The Little Island

“This is a wonderful wild place."

If you enjoy reading Moonbow, please consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber. You can read more articles about Margaret Wise Brown in the archive.

My kids start summer break this week, which means I also start summer break. Calling it a “break” is ironic, it’s more like a mental marathon where I see how long I can juggle the relentless tasks of being a mom and freelance work before I breakdown. However, I’ve always had a complicated relationship with summer, even before I had kids.

When I was young, summer was fine as long as I was doing things I enjoyed (swimming, going to the movies, listening to music, reading), but often I was at the whim of my parents’ agenda, like being dragged to Sears or some other horribly boring place. Most of the time, I was content without a sibling to play with (my half-sister is 12 years older than me), but on those boring outings, stuck inside a dingy department store, underneath flickering fluorescent lights, it’s all I wanted.

I remember those slow, summer errands, driving around town, sitting in my parents’ car—the leather seat slicked with sweat under my thighs while hot wind blew in from the open windows and through my hair, my dad’s favorite talk radio station babbling incessantly in the background—daydreaming of being back at school, not because I particularly loved school, but at least there I could be with my friends. Summer was lonely.

Now, as an adult, it’s much the same. Even though my family is together more in the summer than in any other season, the long sunny days still give me a faint feeling of loneliness, it’s as if my childhood longings are lifted to the surface—like beads of sweat on the skin—by the hot air. I imagine it’s similar to the way some people feel sad during Christmas even when they’re surrounded by loved ones and holiday cheer. Life is strange like that.

To combat these feelings, I try to lean into boredom and remind myself that some of life’s greatest pleasures happen in slow, concentrated moments; moments that I’m sure I’ll miss when my kids are older and I have more free time. When restless feelings rise up, I think of something the iconic children’s author Margaret Wise Brown wrote, “It is wonderful to just know the importance of lying in the sun.”1

