MOONBOW IS THREE!

Does critical reaction encourage superior books?

Hip, hip, hooray! It’s a special day for Moonbow! Three years ago, I sent out Moonbow’s first official newsletter! It’s hard to believe that much time has passed. It still feels like I’m just getting started; there are so many things I’ve yet to explore and still hope to create. From the beginning, Moonbow has been much more than just a newsletter. It’s an experimental space that encourages curiosity and discovery and fosters a connection between books and ideas, but, more importantly, between readers.

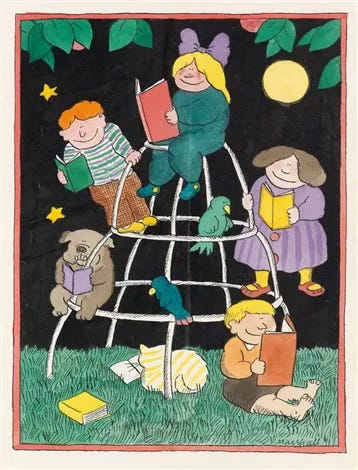

When I had the idea to create a literary publication about children’s books for adults, it was met with skepticism. But I felt passionately that children’s books, especially picture books, were not getting the attention they deserved from most adults. At the time, I was reading more picture books to my kids than ever. It was March of 2022, exactly two years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, and I had just closed my decade-old business. Those two years at home with my kids (who were 6 and 3) were hard and long. Reading helped pass the time and gave us something to look forward to. The outside world was scary and unsafe, but we could freely travel inside the world of picture books; we could experience a vibrant life through words and images. Those deep explorations unearthed a hidden truth about these books that I had previously been blind to (or had forgotten since childhood). They were beautiful, strange, and mysterious. Talking about these revelations with my children made them even more meaningful. They taught me how to read with an open mind and heart.

I couldn’t keep this exhilarating feeling to myself; I had to share it. But how? I’m not an author, illustrator, historian, or any kind of publishing expert; I’m just a reader. Then I realized that kind of thinking is partly why so many adults undervalue picture books. Most of their peers aren’t talking about how these books work (and why they often don’t); they aren’t championing them as sophisticated works of art. At the same time, I knew that to earn this position, I would have to do more than give ecstatic reviews or tell people what they should see. I would have to provide a framework that sets them up to look on their own, not by following rules or teaching techniques but by making compelling connections and offering ideas. This approach is not always easy to follow (even if I get lost sometimes), but I hope my passion comes across and inspires you to pay closer attention to this challenging and worthwhile art form.

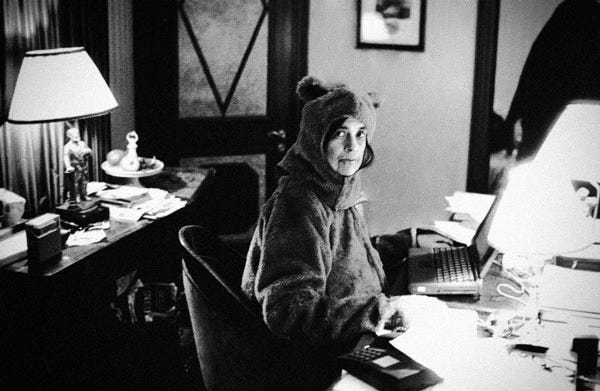

When I doubt the process, I turn to Maurice Sendak’s Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books & Pictures (1988)—one of the best books on children’s literature I’ve ever read. Sendak was not only a genius children’s author and illustrator, he was also an avid reader and astute critic. The collection includes his illuminating essays on Randolph Caldecott, Beatrix Potter, Walt Disney, Tomi Ungerer, and others. There are also a few of his speeches and interviews, which have become guideposts for how I think and write about picture books.

Since the book is not easy to find (I don’t think it’s in print anymore), I thought I would share a section from Sendak’s 1977 interview with Walter Lorraine, where he shares his philosophy on making and evaluating picture books.

Lorraine: How would you define a picture book?

Sendak: A picture book is not only what most people think it is—an easy thing to read to very small children, with a lot of pictures in it. For me, it is a damned difficult thing to do, very much like a complicated poetic form that requires absolute concentration and control. You have to be on top of the situation all the time to finally achieve something that effortless. A picture book has to have that incredible seamless look to it when it’s finished. One stitch showing and you’ve lost the game. No other form of illustrating is so interesting to me.

L: Was there a time when, in your opinion, picture books were better than today?

S: Yes. Of course there was Wanda Gág. There’s always Millions of Cats. And we did have a glorious period in the 1950s and 1960s. American illustrators were tremendously stimulated by work coming from abroad. Remember the fifties, when Hans Fischer’s books were first published here and Finders Keepers by Will and Nicholas won the Caldecott? I remember my excitement when I first saw it. It had an international flavor, which was something new in American picture books. And there was Tomi Ungerer, and a lot of others just beginning. We suddenly began to look very European. It was the best thing that could have happened to us—we looked terrific!

