘systematic derangement of the senses.’ The place of mescaline hallucination: seeing colors tasting sounds smelling forms.” —William S. Burroughs, ‘The Cut-up Method of Brion Gysin”, in William S. Burroughs / Brion Gysin, The Third Mind, Grove Press, New York, 1982

INTERVIEWER

You deplore the accumulation of images and at the same time you seem to be looking for new ones.

BURROUGHS

Yes, it’s part of the paradox of anyone who is working with word and image, and after all, that is what a writer is still doing. Painter too. Cut-ups establish new connections between images, and one’s range of vision consequently expands.

—William S. Burroughs, The Art of Fiction No. 36, The Paris Review, 1965

I love this exercise — and what a poem it created! Feels like the perfect keepsake to capture the year’s enthusiasms.

I've never been able to keep a diary, either! Your fragments make a beautiful collage. Thank you for sharing!