Be as Open to Influence as Possible

Margaret Wise Brown, Maggie Nelson, Consuelo Kanaga, the moon, and me.

Thanks to fake news, corporate interests, and the rise of social media stars, the word “influencer” has gotten a bad rap. We see most of today’s influencers as inauthentic and dishonest, which is why I cringe when someone refers to me as one. There were times in my career when I felt like the commercialization of my brand was ruining it—and me. It’s a fate that most businesses looking to scale must contend with. Sometimes, I’m a little jealous of people who aren’t bothered by it. Still, I found it unsustainable. It’s not that I’m entirely against commercial endorsements, but they’re difficult to get right, and the more you’re forced to do, the less true influence you have. But for me, the pleasure of the internet is the pleasure of influence—in the amalgamation of shared connections, voices, and ideas. But nowadays, to admit to being influenced seems like a confession of unoriginality, or worse, weak-mindedness, but I don’t believe that. Even those who pride themselves on their unique sensibilities are influenced by things; they just refuse to recognize them. When I’m influenced by something, my first impulse is to share it. It’s no fun to keep it to myself. And now, as someone who writes about art and ideas, recognizing influences both in the works and in myself is critical to unpacking them.

The word “influence” comes from medieval Latin for “influentia,” meaning “to flow into.” This inflow seeps into porous spaces, which is why commercial brands want to blur the line between authentic recommendations and paid advertisements. However, a consequence of that is distrust—we become closed off to other people's ideas. I try to be as open to influence as possible. One of my favorite writers, Zadie Smith, talks about this a lot. In an essay “That Crafty Feeling” from Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays (2009), she writes:

It’s a matter of temperament. Some writers are the kind of solo violinists who need complete silence to tune their instruments. Others want to hear every member of the orchestra—they’ll take a cue from a clarinet, from an oboe, even. I am one of those. My writing desk is covered in open novels. I read lines to swim in a certain sensibility, to strike a particular note, to encourage rigor when I’m too sentimental, to bring verbal ease when I’m syntactically uptight. I think of reading like a balanced diet; if your sentences are baggy, too baroque, cut back on fatty Foster Wallace, say, and pick up Kafka, as roughage. If your aesthetic has become so refined it is stopping you from placing a single black mark on white paper, stop worrying so much about what Nabokov would say; pick up Dostoyevsky, patron saint of substance over style.

She goes on to talk about the English poet John Keats.

A suburban, lower-middle-class boy, a few steps removed from the literary scene, he made his own scene out of the books of his library. He never feared influence—he devoured influences. He wanted to learn from them, even at the risk of their voices swamping his own…The term role model is so odious, but the truth is it’s a very strong writer indeed who gets by without a model kept somewhere in mind. I think of Keats. Keats slogging away, devouring books, plagiarizing, impersonating, adapting, struggling, growing, writing many poems that made him blush and then a few that made him proud, learning everything he could from whomever he could find, dead or alive, who might have something useful to teach him.

This insatiable hunger—for books, for words, for art—feels gluttonous, but it fuels me. Like Smith, my desk is covered with open books, their pages dog-eared and furiously underlined. My internet browser is similarly stuffed full of open tabs, each with a tasty morsel of something I want to keep eating. My excessive need for more is only curbed by an even stronger need to purge. I have to get it out. But I resist, I rest, and I wait for it to metabolize. I constantly have to remind myself that this uncomfortable period of waiting is essential to my creative process. It’s why I write so slowly. Most of my writing happens in my head, sometimes consciously, but more often unconsciously. Everything I’ve ingested is being converted into energy that will fuel my next idea.

Something I find fascinating about the devouring phase is how a seemingly random book, article, or conversation will spark a connection that will unlock an idea. Or how a divergent path can lead me to my desired destination. These happy accidents are subtle; if I’m closed off in any way—too tired, too distracted, too cynical—I will miss them. I often think alone time is all I need to supercharge my ideas. However, being social (something I’m not always good at), moving my body, getting in nature, listening to music, watching films, and trying new things are also essential parts of my writing process. But none of these are as influential as reading. Reading changes everything.

Again, it’s about being open. I read widely; no genre, form, or style is off-limits, and when I find something I love, I go deep. I read every single thing by that person, watch all their videos, and listen to every single one of their interviews. I’m not worried I’ll end up sounding like them or steal their ideas, although I’m sure both of those things have happened. As long as I’m reading other voices at the same time, I’m confident that my balanced reading diet will be converted into something different, something that’s me.

