The more I look at Wanda Gág’s lithographs, the less I see them. Or maybe it’s not that I’m seeing too little, but too much? To fully appreciate her prints requires a shift in perspective. It’s like looking at one of those Magic Eye illusions; stare too hard, and the image remains flat, but if you look closely and loosely, at the same time, it starts to stretch, the edges soften, while the center sharply comes into focus. It pulls your vision into its core, then right past it, where something new, something that was once hidden, is revealed. No magic glasses are required. You create the image yourself. But to get beneath the surface, your vision must be supple enough to bend freely without breaking; it needs to be pliable.

Children are born with pliable vision. Their lenses are more flexible, allowing them to focus on objects both close up and far away, but as they age, their lenses become rigid, and they lose their ability to change shape and adapt. Children literally see things differently. But it’s not just their vision. They also hear, feel, and experience the world differently than adults. They are richly sensuous and more rhythmically attuned to the world around them. For children, even commonplace objects possess idiosyncratic beauty (just watch them marvel at a cardboard box to see what I mean). Because of their flexible mindset, children are more comfortable stretching their imaginations between the ambiguous space of reality and fantasy. This is why I like reading children’s books; they help me see the world from a child’s perspective and make my vision less rigid—at least metaphorically.

I especially like reading fairy tales. One of my favorite writers, Sabrina Orah Mark, said “I don’t know if you’ve ever held a fairy tale in your hand, but it has this amazing pliability. Try to stretch it from your childhood all the way to where you are standing right now. See? Isn’t that amazing?”1 Fairy tales and the oral tradition of storytelling—stories told to children in the dark, before bed, have, as Mark suggests, “a fluidity, are bodiless in certain ways or at least the borders are a little bit more blurred…and because of that blurring, it does make the story itself, the mode of storytelling, or the way that it enters the body that much more powerful, and also much more dangerous because you can’t contain it. It’s a kind of wind, it’s a kind of air that we breathe, that we share.” 2

In all children’s stories sound is important, but especially in fairy tales. Mark explains, “fairy tales and children’s stories like nursery rhymes, like songs, like prayer, like spells, like poetry, are all intricately connected, they feel very intended for the ear…if you think about the stories you were told as a child, not the stories you had read, but the stories that were told to you, like don’t they get into your bones in a way that’s very different than let’s say, a story you read online, even if it’s the same story?” 3