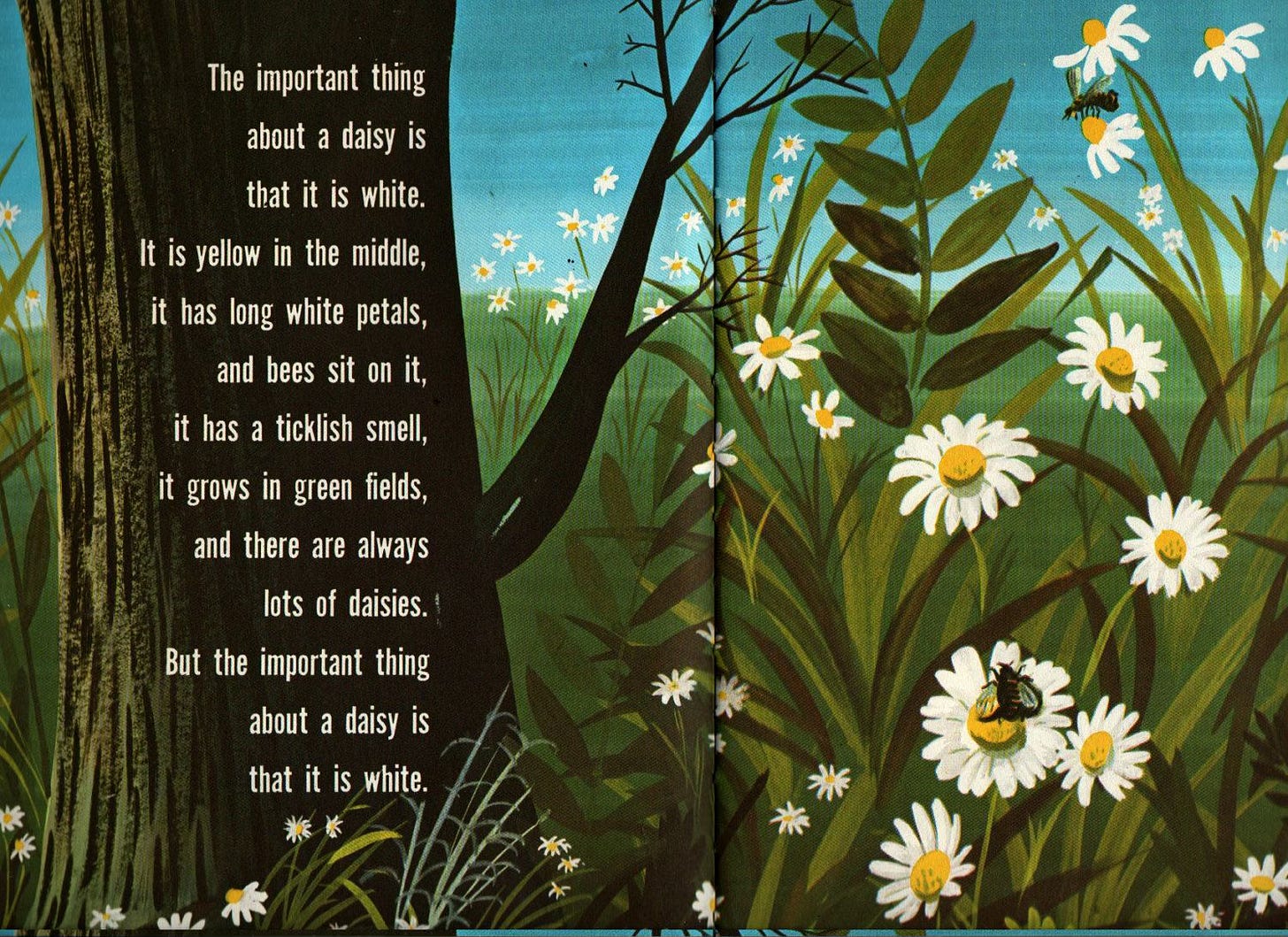

Most—if not all—of Brown’s books remind me of what’s important in life, not obvious things, but things that are often overlooked, especially in our distracted digital age. Brown actually wrote a book about this called The Important Book (1949), illustrated by Leonard Weisgard, where she points out seemingly ordinary things and provokes us to see them in new, peculiar ways—similar to how a child may see them.