L: Do you think there is a lack of talent in picture books today?

S: I did think that for a long time. But since I’ve been teaching I know it’s not true. I’ve had the pleasure of working with some very talented, even brilliant young people. And I can say without hesitation that a few of my best students are ready to be published. They have an ethical approach toward the picture book, a vital and serious approach; and it has made me realize that my original view that talent wasn’t there was probably false.

If talent is around but nobody is using it, what is wrong?

It seems to me that the system is at fault. If you speak to publishers, every one of them will say, “We’re always looking for new people.” Then why aren’t they being published? I’ve had great difficulty in placing some of my gifted students. What’s the risk? It seems to me that publishers are less ambitious than they used to be, in general less brave, less willing to take risks. If you say this aloud, you get the standard response: “But we are publishing young people.” Well, where are they?

My suspicion is that publishers are afraid. In the old days they did take chances. Nothing’s happening now. I’m nearly fifty and when I turn around, I see very few young people climbing up the mountain. When I was young, in the fifties, we were given all the encouragement in the world.

L: Do you think that critical reaction today encourages superior books?

S: No. There are exceptional publishers, and there are a few exceptional critics—some very few exceptional critics—who take the trouble to evaluate a children’s book in an intelligent way. They’re not burdened with boring, tedious attitudes, such as whether a book is good for kiddies. They take an overall view of it aesthetically. Does it stand up as a work of art?

Speaking from my own personal experience, I have not learned anything from reviews of my books. And I’ve rarely seen reviews of other people’s books that I thought did justice to a book’s special qualities. Yes, there are some intelligent reviewers out there who can distinguish between the real and the phony. They take the larger view and escape the fatal Kiddiebooklanditis that most reviewers suffer from. But they are exceptional, very exceptional. Too often, children’s books are judged by whether they conform to well-meaning but misguided rules about what children ought or ought not to be reading.

( “We’re shaping taste” Maurice Sendak interview for CBS News. 1973)

L: Do you think critics should react differently to the illustrations in picture books?

S: I think they should try to learn what picture books are all about. There is some fine mystery in this difficult form, a mystery that is the artist’s business. What I’m objecting to is that picture books are judged from a particular, pedantic point of view vis-à-vis their relation to children—and I insist that a picture book is much more.

When people review our books, a collision inevitably occurs with preconceptions concerning children. There is a standard theory about childhood that everybody works from, and critics check whether a picture book has followed the “rules” about what is right for children, or what we think is right and healthy for children. This comes into conflict all the time with those things that are mysterious. Children are much more catholic in taste; will tolerate ambiguities, peculiarities, and things illogical; will take them into their unconscious and deal with them as best they can.

The anxiety comes from the adults who feel that the book has to conform to some set ritual of ideas about childhood, and unless this conforming takes place, they are ill at ease. An unavoidable conflict occurs because the artist cannot go by any specified rules. The artist has to be a little bit bewildering and a little bit wild and a little bit disorderly. That’s the art of being an artist. Artists run into difficulty because they’re dealing with our most upright, uptight business, which is the industry called childhood.

Most people are out to protect children from what they think is dangerous. Serious artists have the same concern. Their work, however, may not conform to what the specialists think is right or wrong for children. The artists are going to put elements into their work that come from their deepest selves. They draw on a peculiar vein of childhood that is always open and alive. That is their particular gift. They understand that children know a lot more than people give them credit for. Children are willing to deal with many dubious subjects that grownups think they shouldn’t know about.

If a book doesn’t follow the course of what a childhood specialist considers right, then it’s a bad book for children. So picture-book people are more easily condemned than almost any other artists in creation because we’re dealing with such a volatile subject—children. We must protect the children, and yet children are unprotected in every other way. No one protects them from terrible television. No one protects them from life because you cannot protect them from life, and all we’re trying to do in a serious work is to tell them about life. What’s wrong with that? They know about it anyway.

(Maurice Sendak on Charlie Rose. 1993)

L: What should we look for in a picture book?

S: Originality of vision. Someone who has something to say and a fresh way of saying it. Do not look for pyrotechnics, for someone who can make a big slambang picture book out of very little. Look for the artist who thinks idiosyncratically.

L: Can you define what a picture book is for you?

S: Well, I think I have; it’s everything. It’s my battleground. It’s where I express myself. It’s where I consolidate my powers and put them together in what I hope is a legitimate, viable form that is meaningful to somebody else and not just to me. It’s where I work. It’s where I put down those fantasies that have been with me all my life, and where I give them a form that means something. I live inside the picture book; that's where I fight all my battles, and where I hope to win my wars.

Happy three years, Taylor! Moonbow and you are very special — you give me hope that adults can learn to see picture books as an art form rather than a lesson. And you remind me that the best storytelling risks are worth fighting for 😊 When I open moonbow, I feel nourished in mind, body, and spirit. My brain and heart feel more alive and connected to each other and the world. Thanks for your words and hard work!

Congrats, Taylor! Can’t wait to see what comes next for Moonbow.