Maurice Sendak: The Artist Who Loved Words

Notes on writing, sentences, words, rhythm, and connections

1)

The most brilliant last line in literature was written by a children’s author.

“The wild things roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws but Max stepped into his private boat and waved good-bye and sailed back over a year and in and out of weeks and through a day and into the night of his very own room where he found his supper waiting for him—and it was still hot.”

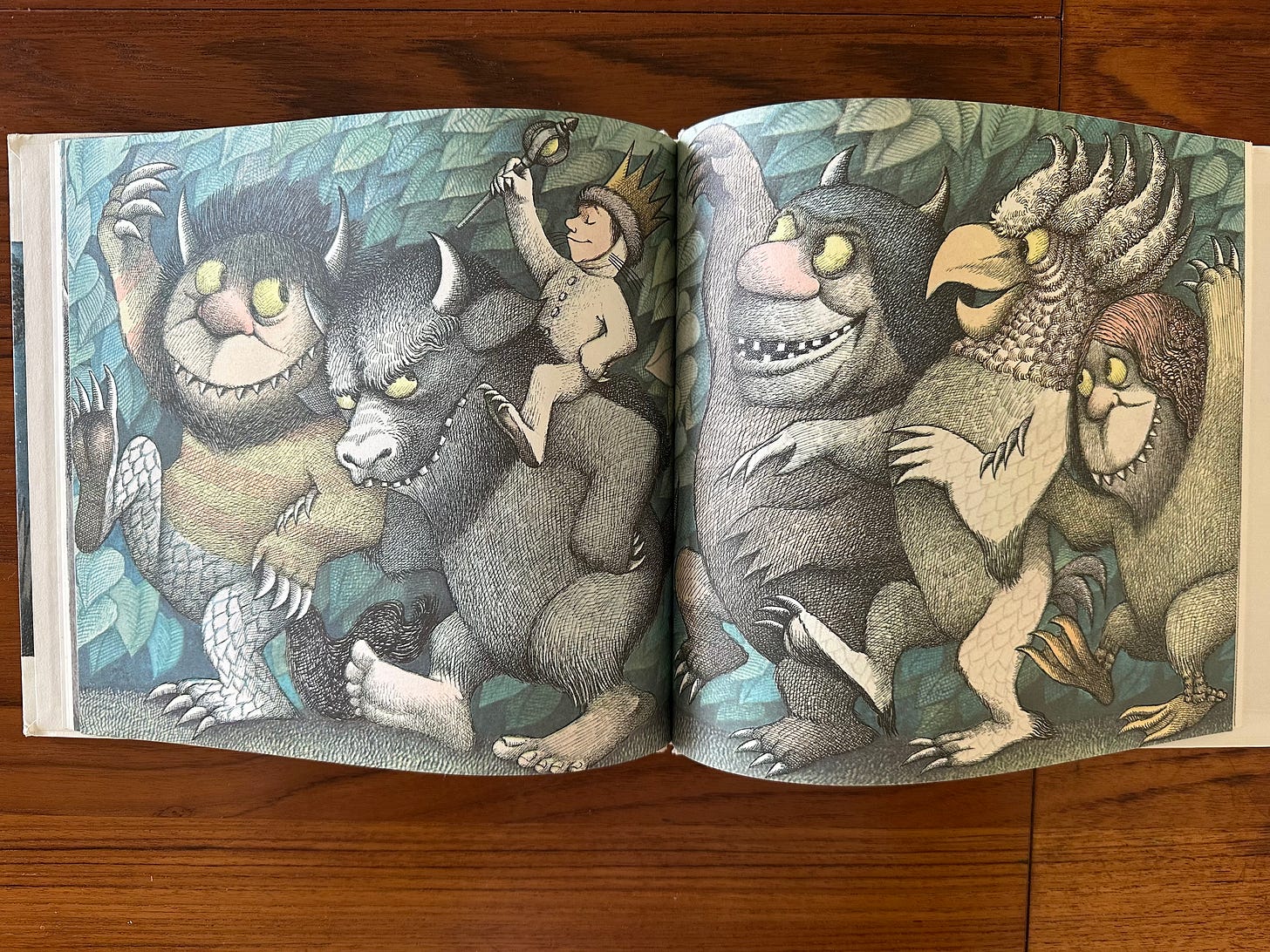

Most of you will recognize this unforgettable last line from the famous picture book Where the Wild Things Are (1963) by Maurice Sendak.

It’s one heck of a sentence even without Sendak’s fantastic illustrations and ingenious layout (although it’s much more effective because of them). Reading it alone—outside of the perimeters of the picture book form—it seems almost impossible it exists. It’s long, a run-on, and lacks commas, but it’s beautifully poetic, and the way Sendak breaks it up across four page turns enhances its rhythm and emotional impact.

In the unexpected final page turn of the book, Sendak leaves us with five words:

“and it was still hot.”

They sit there alone on the page, engulfed in white space with no illustrations, artistically designed to engage readers on multiple levels. Sendak could have easily ended with, “where he found his supper waiting for him,” and he could have stopped on the final illustration of Max safe, back in his room, or worse, he could have drawn Max with his mom cuddling together, or even worse, apologizing to her, turning it into an entirely different kind of story, but he doesn’t. In those five final words, he leaves space for readers to transform the language into meaning.

2)

Deservedly, much has been written about that last sentence. But what about the first sentence? Its sense of immediacy? Its exacting form? The book jumps right in, with no preamble, no description of previous events, no superfluous dialogue or indulgences—instead, it delves directly into a tense scene. We have to rush to keep up, suddenly filling in the events of the night.

“The night Max wore his wolf suit and made mischief of one kind and another his mother called him “WILD THING!” and Max said “I’LL EAT YOU UP!” so he went to bed without eating anything.”

This first sentence is WILD! It is broken up across three page turns (a technique Sendak will repeat in In the Night Kitchen and Outside Over There), and similar to the last sentence, there is a shocking lack of commas, but its unique structure gives it an exciting sense of urgency. Another startling detail is that this is the only time Max’s mother is mentioned in the entire book. By calling Max a “WILD THING!” and provoking him to yell back “I’LL EAT YOU UP!”, she incites the incident that sets the story in motion. She is omnipresent throughout Max’s fantastical adventure—never mentioned but felt—and when he returns to find his hot supper waiting for him in his room, we assume his mother has left it for him—she is the grounding force of reality that bookends the story.

