Getting to Know Shawn Harris Pt. 1

The author-illustrator shares five books that inspired his latest picture book “The Teeny-Weeny Unicorn.”

Today’s special feature with children’s author-illustrator Shawn Harris is a two-parter. There was too much good stuff for one newsletter! In part one, Shawn shares five books that inspired his latest picture book, “The Teeny-Weeny Unicorn.” In part two (going live tomorrow), Shawn and I talk in detail about these books and his own. If you love picture books, you won’t want to miss it. Warning: This is a long-form email. You may have to click the gray dots at the bottom to read the full article. Thanks!

Saturdays were a big deal when I was a kid. I’m sure they still are to kids today but for different reasons. For me—a child of the 1980s—Saturdays were the only day I was willing and eager to wake up early. That’s because the event of the week was happening: Saturday-morning cartoons. It felt simpler back then. There weren’t endless YouTube videos to choose from, and you couldn’t binge-watch an entire season of your favorite TV show. The toughest decision we had to make was between Lucky Charms and Frosted Flakes.

It wasn’t just the cartoons that made this time special; it was also the experience: the ritual of waking up (usually without your parents, who were using the cartoons as a babysitter so they could sleep in), grabbing a blanket, and cozying up on the couch with your favorite sugary cereal. Even if you were alone, there was comfort in knowing that kids everywhere were doing the exact same thing: this was our time. The predictability of this weekend routine provided comfort in an unpredictable world. Kids have little autonomy over their days; they’re constantly being told where to be and what to do, but for a few hours every Saturday morning, kids were in charge.

Fast-forward to March 2020. COVID-19 has swept the world, shutting down offices and schools. Suddenly, there’s no clear delineation between the week and the weekend, and there are no communal experiences; everything feels unpredictable and scary. But then came “Mac Barnett’s Book Club Show.” Every Saturday at noon, the children’s author Mac Barnett hosted a live event on his Instagram. Children (and parents) tuned in from around the world to listen to him read picture books, tell jokes, and answer questions from fans (affectionately called “Club Heads”). The weekends had a purpose again. There was something to look forward to. And the toughest decision to make was what hat to wear because everyone was encouraged to wear a hat, even if that hat was a shoe or the leftover crust from your sandwich. As Mac always said, “It’s a hat if you believe it!”

As the mom of two young children (then six and three), I was incredibly grateful for the Book Club Show, as were all the parents tuning in. We felt like we were a part of something truly special that would (hopefully) never happen again. And for those of us who watched Saturday-morning cartoons as kids, the Book Club Show evoked a sweet nostalgia. We weren’t just reading books together; we were part of a live theatrical experience.

Mac often hosted remote guests on his show, like children’s authors and illustrators Carson Ellis, Christian Robinson, and Jon Klassen, but it was his trusty sidekick, best friend, and racquetball enemy, Shawn Harris, who made the most appearances. Mac and Shawn have been friends since they were 7 years old. You can’t talk to one of them without the other coming up in the conversation. You get the sense that they’re more like brothers than best friends. They’re incredibly close.

As a budding children’s book enthusiast, I was well aware of Mac Barnett’s books, but I didn’t know Shawn Harris. At the time, Shawn had illustrated a few picture books: Her Right Foot (2017) and What Can a Citizen Do? (2018), both written by Dave Eggers and Everyone’s Awake, written by Colin Meloy, which came out in March 2020, a strangely coincidental time for a book about a family stuck in a house not being able to sleep. Despite his obvious talent, Shawn wasn’t on my radar. However, the moment Shawn began joining Mac on the show, he became impossible to ignore.

Mac and Shawn were also ‘80s kids (the three of us were born in 1982). Like me, they were obsessed with Saturday-morning cartoons and decided to create a Saturday cartoon of their own, a live cartoon, “The First Cat in Space Ate Pizza.” Every Saturday, the Book Club Show would feature a new episode of “The First Cat,” which Mac and Shawn performed live over Zoom. It was a thrilling production that left us Club Heads eager for more. We fell in love with the characters, but more than that, we felt like we were a part of the story.

Making children feel like they’re a part of the story is what Shawn does best. His mother was a children’s art teacher, and he grew up making art with whatever materials were on hand, a formative experience that continues to influence Shawn’s approach to making books. He draws using materials that his readers usually have at home, allowing them to recreate art in a similar style to his. He also writes stories that draw readers in. His debut picture book as author and illustrator, Have You Ever Seen a Flower? (2021) not only asks readers if they’ve ever seen a flower but if they’ve ever been a flower.