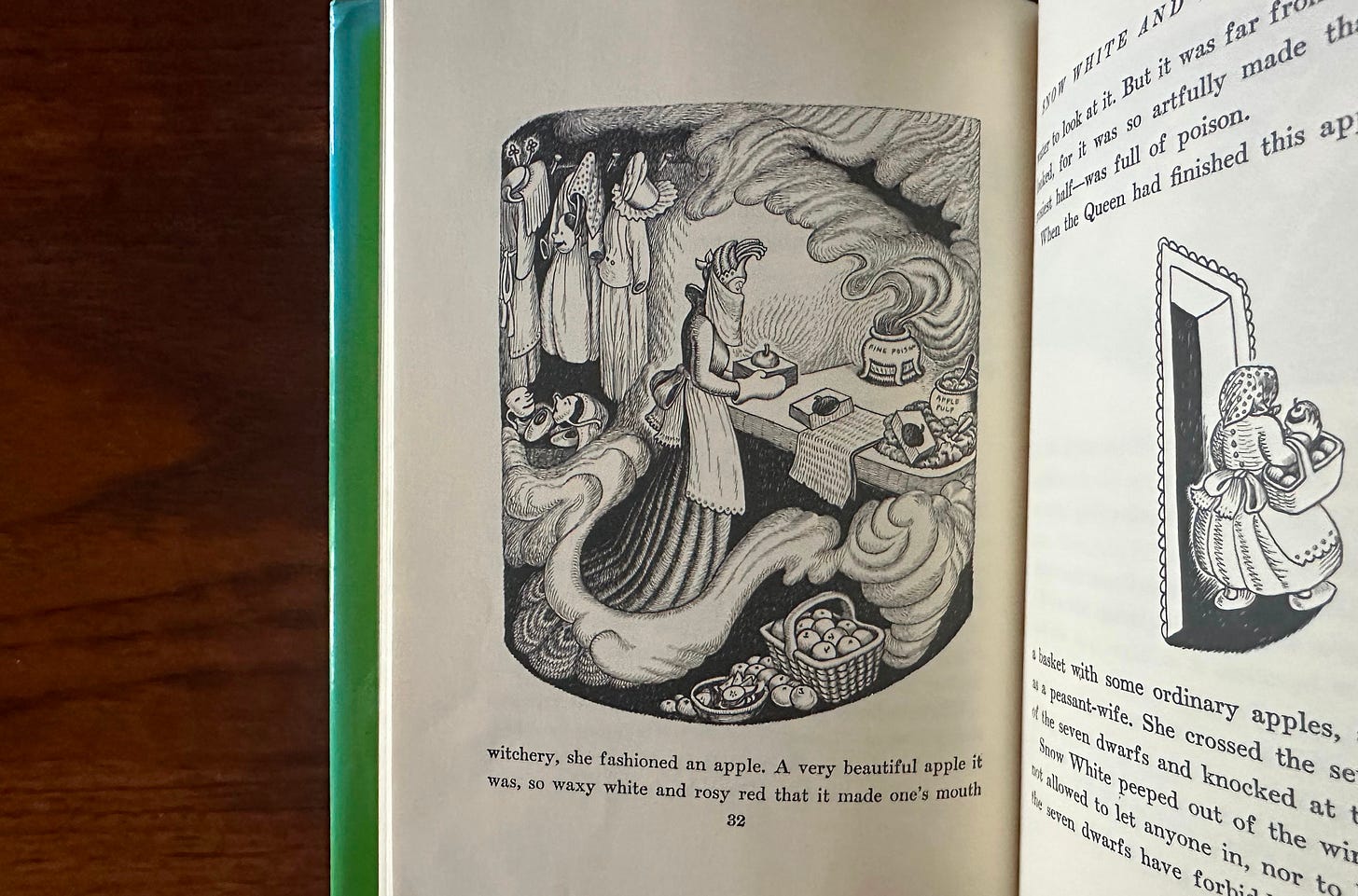

In Wanda Gág’s introduction to Tales From Grimm (1936)—a set of Grimm’s fairy tales she freely translated and illustrated—she writes about the profound bodily experience of hearing these stories read out loud to her as a child:

“The magic of Märchen is among my earliest recollections. The dictionary definitions—tale, fable, legend—are all inadequate when I think of my little German Märchenbuch and what it held for me. Often, usually at twilight, some grown-up would say, ‘Sit down Wanda-chen, and I’ll read you a Märchen.’ Then, as I settled down in my rocker, ready to abandon myself with the utmost credulity to whatever I might hear, everything was changed, exalted. A tingling, anything-may-happen feeling flowed over me, and I had the sensation of being about to bite into a big juicy pear.”

Wanda Gág didn’t just breathe in the air of these stories; she devoured them.

But before Tales From Grimm, there was Millions of Cats (1928), Gág’s first book for children and arguably the first-ever picture book. At the time, Gág’s lithographs were gaining success in the fine art world. Her distinctive style caught the attention of the editor Ernestine Evans, who believed Gág had the talent and ingenuity to revolutionize children’s books. She was right.

