Sometimes Doing Nothing Is Not a Dumb Thing

Thoughts on summer break, reading, writing, and not writing

I’m sitting outside at a cafe on a pleasantly warm afternoon. A mother and daughter are sitting at a table next to me. The daughter is younger and seemingly much calmer than my two children (she looks around 4). The mother is looking intently at her cellphone, engrossed—perhaps reading an important email or booking an urgent appointment. The daughter is swinging her feet back and forth, letting her toes gently kiss the ground. She is subtly vying for her mother’s attention. She softly taps her tiny fingers, one by one, on the table. The mother stays affixed to her screen. The daughter then quietly asks her mother if she remembers the story about the spider on the wall. Still nothing. The mother doesn’t hear her (or pretends not to). The daughter starts to sip from the plastic straw of her chocolate milk box. She sips and sips until there is nothing left to sip but air and noise. When that doesn’t work, she gets up and announces to her mother that she is going to throw away her chocolate milk box. It’s a bit awkward. Can the mother sense me watching? She dramatically stretches her arm out straight away from her chest and lifts the phone up directly in front of her face. A performance? Still, the daughter will not be defeated. She tries again. This time announcing proudly that the chocolate milk box is now officially in the trash. Without looking up, her mother says, “Good job, honey,” while furiously typing away on her little glass machine. The daughter sits back down and notices that she has my attention. She cracks a small smile. I return it, then quickly pretend to be busy on my laptop. The irony. What does she think of us adults always staring at our screens? Does she think about it? Or is this the only world she knows? And her mother—she is not a bad mother. She is all of us. She is me. I came to this cafe because my children were vying for my attention, as they have for most of the summer, but I have other things I want to pay attention to, like someone else’s kid.

Summer break is difficult for me. (I’ve written about this many times.) I think it is for most parents, whether your kids are busy with camps or not. My kids did zero camps this year. We wanted to see if we could pull off an old-school summer (aka save money). Older generations (mine included) have romanticized retro summers, and while my kids did experience some classic moments—jumping through sprinklers, making sandcastles on the beach, playing outside in the neighborhood until dark—most of the time, they were hot, bored, and grumpy, which is how I remember feeling during summer as a kid.

Another reason summer break sucks is it reminds me how hard writing is—not that I ever forget. But when you spend most of your time not writing, it’s easy to convince yourself to never do it again. I’d much rather read. I write because I read, not the other way around. It’s as if all that information, all that feeling and thinking, needs an outlet. I could write privately, but it’s more fun—and potentially more considered—when there’s an audience. Except an audience often requires growth. The bigger the audience, the “better” you are perceived to be at your craft. But what if the goal isn’t better? What if the goal is pleasure?

I write Moonbow to share my love of reading and thinking about children’s literature, the pleasure of it. These acts can’t always be expressed in a compressed timeframe. I constantly struggle to maintain a consistent and frequent publishing schedule. Would I be more “successful” if I did? The Substack experts seem to think so. I’m not convinced.

The origins of the word “successful” (n.) + -ful (1580s) meant “of persons or actions achieving or resulting in the accomplishment of what is intended or desired.” It wasn’t until the 1870s that it started to mean "wealthy, resulting in financial prosperity.”1 We often consider someone successful when they achieve both, but most of the time, especially in the arts, the two results are at odds with each other. It can be discouraging. What I tell myself (and those who ask me for Substack advice) is to develop and stay true to a clear vision. Why do you want to write a newsletter? What do you hope to achieve? Your goals may include financial success, but is it the main reason you’re here? There is no judgment. Everyone has different goals. When I start to lose sight of my vision, I go back to the beginning. Why was I originally excited to write here? Can I still hold on to those feelings? Can I tune out the noise? So far, I’ve been able to reset and refocus, but it’s getting harder.

Part of the pleasure of writing Moonbow is not writing Moonbow. I don’t mean there is pleasure in procrastination (although, that can sometimes be true). I mean there is pleasure in the formation of thought, in being challenged, and expanding your understanding of a story, a sentence, a word, of humanity, of yourself. This sounds grandiose, but for me, the feeling is usually small, and then expands, or, more often, disappears. It develops in the strange, fizzling, fleeting space of possibility right before writing something, when it’s just me alone with the texts—simply being with them. It’s a fantasy filled with tangential connections, little phrases, and fuzzy images scribbled hastily on receipts and scattered on Post-It notes. These wild, half-formed thoughts are surprisingly buoyant. They push me forward toward some unknown destination. I float along happily. It’s only when I try to dock them and try to turn them into something concrete and polished that they deflate and I begin to sink. When this happens, I become depressed, and swear off writing forever. But then a bubbling new thought rises up, and I’m propelled to start the journey all over again.

Sometimes it’s not a dumb thing,

Sometimes it is really something,

Doing no-thing.

I’ve been writing publicly for almost 20 years, but it wasn’t until I started Moonbow that I discovered how to write and what writing can do (an ongoing process). Each time I start a new essay, I’m faced with the limits of my abilities, countless distractions, and wandering thoughts. It takes a bit of naiveté and an enormous amount of dedication to get through it—which is why I sometimes don’t.

Even though doing “nothing” is an essential part of my writing practice, eventually I try to do something to achieve finished results. Otherwise, it would all feel like nonsense. The hard parts make it real. I’m not alone in this experience. Writers have complained about the pains of writing for forever.