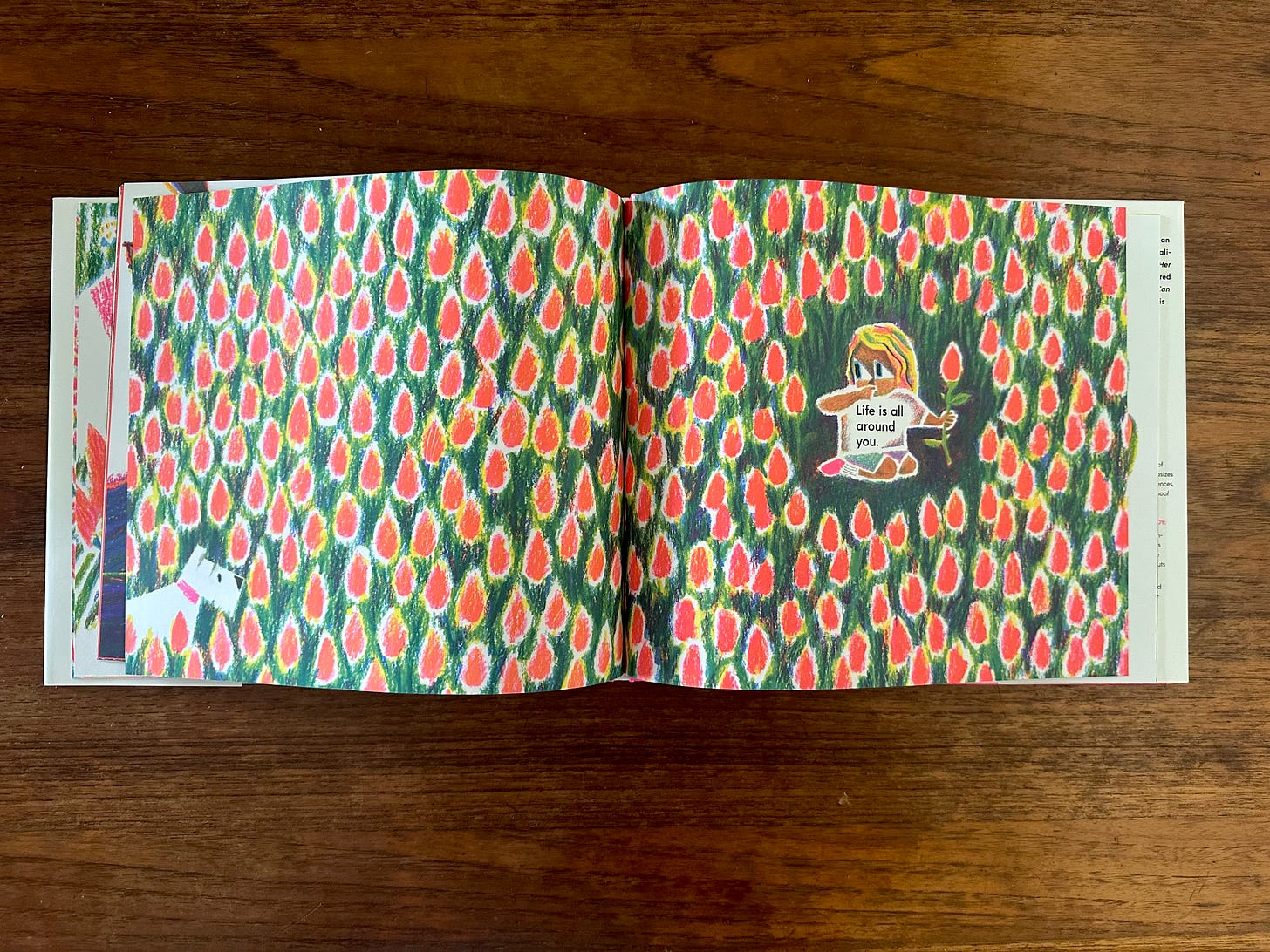

It’s a psychedelic story of a young child’s journey from a drab, gray city into a hyper-colored fluorescent flower meadow. But it doesn’t end there. Like many great children’s stories, there’s a secret door, except instead of a door, it’s a flower, and instead of tumbling down a rabbit hole into Wonderland, it’s a portal into the child’s inner world, a sensory experience of self-discovery (which, if you think about it, is what all the secret portals are).