Sendak radically refined the picture book narrative, where text and images share the task of telling a story. Sometimes the text is left out, sometimes the images are left out, but everything is designed to be read. This subtle but complex relationship requires readers to process and integrate two distinct kinds of information, and rewards those who pay close attention (something kids are excellent at). In Where the Wild Things Are, no detail is extraneous: the lack of commas, the capitalization, the sentence structure, the rhythm across page turns, the white space surrounding the images, the wordless spreads, the moon’s phases—all of it influences the emotional experience.

Contrary to popular belief, writing less words does not mean less work. There are only 338 words in Where the Wild Things Are. Every word was thoughtfully considered. It took Sendak ages to decide on the word “rumpus,” in the sentence, “Let the wild rumpus start!”1 He wanted the perfect word for the great peak in the story. In order to find it, he would read a word out loud and listen, then read another word out loud and listen, until he heard exactly what he liked best. Of that famous line, Sendak said, “I’ll never forget it as long as I live,”2 and thanks to him, neither will we.

3)

First sentences in fiction are secret doors. Some open slowly, others swing wide open. The first sentence in Where the Wild Things Are is a swing-wide-open-and-push-you-directly-into-the-heart-of-it sentence.

You know who else wrote those kinds of sentences? Katherine Mansfield.

Here are are some of my favorite Mansfield first sentences:

“And after all the weather was ideal.” (The Garden Party)

"The week after was one of the busiest weeks of their lives." (The Daughters of the Late Colonel)

“And then, after six years, she saw him again.” (A Dill Pickle)

“In the afternoon the chairs came, a whole big cart full of little gold ones with their legs in the air.” (Sun and Moon)

4)

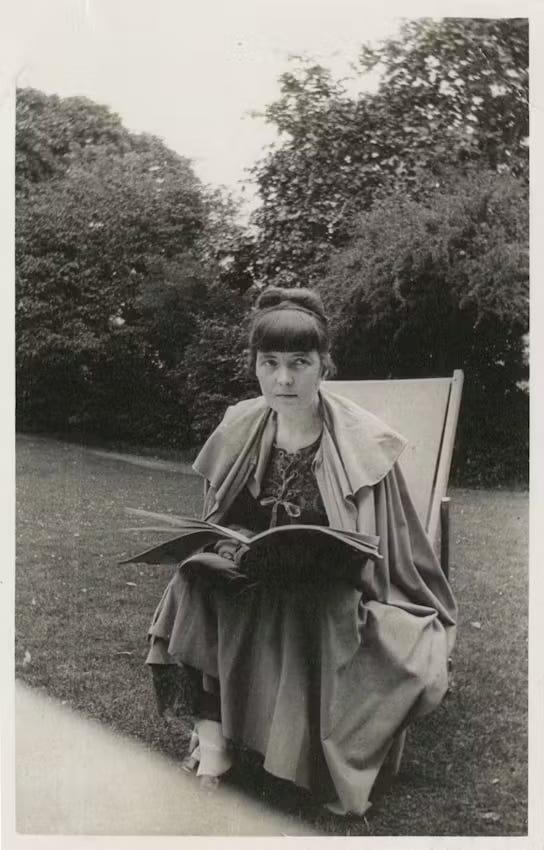

Katherine Mansfield was a modernist writer of short fiction (and poetry, literary reviews, translations, and aphorisms). She was a contemporary and sometimes-friend of D.H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf. Woolf famously wrote in her diary, "I was jealous of her writing—the only writing I have ever been jealous of." Tragically, Mansfield died at the young age of 34 from tuberculosis. After her death, Woolf wrote, “When I began to write, it seemed to me there was no point in writing. Katherine won’t read it.”

Mansfield’s writing is a flash of delight. A phrase that, until a few years ago, I naively thought was my own. I coined the tagline “flashes of delight” to express the essence of my brand Glitter Guide. The name Glitter Guide, while catchy, did not accurately portray my intentions. I wanted words to express that flash or shock you feel when you encounter something astonishing that startles you and snaps you to attention, igniting a sudden and overwhelming alertness to the world. I found out later that Woolf described this phenomenon as “moments of being,”3 and that James Joyce called them “epiphanies,” and “flashes of insight.” This dazzling coincidence is probably why I’m drawn to modernist fiction, but really to any story that makes me notice things beyond my everyday perception.

Sadly, Mansfield never received the same level of recognition as her modernist contemporaries. Some speculate it’s because she died young and was a female queer outsider. But it’s also because she wrote short stories—a form that, even today, is deemed insubstantial compared to the novel.

Sendak was also an outsider, and like Mansfield, he chose to express himself through an undervalued art form: the children’s picture book—which means he will always be excluded from the cannon of “high” literature. (Unless we change that!)

The author Isabel Allende wrote of the short story:

“I think that in a short story the most important thing is to get the tone right in the first six lines. The tone determines the characters. In long fiction, its plot, its character…a lot of stuff goes in there. But in short stories, it’s tone, language, suggestions…People think if they can write a short story then eventually they will be able to write a novel. It’s actually the other way around. If you are able to write a novel, someday with a lot of work and good luck you may be able to write a good short story.”

There are only 10 sentences in Where the Wild Things Are, which means the tone has to be right from the very first sentence. Writing a picture book requires skillful use of condensation, implication, and omission. Perhaps we should extend Allende’s statement: If you are able to write a novel, and you are able to write a short story, someday with a lot of work and good luck, you may be able to write a good picture book.

“The mind I love must have wild places, a tangled orchard where dark damsons drop in the heavy grass, an overgrown little wood, the chance of a snake or two, a pool that nobody's fathomed the depth of, and paths threaded with flowers planted by the mind.” — Katherine Mansfield

5)

The picture book is a sensuous object children can see, hear, smell, and feel—the pages are essential to the form. And the page turn is like a poetic device: it can break a line, change perspectives, shift the tone, create a pause, and build suspense. Think of authors and illustrators like composers. How they “conduct” form, design, sounds, phrases, and words, influences the tempo, creating an impulsive, enlivening force, which Sendak describes as “the essence of a picture book.”