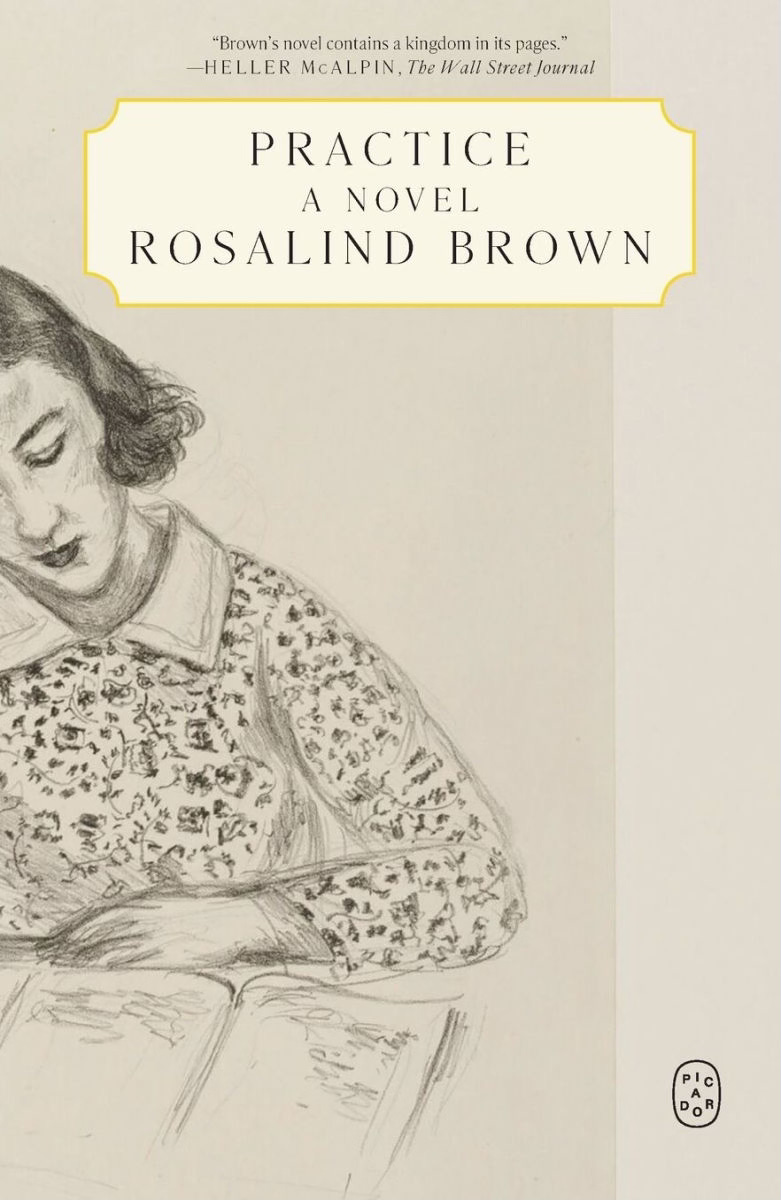

I was recently reminded of this while reading Practice (2024) by Rosalind Brown, a slim, incandescent novel that follows a day in the life of Annabel, an Oxford student writing an essay on Shakespeare's sonnets. Desperate to meet her tight deadline, she tries to follow a meticulous routine—solitude, reading, walking, yoga—but despite her best efforts, she cannot stop her mind from wandering, and is constantly distracted by all the non-events that make up a life. Annabel’s keen sense of attention is helpful to her writing practice but it’s also a hindrance—her thoughts, feelings, observations, and bodily urges are intensely vivid and absorbing.

In one of my favorite passages, Annabel is determined to finally make progress. She spreads out six pages on her desk. “Six tight poems for her to lick with her mind in a long slow lick right up the spine of each one.” Even though she’s never written a poem, she thinks maybe she wants to be a poet—one who writes small, opaque, complex poems about nothing in particular “producing not so much a meaning as an effect," but then she has a new thought, “maybe it is a poem she wants to be. A strange small one like Emily Dickinson, or an expansive glittering one like Gawain the poet, or a breathing questioning one like Keats. Or even a poem just held in the memory, intact with its commas and colons, not spoken but silent, or just murmured, like rebellious truths are murmured when backs are turned.”

Yes, she wants to be a poem.

I, too, want to be a poem. But there is a difference between wanting and being—and that disconnect often holds me back.

After reading Practice, I was inspired to read more by Brown. In her story, Discourse to Self2, she writes:

“Rather than announcing various refusals in the name of your own well-being, you would do better to find things to say yes to. Sometimes do make yourself tremble by agreeing to everything that is suggested, tremble at everything you yourself have the potential to do. Then you can reinstall the proper curtains which divide the possible from the actually impossible, and perhaps choose a new pattern or style for them or insert additional pleats where there were no pleats—though all the same, remember you are not designing a hotel, you will have to live here.”

I make a lot of excuses in defense of my well-being, but now that summer break is over, and my next chapter awaits, I plan to try something new:

I will say yes more. I will make myself tremble with the pleasure of my potential.

If you enjoy reading Moonbow and want to support my work:

Upgrade to a paid subscription

Share Moonbow with someone who might enjoy it too

Give this post a like or leave a comment

Check out the archive

Follow me on Instagram

And if you’d like to work together, you can email me at taylor.sterling@taylor-sterling.com

Thanks!

The first known origin of the word “successful” was in the 1580s (Online Etymology Dictionary).

Brown, Rosalind. Discourse to Self. Harper’s. November, 2024 issue.

Taylor - thanks for another thoughtful, delicious post as always. I keep returning to your Substack because of its long form. I like having to take my time as I take in your words. It feels a bit like resistance to what the loud! quick! viral! nature of social media and similar platforms want from us. I appreciate your pace and your approach.

In the interest of reminding yourself why you started Moonbow in the first place, I'm a recent-ish subscriber and LOVE your newsletter. I don't have kids and hadn't given a thought to children's books. I learn so much from your posts. And I like that they are infrequent, because when I do receive something from you, I know it will be thoughtful. And they don't pile up in my inbox until I have time to read them all at once. :)