In one of my favorite sections of the book, it asks, “Have you ever felt a flower? Do a flower petal’s veins feel like the veins beneath your skin? Have you ever pricked your finger or fallen on your knee and seen the brilliant color of your life?” Then you turn the page to see a startling full-bleed spread, ablaze in a crimson hue. “Life is inside you. Life is all around you.” The book speaks to a child’s enigmatic relationship with the natural world. It’s a poetic reminder that they, too, are nature. As the author Hermann Hesse said, “Your soul is the whole world.”1

The book is a dazzling object, richly illustrated entirely with neon-colored pencils. It’s a true feat in bookmaking, and deservingly, it won a Caldecott Honor. But before this book went full bloom, there was A Polar Bear in the Snow (2021), the delightful first picture book Shawn and Mac made together after trying for over a decade. Soon after that, they announced that they were adapting their fan-favorite Saturday cartoon, The First Cat in Space Ate Pizza, into a graphic novel series. In just four years, Shawn went from relatively unknown to an award-winning, best-selling author-illustrator. But overnight success is the stuff of fairy tales. Shawn tried for over 10 years to break into publishing while he was busy doing other things (like touring the country with his pop-punk band The Matches!)2. He was determined to land Steven Malk of Writers House as his literary agent. Malk, a mythical creature of kid lit world, has an impressive roster that includes many of the best authors and illustrators, including Shawn’s BFF, Mac. Looking at the innovative books and outstanding talent that Malk champions, I can’t help but think he’s this generation’s Ursula Nordstrom.3 Eventually, Shawn’s patience and persistence paid off. Malk is now his agent and good friend.

Fairy tales and mythical beasts, especially unicorns, are ubiquitous in children’s books. Unicorns no longer have to be lured from magical forests and captured by a naked virgin—they’re everywhere!—and have been used for every trope imaginable. So when Shawn announced his newest picture book, The Teeny-Weeny Unicorn (2024), I was surprised. A unicorn book, really? But now that I was fully aware of Shawn’s talent, I knew it would be anything but typical. It opens with, “Once upon a time, in a land where horses were mythical beasts, found only in the pages of books for children, it was common to see a unicorn. But not one this size.” Immediately, we’re primed: this is an unusual unicorn.