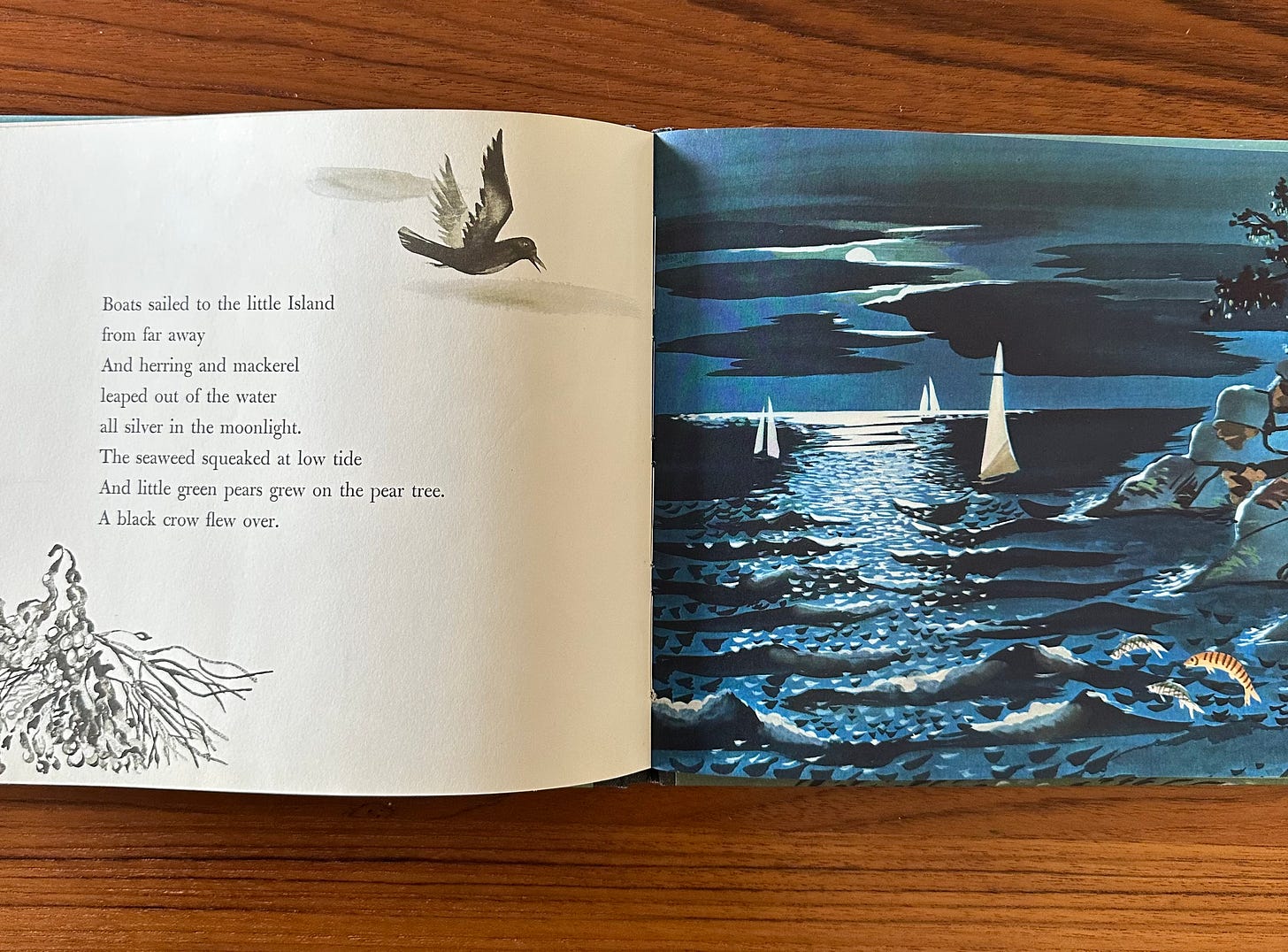

I often read Brown’s 1946 book, The Little Island (also illustrated by Weisgard) in tandem with The Important Book. To me, both stories are about seeing and not seeing. How can we see something we look at every day anew? And how do we believe in something we cannot see? These are questions artists ask, but children are naturally good at doing both these things; they don’t have fixed ideas, their worldview is wild and alive, full of turbulence, change, and—the important thing—possibility.