In his 1964 essay, “The Shape of Music,” Sendak uses the word quicken to describe this effect. He writes:

“Vivify, quicken, and vitalize — of these three synonyms, quicken, I think, best suggests the genuine spirit of animation, the breathing to life, the surging swing into action, that I consider an essential quality in pictures for children’s books…The word quicken has other, more subjective associations for me. It suggests something musical, something rhythmic and impulsive. It suggests a beat — a heart beat, a musical beat, the beginning of a dance. This association proclaims music as one source from which my own pictures take life. To conceive musically for me means to quicken the life of the illustrated book.”

Similarly, in a 2002 PBS News interview, Sendak said, “Words, pictures, words, pictures—and it has a tempo—almost a metronome at the beginning. You’ve got to catch them with your metronome right from the start so they syncopate with the book.”

6)

The dictionary defines quicken as “To give or restore vigor or activity; to stir up, rouse, or stimulate: to quicken the imagination.”

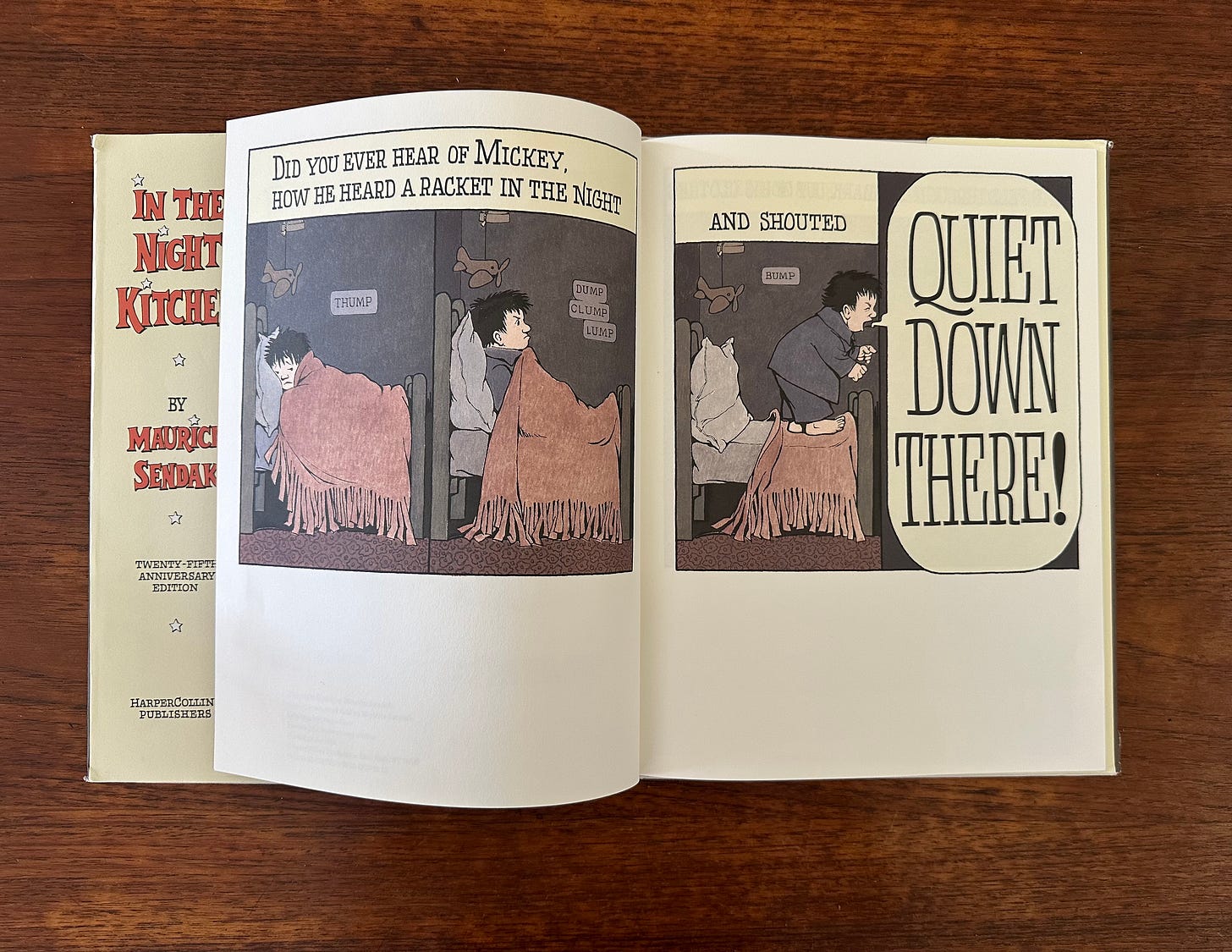

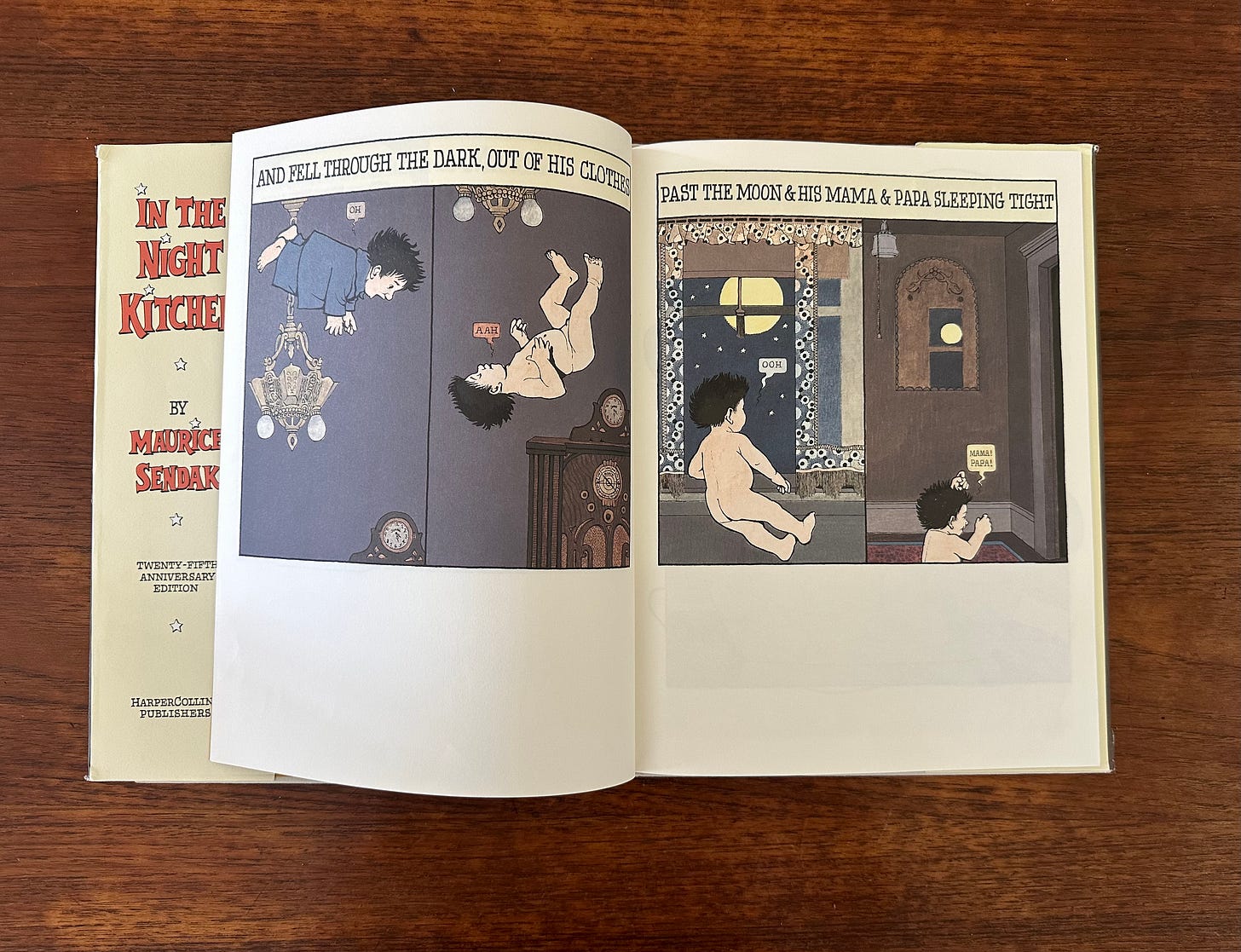

None of Sendak’s books quicken the imagination quite like In the Night Kitchen (1970). It is pure sensation, a strange, cosmic, cake-battered dream, more wild than Wild Things—and more joyous.

Like in Where the Wild Things Are, Sendak swiftly sets the tone, stretching one remarkable sentence across three page turns.

“Did you ever hear of Mickey, how he heard a racket in the night and shouted ‘QUIET DOWN THERE!’, and fell through the dark, out of his clothes, past the moon & his mama & papa sleeping tight into the light of the night kitchen?”

And let’s not forget the sound effects:

THUMP—DUMP, CLUMP, LUMP—BUMP/Oh-AAH-OOH-MAMA! PAPA!

What a scrumptious first sentence (and my personal favorite). Its length, alliteration, rhyming, and lack of punctuation give it a steady on-the-beat rhythm, but its unexpected structure and insertion of a shouting ALL CAPS! moment, breaks up the melody. And the sound effects—should you choose to read them—have a lively, bouncy feel, which is probably why the sound of this story is often compared to ragtime jazz.