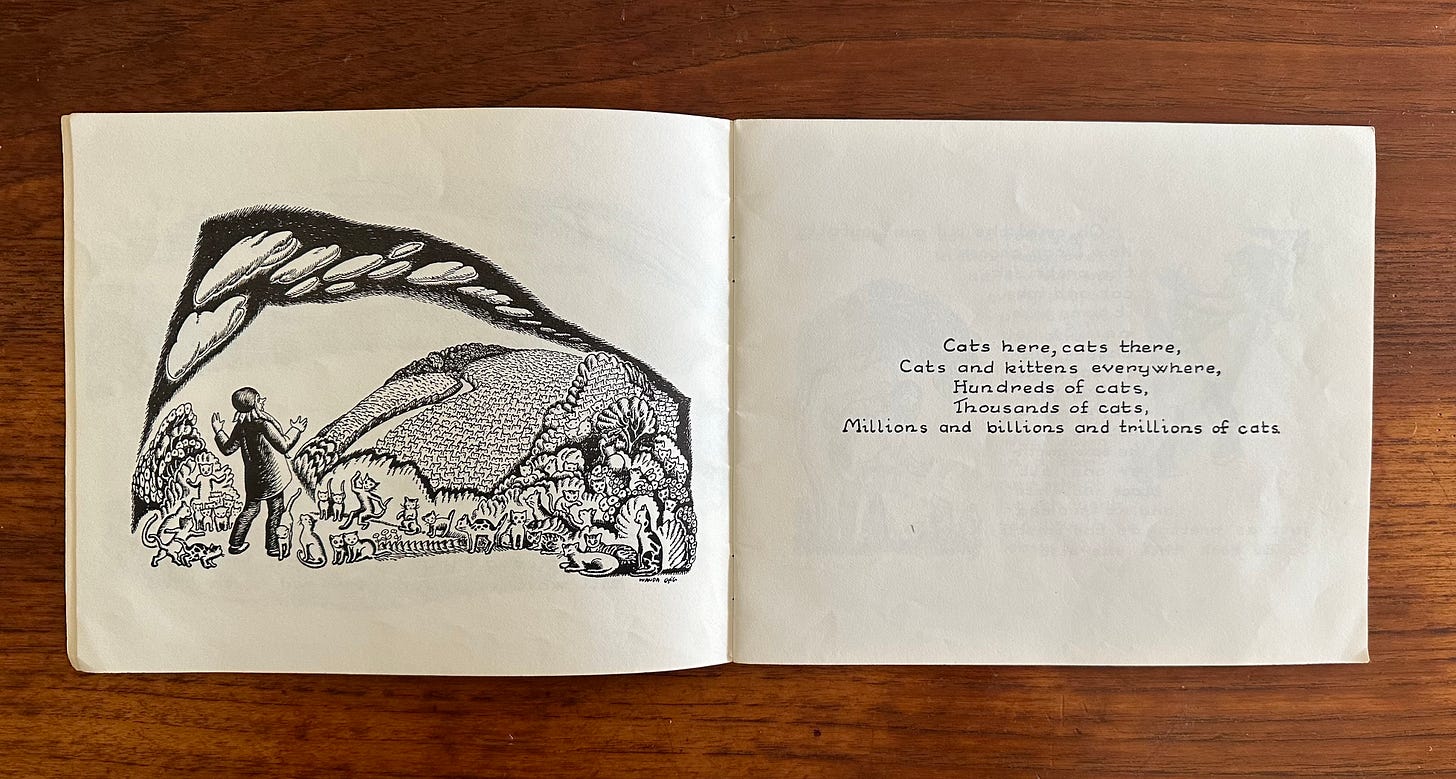

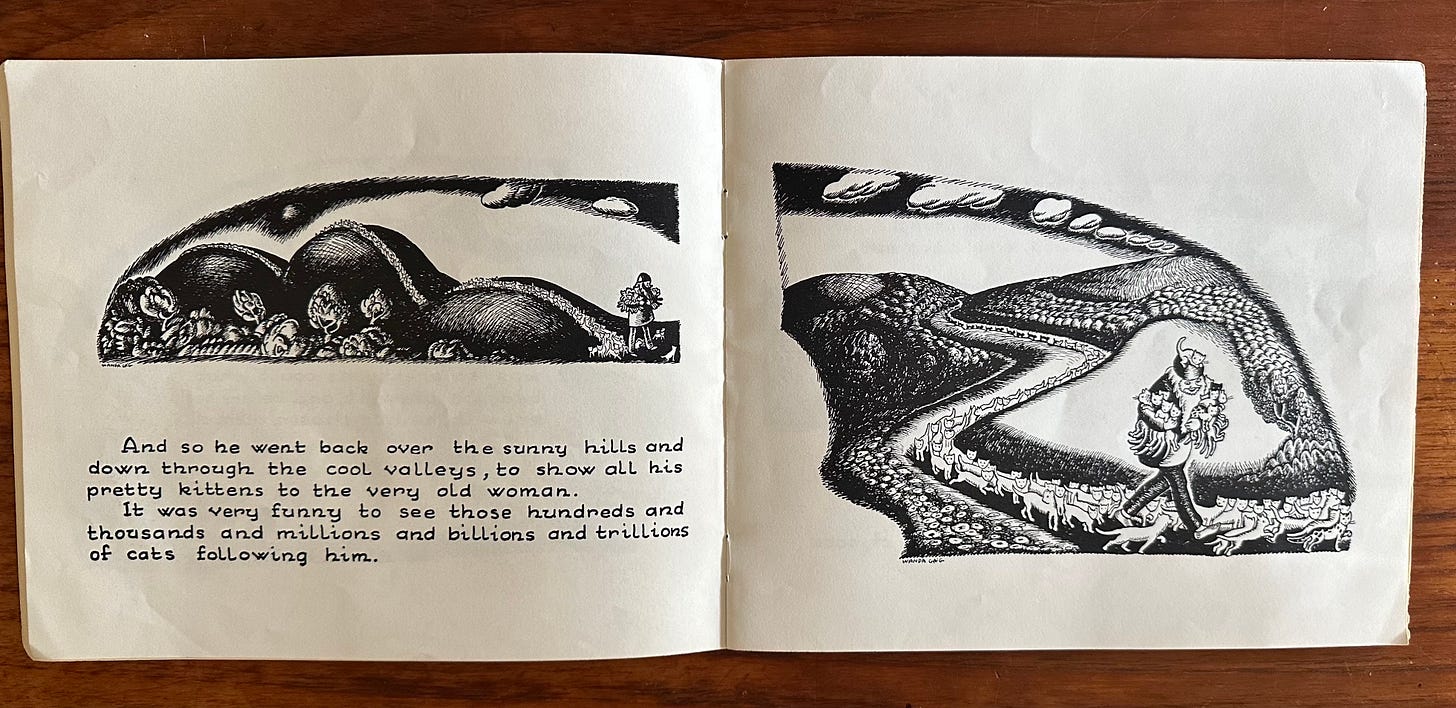

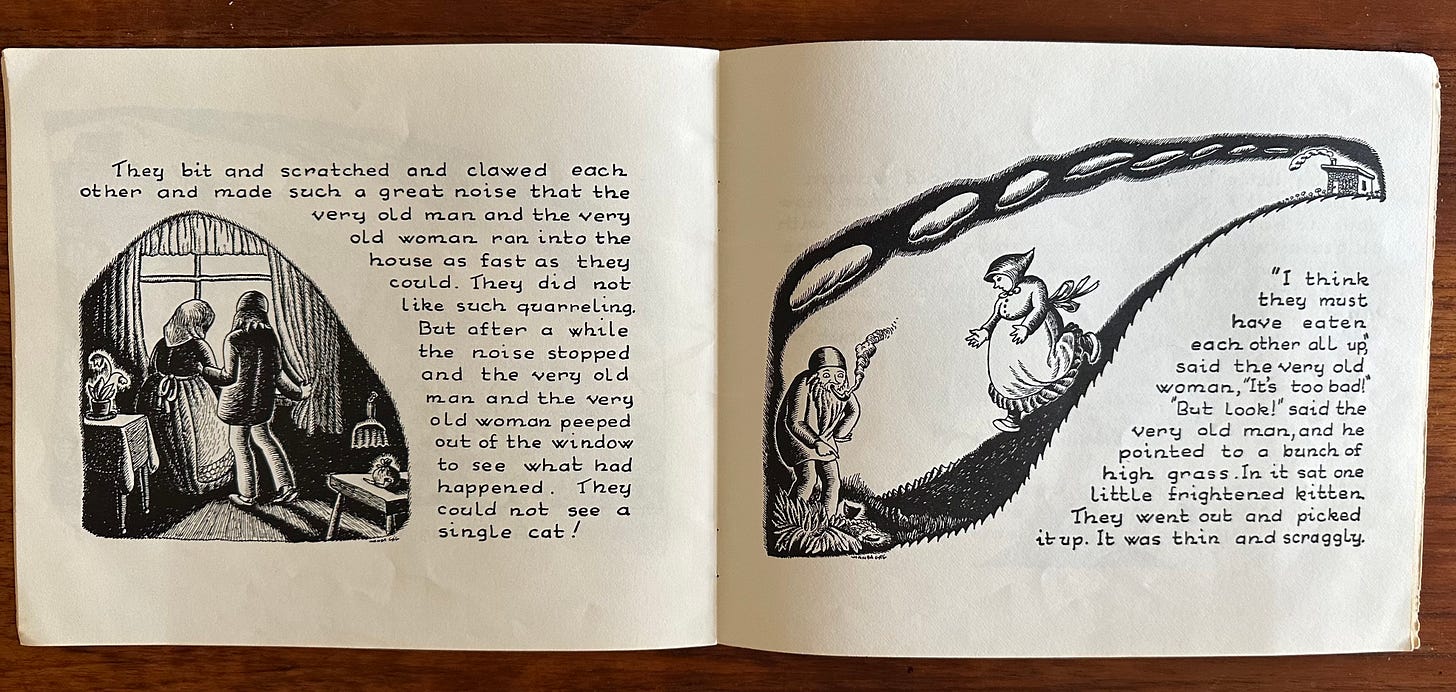

Millions of Cats is Gág’s original folktale story of a lonely old man who sets off to find a cat companion for him and his wife. But instead of one cat, he comes back with “hundreds of cats, thousands of cats, millions and billions and trillions of cats!” Unable to choose just one, he decides to keep them all, that is, until his wise wife reminds him the cats will eat them out of house and home. They decide to keep the prettiest cat but let the cats choose who that is. Chaos ensues! The cats quarrel and, presumably, eat each other up because they all disappear—except for one homely little kitten. The old man and woman take it in, and with a bit of love and care, the kitten turns out to be very pretty indeed.