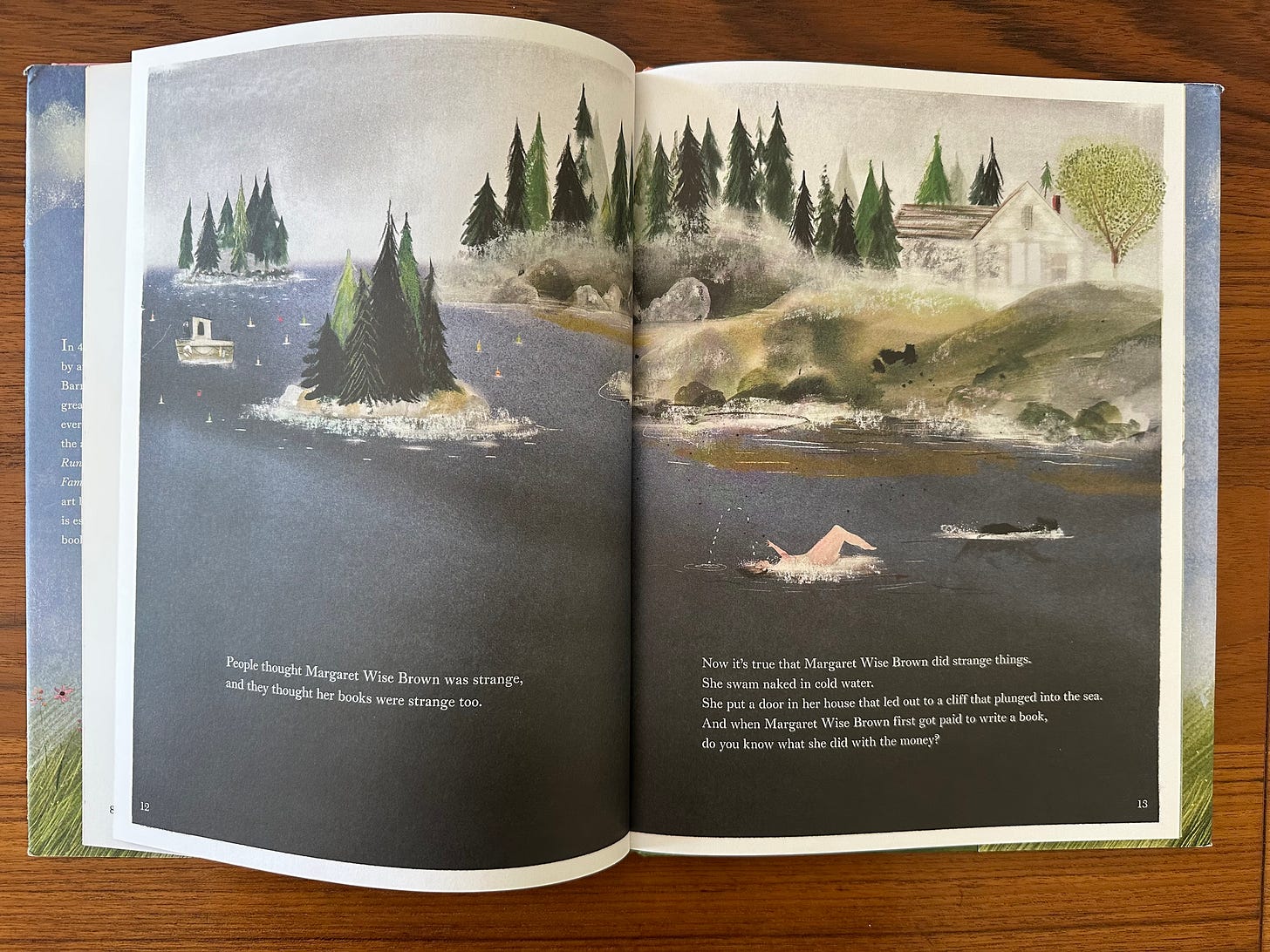

While the book never specifies its location, The Little Island is a real place. In the late 1930s, Brown began spending the summers on the Vinalhaven islands off the coast of Maine as a way to escape hectic city life. “This is a wonderful wild place,” she wrote, “The only way to get here is to come with a lobsterman or fly in a plane. Have been generating here with friends for a month. . . . But most of the ink poisoning impulse has gone away for the moment.” 2

Brown fell in love with Vinalhaven and decided to purchase an abandoned old quarry master’s house she nicknamed the “Only House.” It was delightfully eccentric (at least to her) with no electricity or plumbing and an open-air boudoir. There was even a second-story door that opened straight out into thin air; Brown mischievously called it “The Witch’s Wink.” She kept her food cold in an outside well, butter and milk were tied with ropes and retrieved by a pulley system, and she chilled wine bottles in nearby streams. Like Brown, the Only House was innovative and playfully challenged the status quo. While there, Brown wrote about the little island she could see outside her window. She marveled at its beauty and resilience as it endured the changing temperaments of the seasons; something, I think, she related to.

The Little Island is vivid and poetic; it includes some of Brown’s most exquisite nature writing.

There was a little Island in the ocean.

Around it the winds blew

And the birds flew

And the tides rose and fell on the shore.

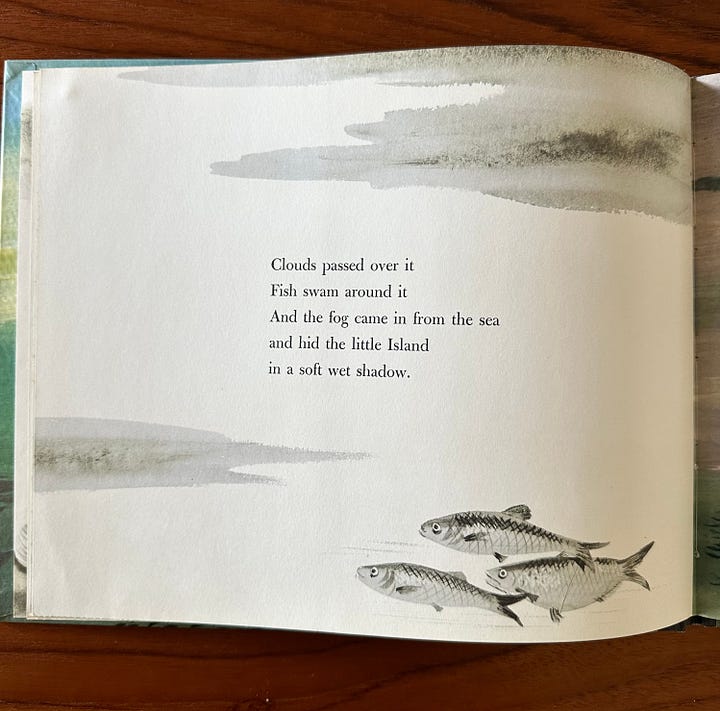

Clouds passed over it

Fish swam around it

And the fog came in from the sea

and hid the little Island

in a soft wet shadow.