In the Night Kitchen is, by far, my favorite Sendak book to read out loud—I almost sing it, and my kids love to “sing” along with me. The sonic texture is intoxicating, like a psychedelic, dream-pop nursery rhyme. We love to chant the rhythmic refrain, “Milk in the batter! Milk in the batter! We bake cake! And nothing’s the matter!” in slightly maniacal tone. It’s great fun!

The syncopated rhythm, chanting, and alliteration, create a yummy mouth feel. The experience of reading In the Night Kitchen reminds me of the linguistic beauty of the first few sentences of Nabokov’s Lolita:

“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.”

moon-mama-papa-tight-light-night

Sendak and Nabokov were sensual writers, they knew how to engage our senses with the sounds of their words, carefully choreographing lips, palate, tongue, giving rise to a pleasurable bodily effect stimulated by the movement of our mouths and an auditory-evoked arousal.

7)

Mansfield cared about the sound of her words, too.

Before becoming a writer, she was a talented musician and considered becoming a professional cellist. Her musical sensibility informed much of her writing. In her journal, she wrote of her short story “Miss Brill”:

“I mean down to the details ... In ‘Miss Brill’ I chose not only the length of every sentence, but even the sound of every sentence – I chose the rise and fall of every paragraph to fit her – and to fit her on that day at that very moment. After I’d written it I read it aloud – numbers of times – just as one would play over a musical composition, trying to get it nearer and nearer to the expression of Miss Brill – until it fitted her. Don’t think I’m vain about the little sketch. It’s only the method I want to explain ... If a thing has really come off it seems to me there mustn’t be one single word out of place or one word that could be taken out. That’s how I AIM at writing. It will take some time to get anywhere near there.”

8)

“…there mustn’t be one single word out of place or one word that could be taken out." If there’s one big takeaway from studying Sendak’s writing, that would be it.

The best writers (especially the best picture book writers) are always the most direct, they get right at the heart of the situation. The words should be arranged in a very simple, poetic order. Let the embellishments be in the illustrations. This doesn’t mean the words should fall flat or be simple-minded, they need complexity and dimension. The trick is how you allow for that.

How do you let so little do so much?