Here’s what’s influencing me lately:

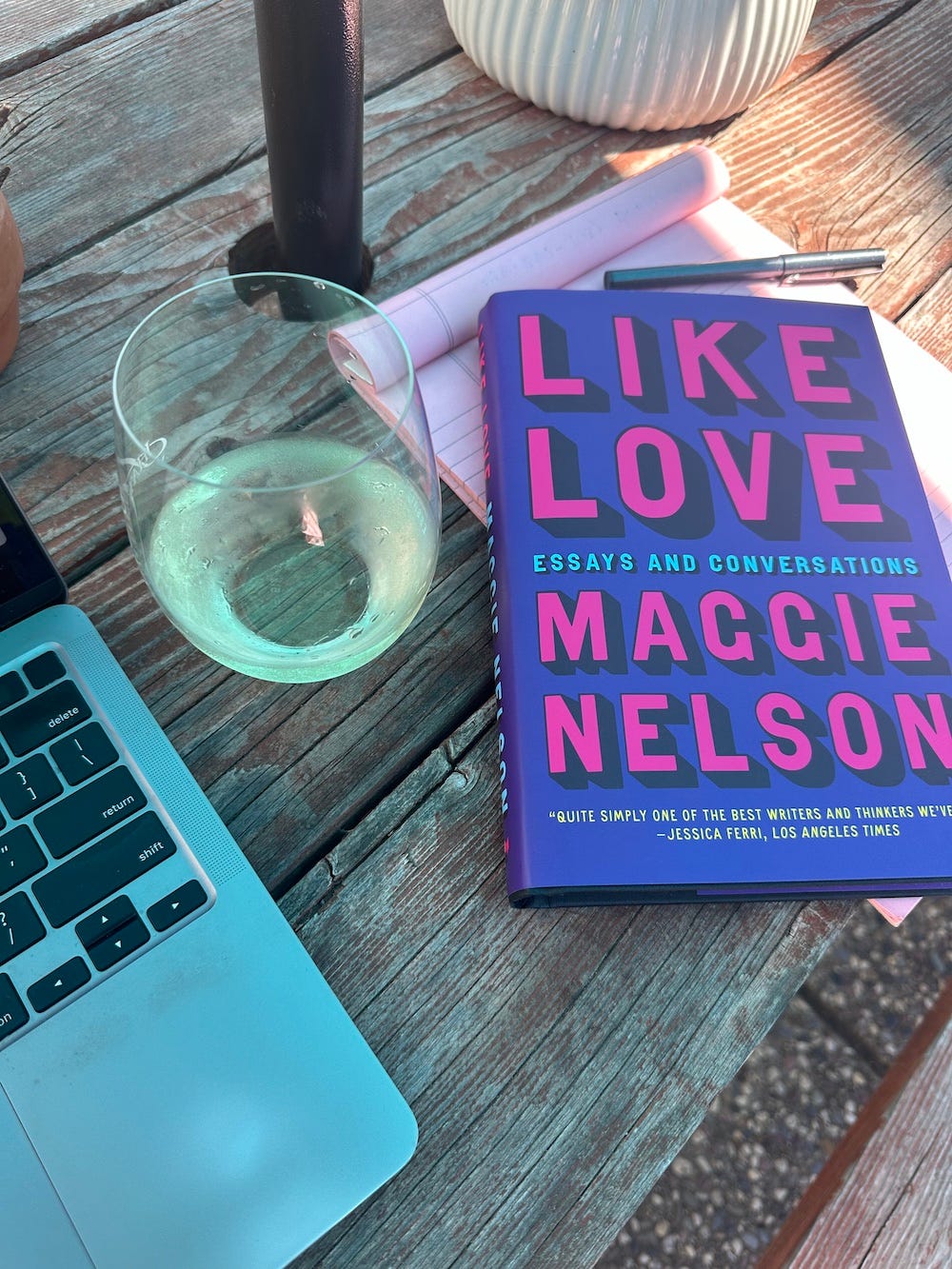

Reading Maggie Nelson’s Bluets (2009) and The Argonauts (2015) is an expansive and enlightening experience—both changed me as a reader. Her books defy classification—spanning (and often mixing) poetry, autobiography, art criticism, and theory. In his 2016 piece for The New Yorker, “Maggie Nelson’s Many Selves,” the writer Hilton Als describes Nelson’s work beautifully, “It’s Nelson’s articulation of her many selves—the poet who writes prose; the memoirist who considers the truth specious; the essayist whose books amount to a kind of fairy tale, in which the protagonist goes from darkness to light, and then falls in love with a singular knight—that makes her readers feel hopeful.”