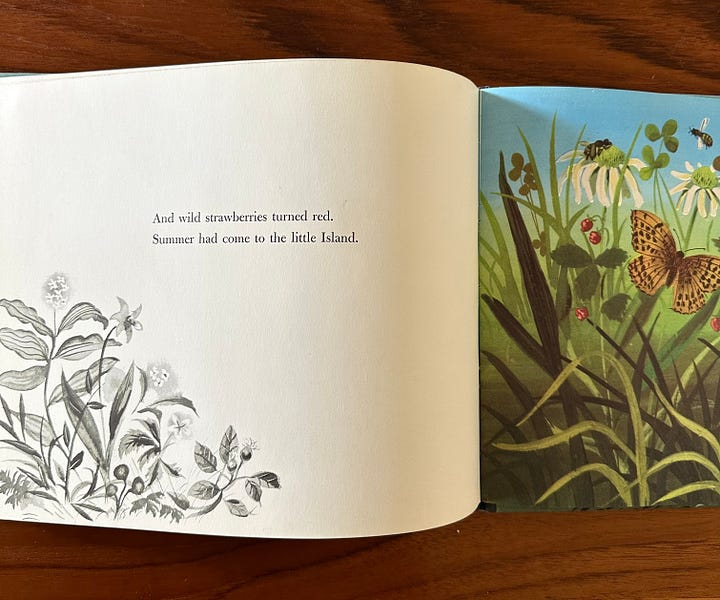

The text and images provide children with sensuous depictions of nature on the small island, and show how the shifting seasons affect everything that lives on and around it: wildflowers, lobsters, gulls, fireflies, strawberries, seals, even seaweed—nothing goes unnoticed under Brown and Weisgard’s watch. It’s all lovely and lyrical, until suddenly, Brown introduces a curious kitten who engages in a philosophical conversation with the little island.

“What a little land,” said the kitten.

“This little Island is as little as Big is Big.”

“So are you,” said the Island.

“Maybe I am a little Island too,” said the kitten—

“a little fur Island in the air.”

And he left the ground and jumped in the air.

“That is just what you are,”

said the little Island.

“But I am a part of this big world,”

said the little kitten.

“My feet are on it.”

“So am I,” said the little Island.

“No, you’re not,” said the kitten.

“Water is all around you

and cuts you off from the land.”

“Ask any fish,” said the Island.