9)

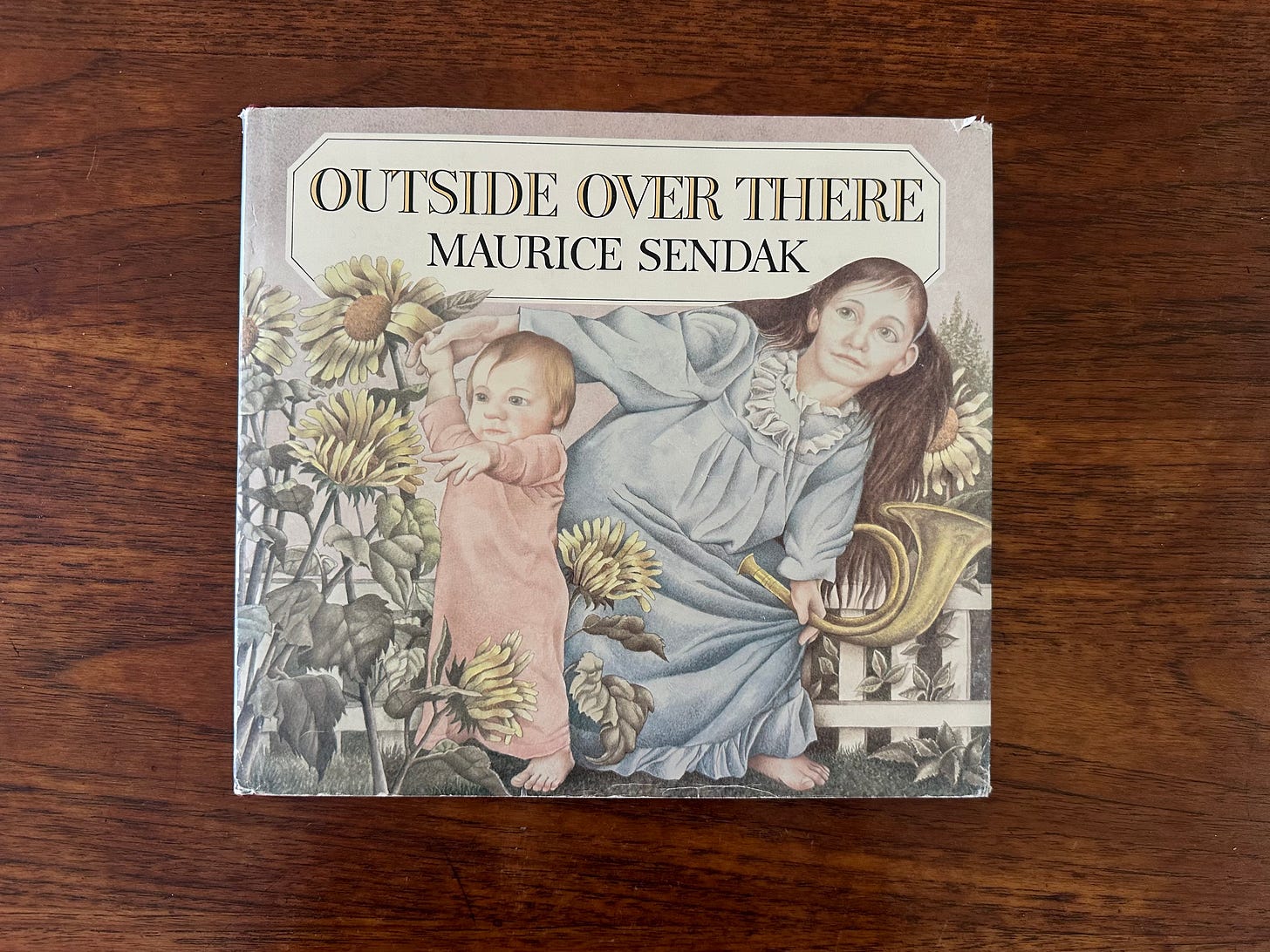

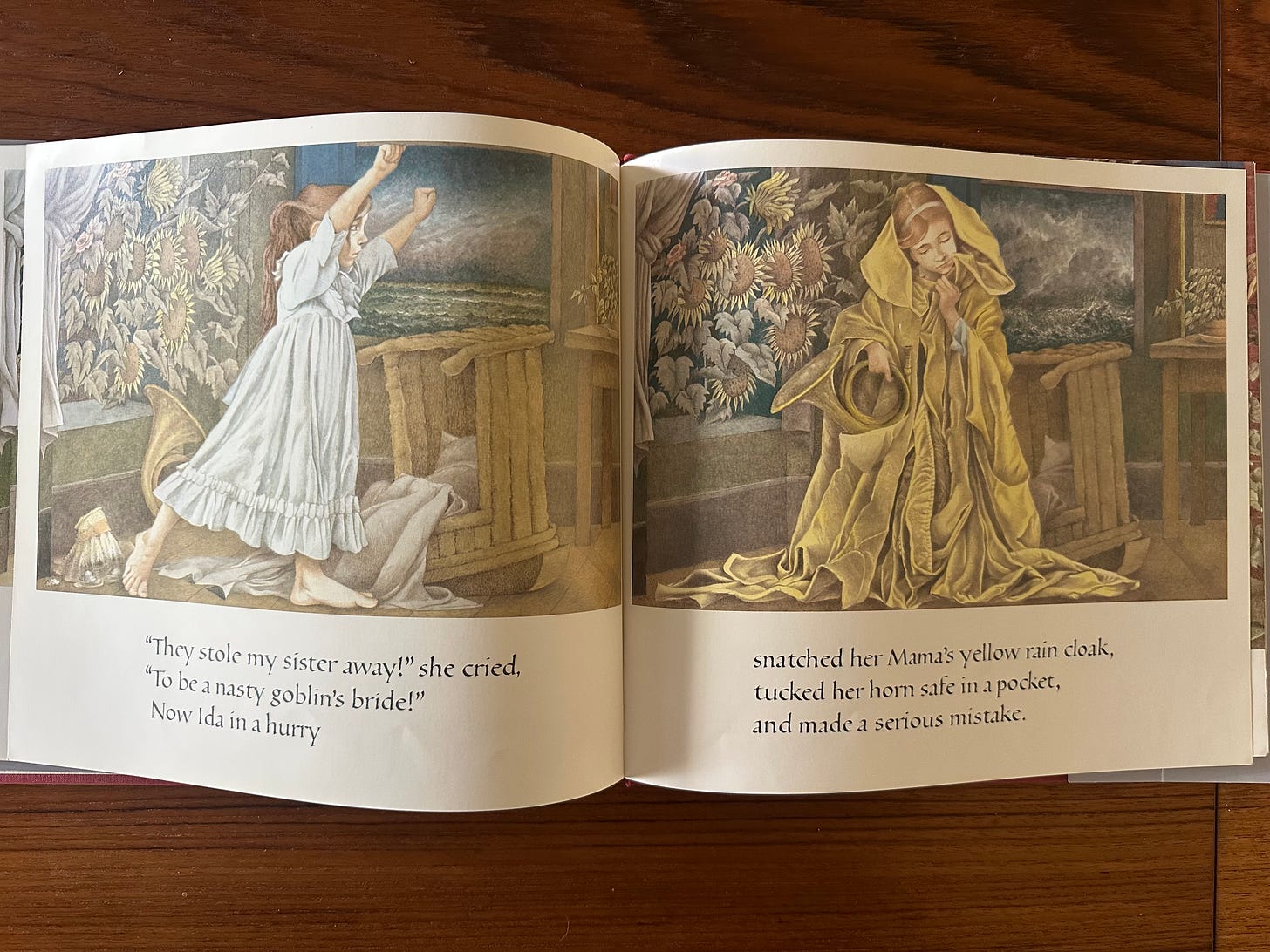

Of all Sendak’s books, Outside Over There (1981), is his most profound; it penetrates the deepest. The visual and textual language are interwoven so suggestively. The pages are brimming with secrets, everything pulsates with meaning.

As a child, I remember the feeling of being lured into this strange book. I wasn’t sure I wanted to read it, or if I was supposed to be reading it, but I couldn’t help myself, and it continues to mesmerize and mystify me.

The sound of Outside Over There is different than the other two in the trilogy. It subverts your expectations by breaking rhyming patterns in unexpected places with delayed gratification, making use of the unique form of a picture book.