In the preface of her latest book, Like Love: Essays and Conversations (2024), Nelson mentions Als, quoting an assertion of his that she thinks of often, partly because she is delightfully perplexed by it: "every mouth needs filling: with something wet or dry, like love, or unfamiliar and savory, like love.” She goes on to ask, “What is something ‘like love’ but not love? Would such a thing be a cruel—perhaps the cruelest—of substitutes? Or can something that’s like love, but not love, offer its own form of sustenance? How would you know the difference? How can the attention one pays to art be an act of love, or something like it, if and when the love object (words, sounds, paint, pixels) cannot love you back?”

Of course, as Nelson asserts, we feel love for things and people who don’t love us back all the time, but who’s to say how these things love us anyway? When it comes to art, one of the best ways to express our love is through language, but there’s often the fear that language will ruin the aesthetic experience or feel forced. It’s not easy to talk or write about art, “but sometimes you must explain. And not just because someone asked, or because we live in a culture of explanation, but because one wants to. Needs to. The language rises up, an upchuck. Words aren’t just what’s left; they’re what we have to offer.” 1

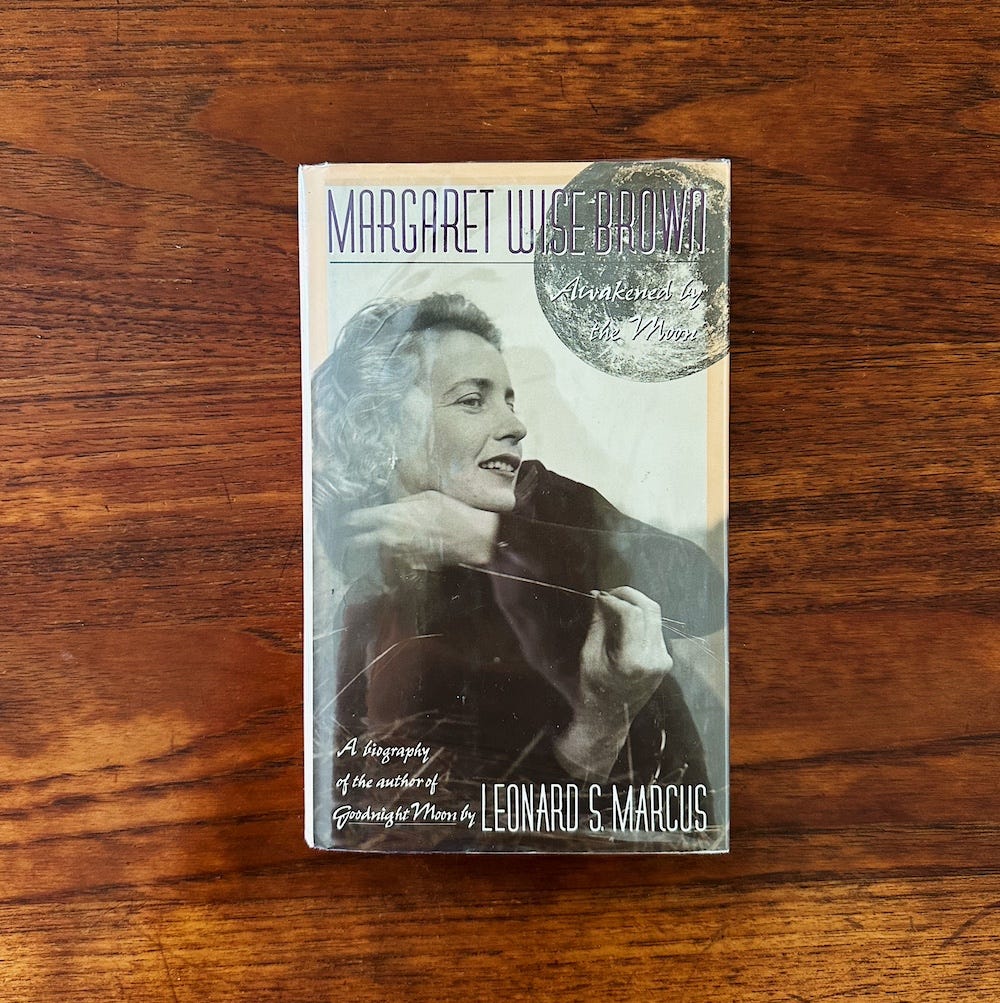

Nelson recently spoke to Frances Richard for the City Arts & Lectures. I’d never heard of Richard, so I looked her up. She’s an interesting writer, but what piqued my interest was her piece about the photographer Consuelo Kanaga’s portraits of Margaret Wise Brown. (Somehow, everything circles me back to MWB!)