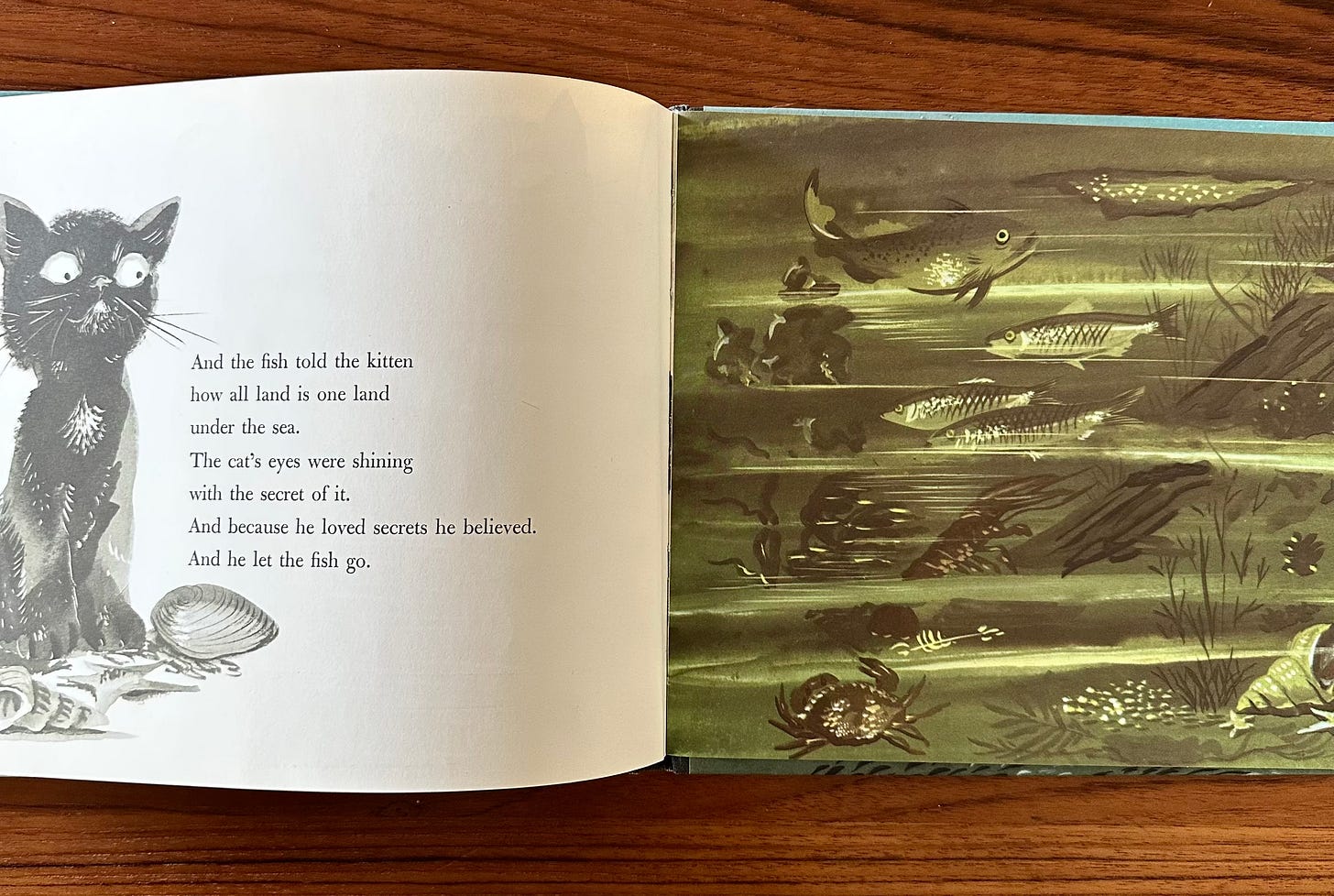

When the kitten catches a fish and demands to know how the little island could possibly be connected to the larger land, the fish tells him to come “down into the dark secret places of the sea and I will show you.” But the kitten can’t swim.

“Then you must take it on faith what I tell you,” said the fish.

“What’s that?” said the cat—“Faith.”

“To believe what I tell you

about what you don’t know,” said the fish.

Then comes one of my favorite spreads in the book:

And the fish told the kitten

how all the land is one land

under the sea.

The cat’s eyes were shining

with the secret of it.

And because he loved secrets he believed.

And he let the fish go.

Satisfied with his belief in the secret, the little kitten “got on his boat and sailed away into the setting sun.”

Not everyone is a fan of this divergence in the middle of the story. Children’s literature historian Leonard S. Marcus writes in his biography of Brown3 that in some respects the story is “poised and exquisite,” but it “falters in its plot line” with the middle-section’s “portentous dialogue.” Concluding that “Margaret’s conscious striving for a big statement had not worked; grandiose gestures simply did not become her as a writer.” 4

I agree that the middle-section’s message is slightly more heavy-handed than in most of Brown’s stories—and normally the whiff of moral purpose in a picture book is a turn off—but her poetry doesn’t preach, it suggests. Brown gives us a somewhat Nietzschean concept of nature and the self, suggesting that to be a human is to exist both as part of a larger world and as a unique individual within that world. Without the kitten’s conversations with the island and the fish, the parallel rhythms of change and growth between nature and humans would not be as apparent, and even with it the meaning is not explicit, but that’s the point: the mystery of it. Still, I understand why some readers would prefer it was left out—but I think those readers are adults. It may go over some kids’ heads, but there will also be kids who get it, or—more interestingly—disagree with it. Either way, it’s an opportunity for adults and children to have a philosophical discussion. Why does the kitten love secrets he believes? Some adults interpret this as a spiritual allegory, but I read it as a fundamental human truth: in order to survive, we must have faith in things we cannot see—love, hope, trust—even when the world around us changes, even when we ourselves change.