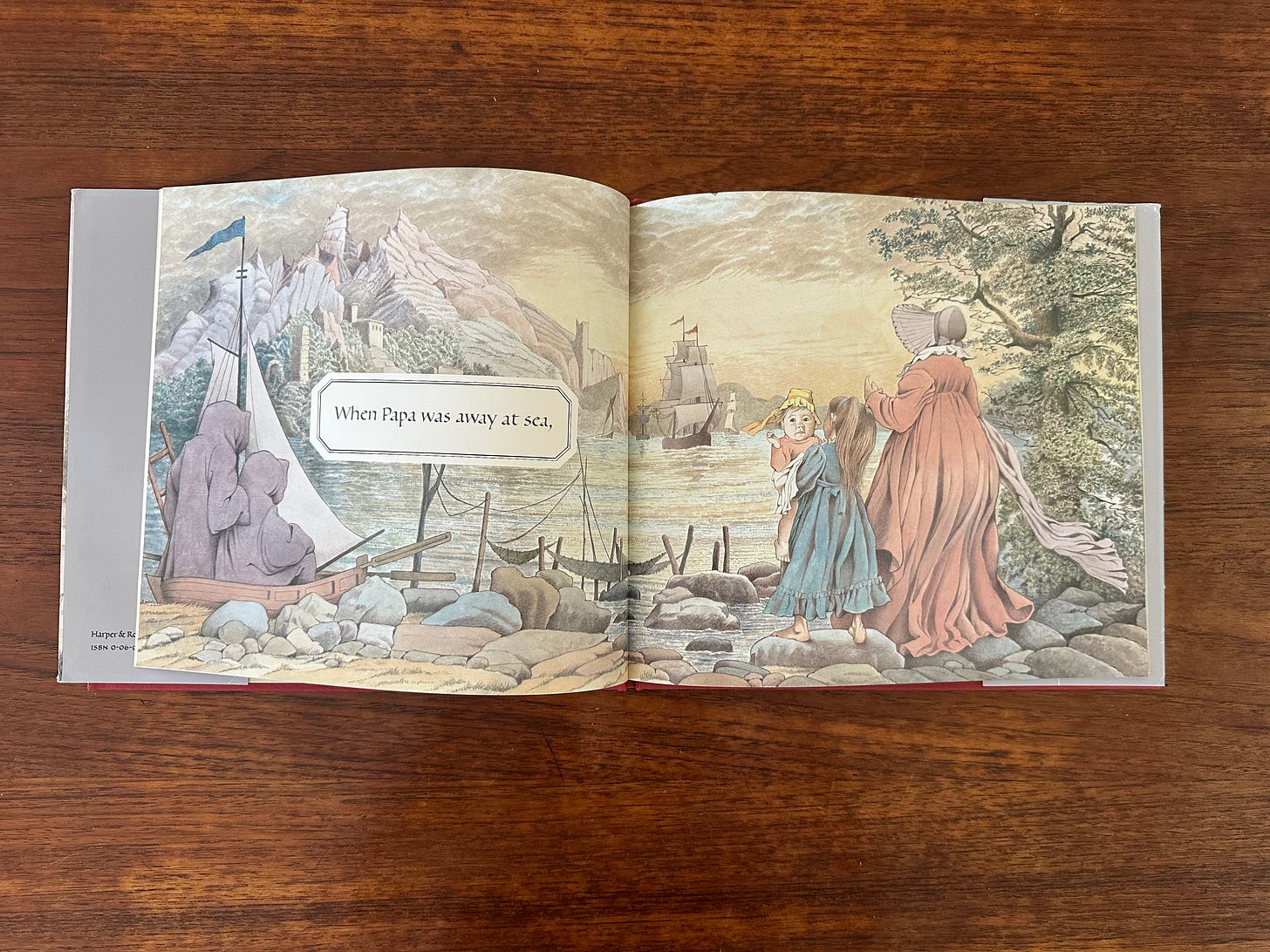

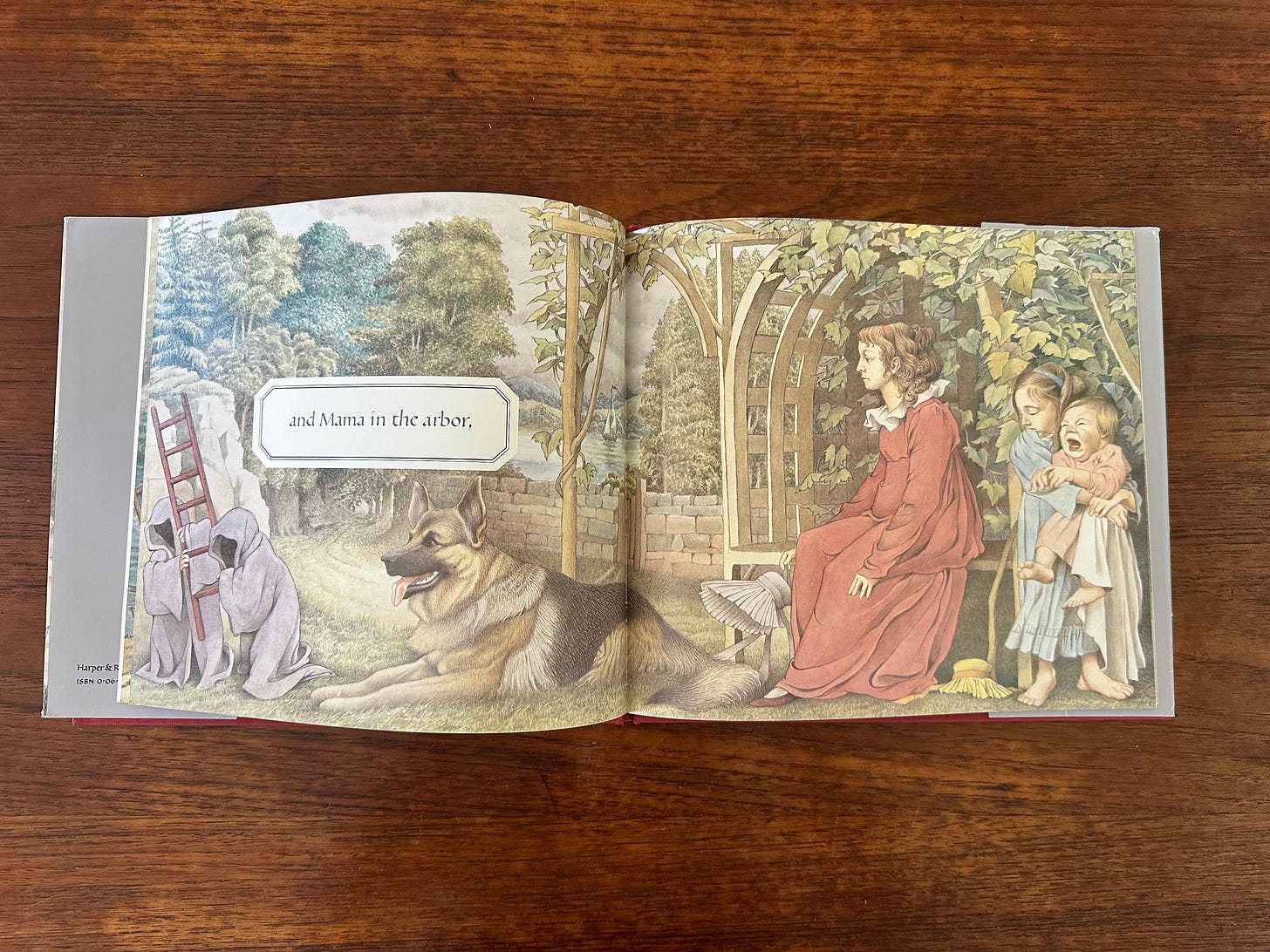

“When Papa was away at sea, and Mama in the arbor, Ida played her wonder horn to rock the baby still—but never watched.”

The last three words “but never watched” sit there ominously at the end of the sentence, especially when you know what lurks behind the next page:

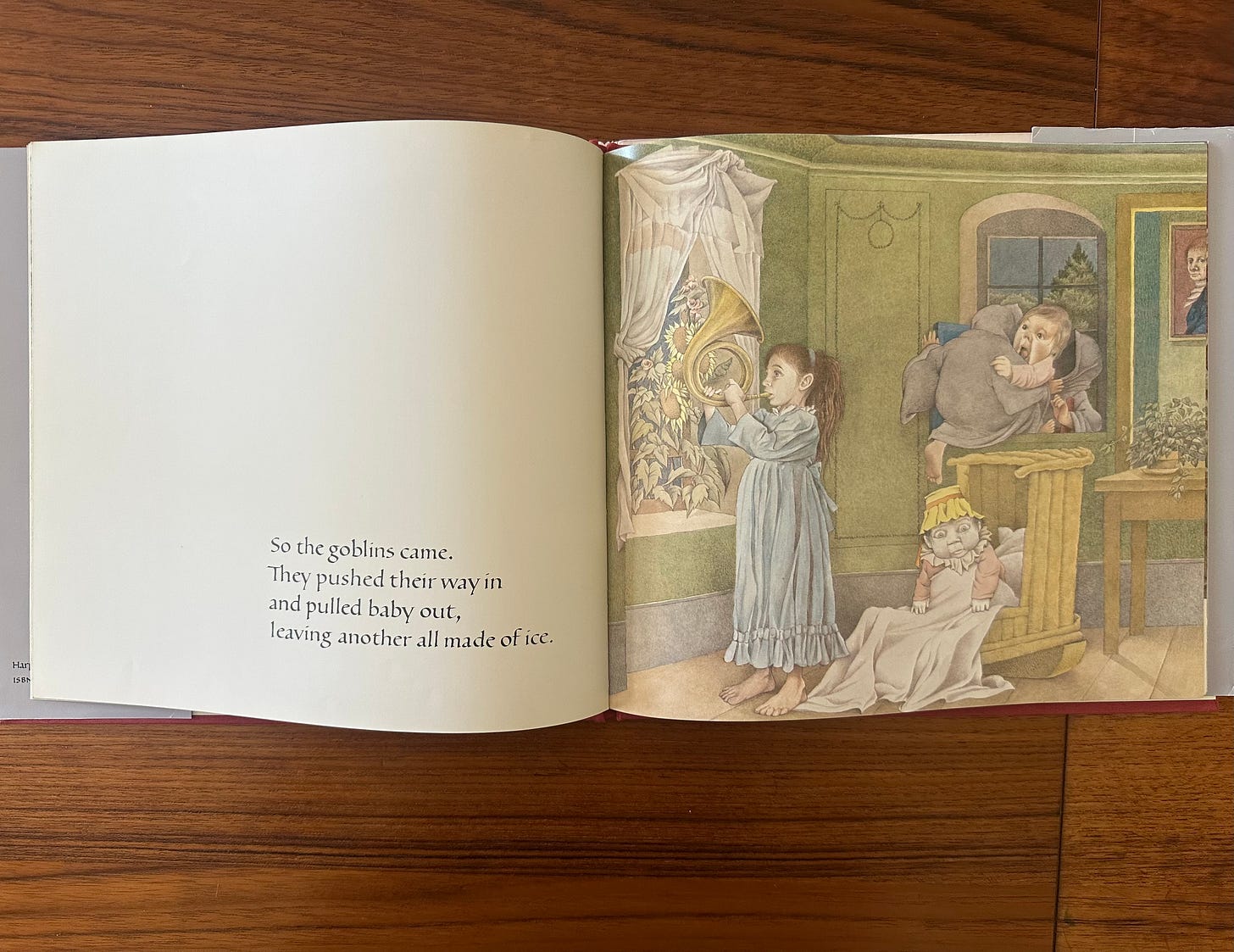

“So the goblins came. They pushed their way in and pulled baby out, leaving another all made of ice.”

(The ice baby’s eyes will haunt me forever!)

But it’s this sentence that leads to one of the book’s most thrilling page turns:

“Now Ida in a hurry snatched her Mama’s yellow rain cloak, tucked her horn safe in her pocket, and made a serious mistake.”

Similar to “but never watched,” those five words at the end of the sentence “and made a serious mistake,” beg you to turn the page!

“She climbed backwards out her window into outside over there.”

I’m captivated by this sentence: its simplicity, its musicality, its deep resounding meaning.

As Sendak described, the book reverberates on all levels, “like a mirror reflection: it’s called Outside Over There, but if you hold the title up to the mirror, so to speak, it says Inside in Here. . . . And one of the clues to the book’s meaning is to reverse everything that happens.”4

“It was not a conceit of language…that’s how I heard it… she does everything backwards, and so the writing came out backwards…it came out that way and it sounded right to me. And then later strange poetry, strange sentence structure, and strange, strange, strange. It’s a whole vision but the words came first.”5

We tend to forget how important the words are in picture books. Sendak felt that the illustrations should act as “backseat drivers,”6 and that language should be number one. I worry that makes it sound like the illustrations are less important, which is certainly not true. But for Sendak, without words there is nothing to build on. His stories didn’t come from sketches or images; they came from an emotional feeling, a connection to his childhood, and the only way he could turn those feelings into a story was to find the right words.

"I don’t think in pictures and I honestly don’t even think in text. It’s a kind of emotional feeling. I mean, they’re almost memories more than ideas, certain needs that have to be expressed, and then they’re very amorphous, they’re very strange. The first step is to find words to embody them. Pictures are as far away from that stage of it as possible, and only when the thing has been written as best I can, then the pictures start coming like Polaroids…I’ve always said this about my work and my own feelings about being in this profession is that I’m in it because of the words. I’m really turned on by words, otherwise I’d be a painter and I can’t be a painter. I have to read before I will see pictures, even my own.”7