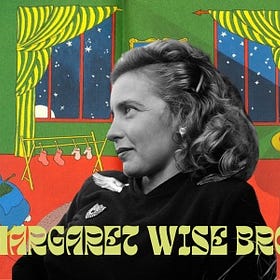

Of the small selection of photographs available of Brown on the internet, Kanaga’s are by far the best. Her dreamy black-and-white photos capture Brown’s alluring, enigmatic spirit. She rarely looks directly at the camera; instead, she looks off into the distance, a delicate trace of a smile on her face. She’s gorgeous, like a 1940s movie star. Her hair is coifed in a soft pompadour, Greer Garson-style, and she’s dressed in a dark elegant dress with two (presumably) gold wings on each shoulder. Despite her glamour, there’s nothing precious-feeling about her. In many of the photos, she’s outside, lying in the middle of a grassy field, hugging her dog, Crispin's Crispian. In one of my favorites, she’s dressed in dark jeans and a men’s tweed blazer, casually leaning against a tall pile of rocks, looking down at the water. She appears to be holding a glass, perhaps a champagne coupe; it’s not clear. I’ve poured over these photos so many times that I’ve created my own story about them. I fill in the blanks with pieces of information I know about Brown or have seen in other photographs. She’s familiar and yet completely mysterious.

In my story, Brown and Kanaga got along swimmingly—laughing, drinking, sharing a smoke, and perhaps a few secrets. There’s no official account of their meeting. Kanaga, as Richard points out, isn't mentioned in either of Brown’s biographies—so as far as we know, my imaginings are as good as true.

Brown was undoubtedly a fascinating force, but as Richard writes, Kanaga was a renegade in her own right. In 1915, she worked as one of the only female photojournalists for the San Francisco Chronicle and became known for her beautiful and sensitively documented photographs of Black American families and migrant workers.

Kanaga also took sensual still lifes of flowers and household objects. Like Brown, she was fascinated by ordinary things.

“I have rather wanted my photographs to be very plain, everyday things. They aren’t dull because everyday things aren’t dull.”2

Even though Brown and Kanaga worked in different mediums, they shared artistic sensibilities. Their art is dreamy, poetic, surreal, and, at the same time, firmly grounded in the “here and now.”3 Brown’s children’s books are, like Kanga’s photographs, portraits of daily life; they uncover the hidden joys and mysteries of the everyday.

“What is there in thee, Moon! That thou should'st move my heart so potently?” — John Keats

Paying subscribers get total access to everything Moonbow publishes. That means:

Complete access to Moonbow’s literary criticism, reviews, and recommendations.

Exclusive access to book guides, video meet-ups, online courses, and merchandise (coming soon!).

The full archive of Moonbow’s articles, dating back to March 2022.

But more importantly, becoming a paid subscriber allows Moonbow to stick around! While it’s fun, it’s definitely not easy to dedicate hours to researching, writing, editing, and marketing this publication. So, if you enjoy Moonbow and want to support it, becoming a paid subscriber is the best way.

Moonbow has many amazing opportunities to grow and become a more robust platform for children’s books. By becoming a paid supporter, you’re helping make those dreams a reality.

You might like…

Margaret Wise Brown and the Art of Paying Attention

“A book can make a child laugh or feel clear-and-happy-headed as he follows a simple rhythm to its logical end. It can jog him with the unexpected and comfort him with the familiar, lift him for a few minutes from his own problems of shoelaces that won’t tie and busy parents and mysterious clock-time, into the world of a bug or a bear or a bee or a boy …

Like Love: Essays and Conversations by Maggie Nelson (2024), preface, page xii

In a Picture: “Margaret Wise’s Boudoir” by Frances Richard, Places Journal (2024)

The “Here and Now” approach, an educational theory developed at the Bank Street Experimental School in New York, argued that children’s books should focus not on fantasy and faraway lands, but on the objects and experiences of everyday life (Sprague Mitchell, 1921).

Taylor, I don’t know how you do it, but I admire it so much — you’re a wonderful writer, thinker, critic, and person. Kudos, once again, on another excellent post.

Thanks for introducing me to Maggie Nelson! Off to spend some more $$ now.