“And it was good to be a little island.

A part of the world

and a world of its own

all surrounded by the bright blue sea.

Despite mixed reviews, The Little Island is one of Brown’s most famous books. In 1947, Weisgard received the Caldecott Honor for his rich and dynamic illustrations. In his acceptance speech, he beautifully weaves the story of The Little Island with his own, and expresses a deep respect for children’s taste and intelligence.

“Fortunately children looking at books, or children drawing, singing, watching or just listening, seem to catch instinctively those details which are most important to them. They focus without being hampered by superficialities. And with this faculty of perception, children are closer to the primitive and nearer to significant detail. Children are never as disturbed as grown-ups by contemporary arts, a streamlined plane, or a gallery of modern painting. They see an image with real meaning and vitality and sometimes with incongruous humor giving it a sharper reality.

…These first experiences which we so intensely felt had sometimes real meaning. And when the meaning was too deep to explain, this would then become our magic. As we grow older and taller we do seem to forget this magic and some of our original truths.

…I can’t tell you in the language of the fish from the Little Island, how all the land is one land under the sea. Perhaps I can try to explain how pictures for The Little Island and Golden MacDonald’s text grew right up out of the water.”5

(The whole speech is remarkable; you should read it.)

The “Golden MacDonald” Weisgard refers to is actually Margaret Wise Brown. Because she was so prolific, she went by a few different pen names. The anonymity allowed her freedom to experiment with different styles. But Golden MacDonald wasn’t just a pseudonym; he was a real person—a Vinalhaven handyman and fisherman who was friendly with Brown. He “regularly cruised past the Only House, knowing that Brown often sought rides into the village—and that she had a morning habit of skinny-dipping.”6 And when Brown and her fiancé Jim Rockefeller got caught in a squall while sailing, MacDonald came to their rescue and dragged them aboard while joking “Gawd, Maagrit, you look better wet than dry!”7

Now when I read The Little Island, I think of that lazy summer in 1945, Brown and Weisgard together in the Only House, watching out the window as the morning sun draped the tiny tree-filled island in a blanket of warm golden light before the passing clouds swiftly shifted its hue.8 Those long summer days in Maine were fertile for Brown’s creativity; she wrote some of her best work on the island. It allowed her a, as she once wrote, “Cat Life—which means doing nothing and just watching.”9 Maybe this summer, instead of worrying about juggling everything, I should relish the slow and boring moments. Maybe the secret to cultivating a creative life is knowing the importance of lying in the sun.

Read more about Margaret Wise Brown:

Ver Ploeg, Kate. “How a Maine Fisherman Became Margaret Wise Brown’s Alter Ego: Golden MacDonald was the celebrated “author” of The Little Island and other classics.” Down East, August 2021 issue.

Ver Ploeg, Kate. “How a Maine Fisherman Became Margaret Wise Brown’s Alter Ego: Golden MacDonald was the celebrated “author” of The Little Island and other classics.” Down East, August 2021 issue.

Marcus, S. Leonard. “Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon.” William Morrow, An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishing. 1999.

Marcus, S. Leonard. “Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon.” William Morrow, An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishing. 1999. Page 191.

Caldecott Acceptance Speech – July 2, 1947. www.leonardweisgard.com

Ver Ploeg, Kate. “How a Maine Fisherman Became Margaret Wise Brown’s Alter Ego: Golden MacDonald was the celebrated “author” of The Little Island and other classics.” Down East, August 2021 issue.

Ver Ploeg, Kate. “How a Maine Fisherman Became Margaret Wise Brown’s Alter Ego: Golden MacDonald was the celebrated “author” of The Little Island and other classics.” Down East, August 2021 issue.

A memory of Weisgard’s that he wrote about in remembrance of Brown. Referenced by Anna Holmes in “A Picture-Book Guide to Maine: Children’s stories set on the coast suggest a wilder way of life.” The New Yorker. September 8, 2024.

Holmes, Anna. “A Picture-Book Guide to Maine: Children’s stories set on the coast suggest a wilder way of life.” The New Yorker. September 8, 2024.

I loved this! Definitely will be looking for a copy to read.

We came across The Little Island in a bookstore a couple of years ago and it’s consistently one of my daughter’s (3) favorite books. She loves the cat part, as do I! I love the change. Thank you for this, this was lovely to read.