It’s taken me a long time to truly appreciate the complexity of Outside Over There. Even as an adult reading it, it can sometimes feel uncomfortable, like I’m looking directly into Sendak’s psyche, and then in a backwards, outside in, kind of way, I’m looking into my own. I recognize my childhood fear of being kidnapped, of losing my parents—especially my dad—who has always been considered old. One day, would he leave me and never come back? Does my older sister resent me for being the baby of the family? For taking attention away from her? As a child, most of these fears were unconscious, but when reading this book, I felt them vibrating right under the surface, inside in here.

10)

In her 1998 article for the London Review of Books, the writer Lorna Sage wrote a sentence about Katherine Mansfield that I can’t stop thinking about:

“In her stories she could pull off the illusionist feat of storing infinite riches in a little room, creating a sense of physical and moral space.”

That could just as easily be said of Maurice Sendak. His books, while small and made for small children, offer us one of life’s greatest gifts: the ability to expand our view of the world, each other, and ourselves. Now that’s magic.

You might also like:

Sendak’s friend, mentor, and fellow children’s book author-illustrator Crockett Johnson helped Sendak land on the word “rumpus.”

Quote from Sendak’s 1990 interview for KCRW radio show Bookworm. It’s an incredible conversation. I highly recommend it—Michael Silverblatt was such an astute reader and thoughtful interviewer.

You can read more about Woolf’s “moments of being” in my article A Shock of Delight.

The Wisdom of Sendak: Children Are Wild, Honest, Immoral Beings written by Buzz Poole (2017)

Another snippet from Sendak’s 1990 interview for Bookworm.

Again, from the Bookworm interview.

From Sendak’s 1977 interview for Profiles in Literature (No.34)

I think this may be the best thing you've written for Moonbow, Taylor -- just excellent, from beginning to end.

A whole dissertation could be written about Outside Over There. Even when I read it now, it's so strange and otherworldly and utterly brilliant, I feel like I can't hold it all at once.

Taylor! Thank you for doing all of this research and writing this essay. You’ve captured so much of Sendak’s essence as a writer and an artist.

I’ve spent the last three years with Sendak and Ursula Nordstrom and 14 other authors and illustrators she worked with (so fun!). My middle grade biography of Ursula, highlighting these collaborations, will be published by Abrams next spring. If you’d like, you can read more about it at my website, named after me.

Ursula discovered Sendak when he was, in his words, “twenty-two-and-a-half.” Eighteen years older than he, she nurtured him through many illustrated books. He even wrote a couple himself before Wild Things, but it was his breakthrough book—for all of the reasons you mentioned. They became good friends.

I had not been a Katherine Mansfield fan before your essay, but I will be checking her out. Thanks again for writing this essay!