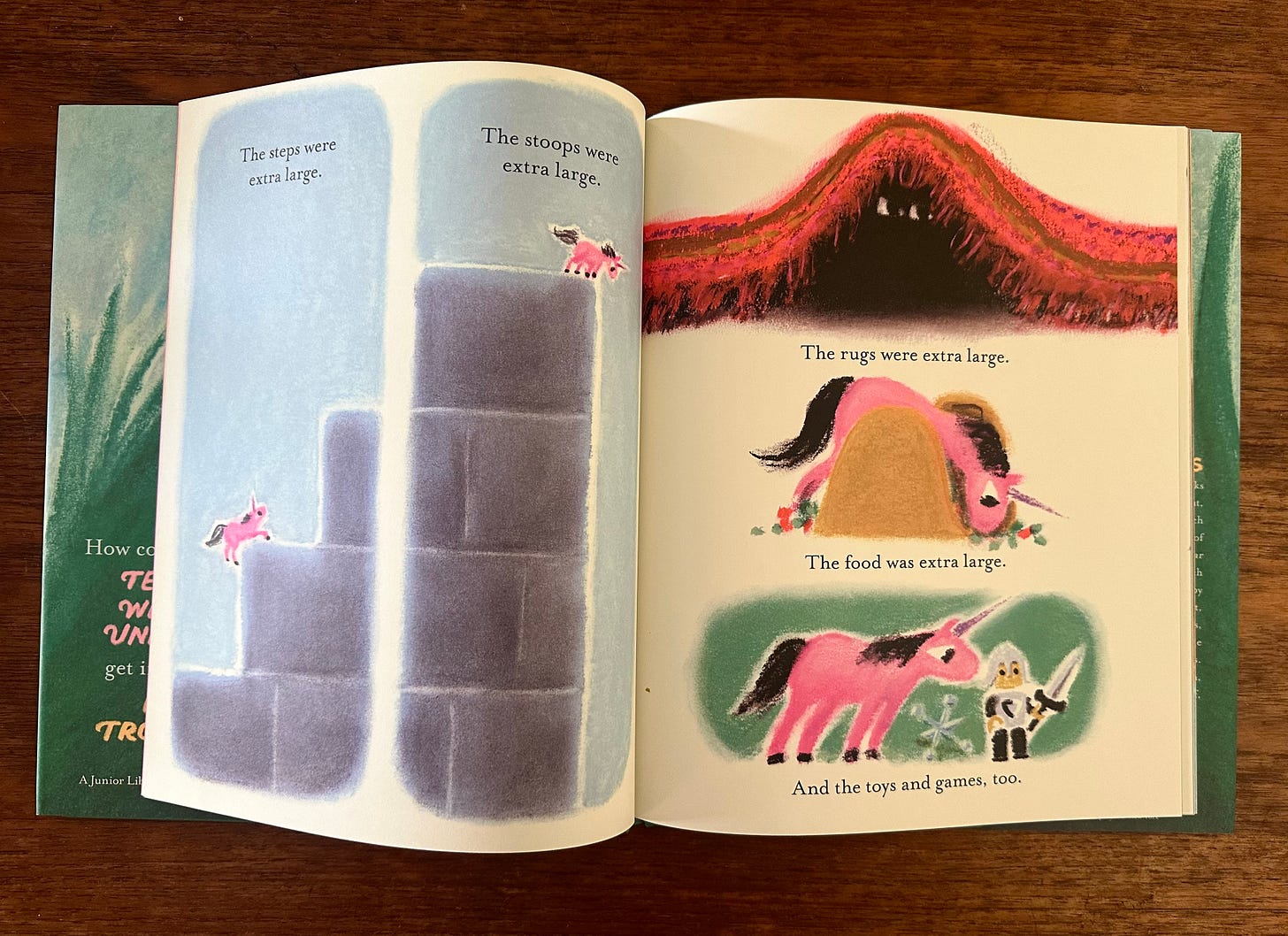

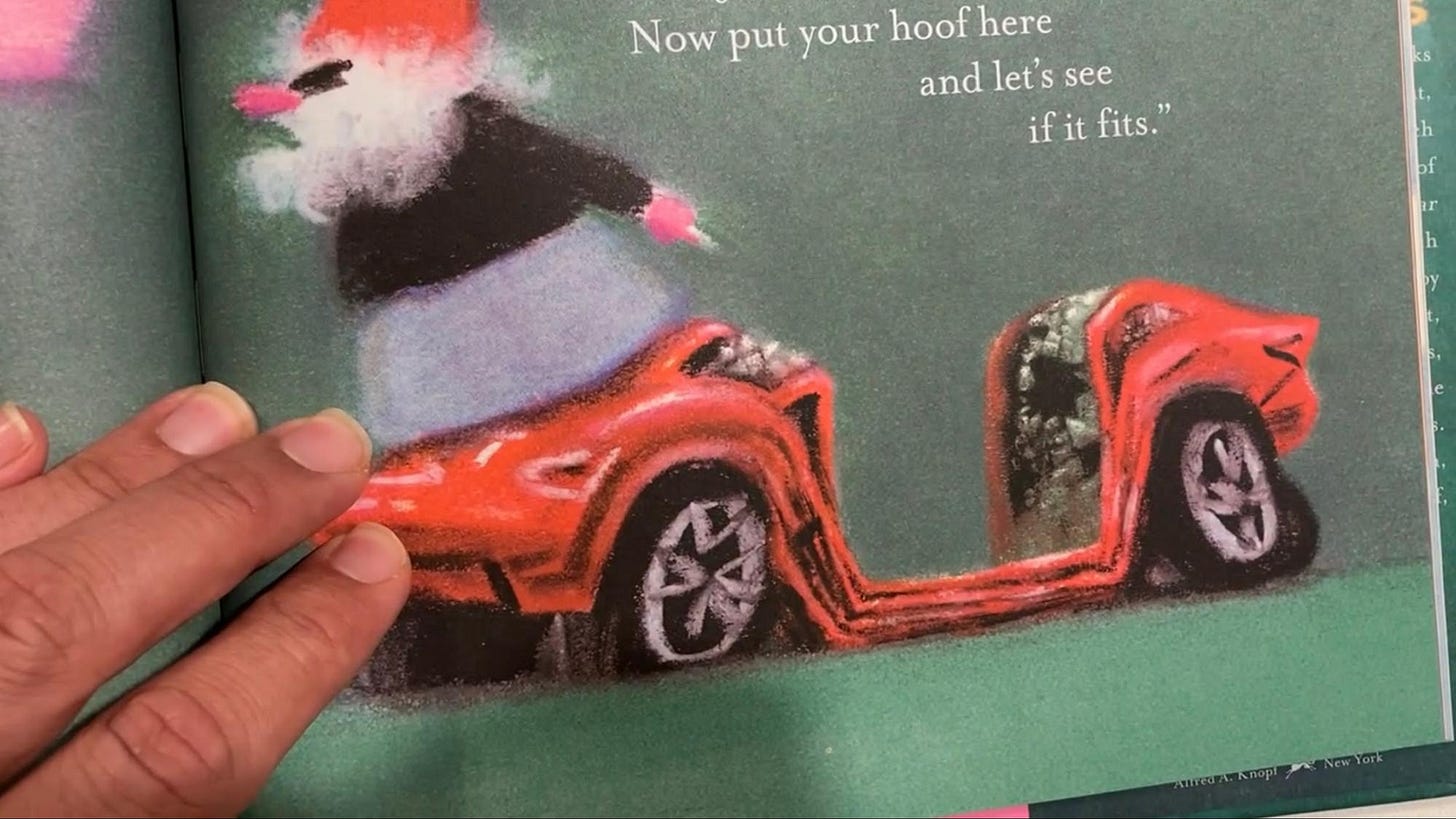

In this tiny unicorn’s world, stairs, rugs, food, and toys are all too big for him, and his brother and sister, both bigger in age and size, won’t let him play with them. Forlorn, the teeny-weeny unicorn does what all good fairy tale protagonists do: he flees into the forest (in his case, a garden), where he meets a gnome who’s even teeny-weenier than he is. The unicorn is shocked to discover he’s the culprit of a crime: he’s unknowingly smashed the gnome’s shiny red sports car with his “giant” hoof. Salty and surprisingly street-smart, the gnome insists the unicorn repay her for his big mistake, and the two of them set off back to the castle. The story gallops along at a propulsive page-turning pace with funny one-liners and vibrant pastel illustrations that pack their own punchlines.

It’s hilarious and heartwarming and acknowledges a feeling that all kids have experienced: being too small. Too small to ride the roller coaster, too small to slam dunk, and too small to play big-kid games. But being small is relative, and sometimes, it takes something big to change perspective. “We are all teeny-weeny. We are all giants. And we are all the right size.”

On their most recent book tour for The First Cat in Space and the Soup of Doom, Shawn and Mac coined it as a “LIVE 360° THEATRICAL SPECTACULAR!” (It was; I was there.) But the same can be said about reading Shawn’s books: we think, we laugh, we sing, we dance. It’s an immersive experience between adults and children. We’re a part of the story—although there’s no question—the kids are in charge.

Wow! I didn’t know I was going to write such a long introduction, but Shawn’s books mean a lot to my family, which is why I’m thrilled to have him on Moonbow to discuss The Teeny-Weeny Unicorn and five books that inspired him while making it.

Take it away, Shawn!

Shawn:

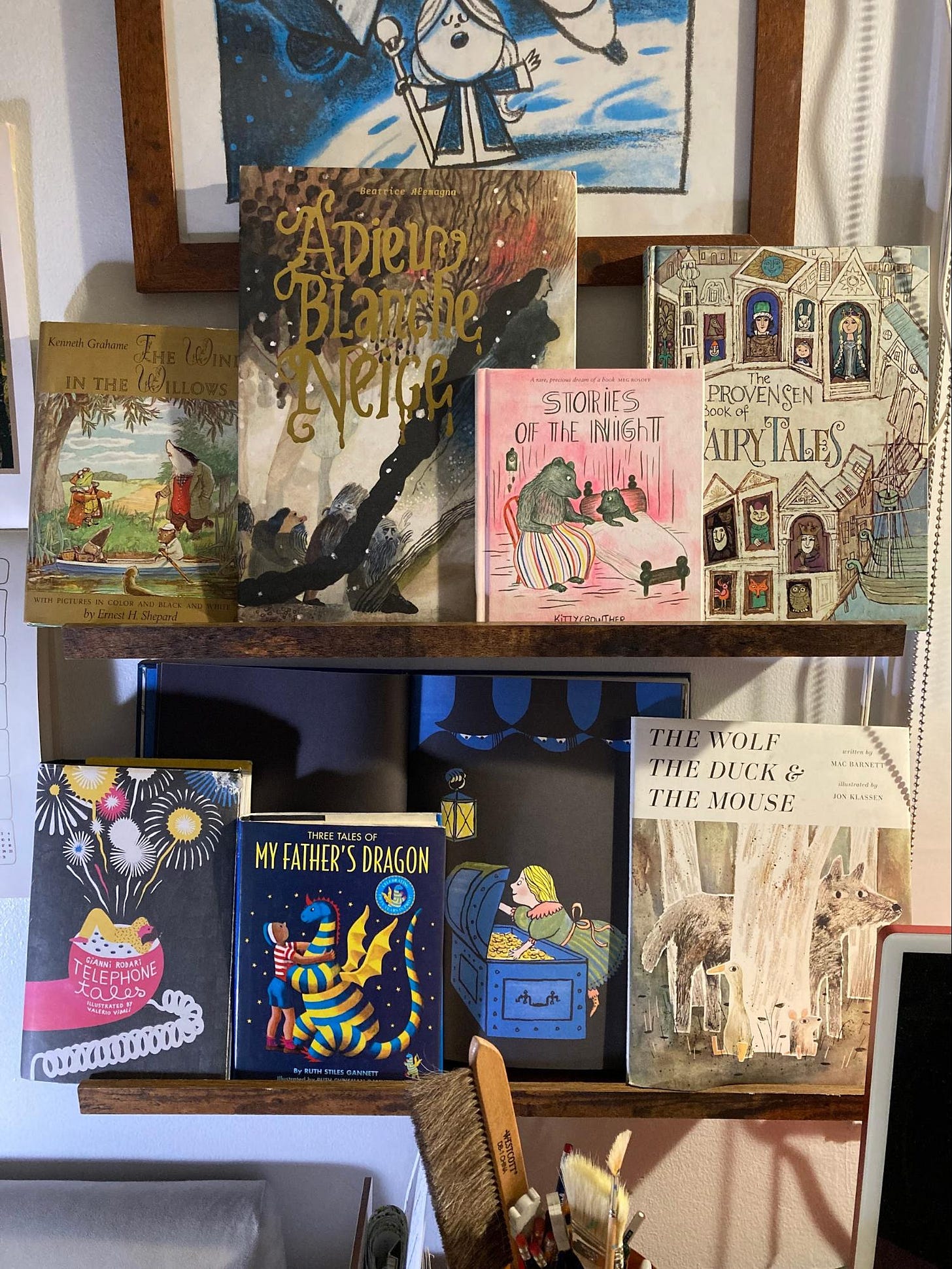

My favorite part of making a book comes before I write or draw much at all—I’ll have some foggy idea that feels like it might be worth pursuing, and I go prowling along my shelves for books that might help me map a path through the haze. I put these books on a special shelf overlooking my desk, and while I work, I pull them down, clip them open to certain pages, and refer to them like a compass to keep my bearings. Here are the books that shaped my latest picture book:

And here’s me, attempting to look lost in the lawn, holding a copy of The Teeny-Weeny Unicorn.

Back to the shelf! I’ve winnowed my thoughts down to five of these books that inspired me most, beginning with:

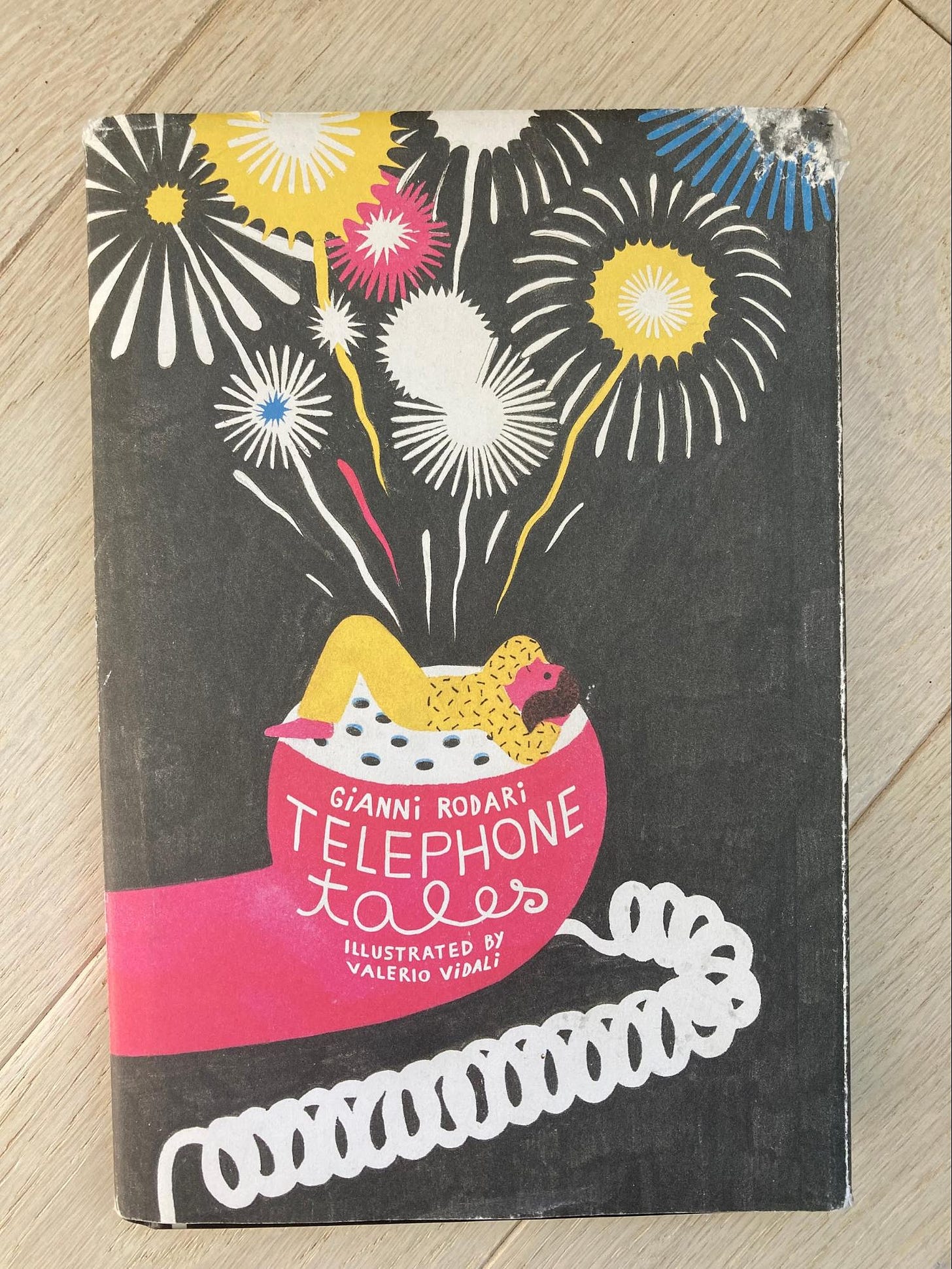

Telephone Tales, written by Gianni Rodari, illustrated by Valerio Vidali (2020)

The excellent marker-drawn cover caught my eye faced-out in a new releases display, but these short stories by Rodari have apparently been well read by children in Italy for decades. Since this edition of the book is a compendium of Rodari’s work, there is just one illustration to accompany each story, and it struck me that many of the stories would be the perfect text to illustrate as individual picture books. However, I wasn’t the only illustrator thinking this—my Google search revealed another of my favorite picture book makers, Beatrice Alemagna, was already at work illustrating a couple of my favorites from the book Telling Stories Wrong and A Daydreamy Child Takes a Walk. So that idea being scratched, I set about puzzling what it was I liked about Rodari’s stories so much; his use of “Once upon a time” and other folktale signifiers like magicians and kings, are often coupled with modern things like machines and rifles and ice cream. (Is ice cream modern?) The resulting sense is that his tales may, at any moment, flip a hairpin turn at top speed. Maybe, I thought, I should try my hand at my own telephone tale. Around this time, I saw a picture of some horses looking down at a tiny horse and just loved the pathos of the image:

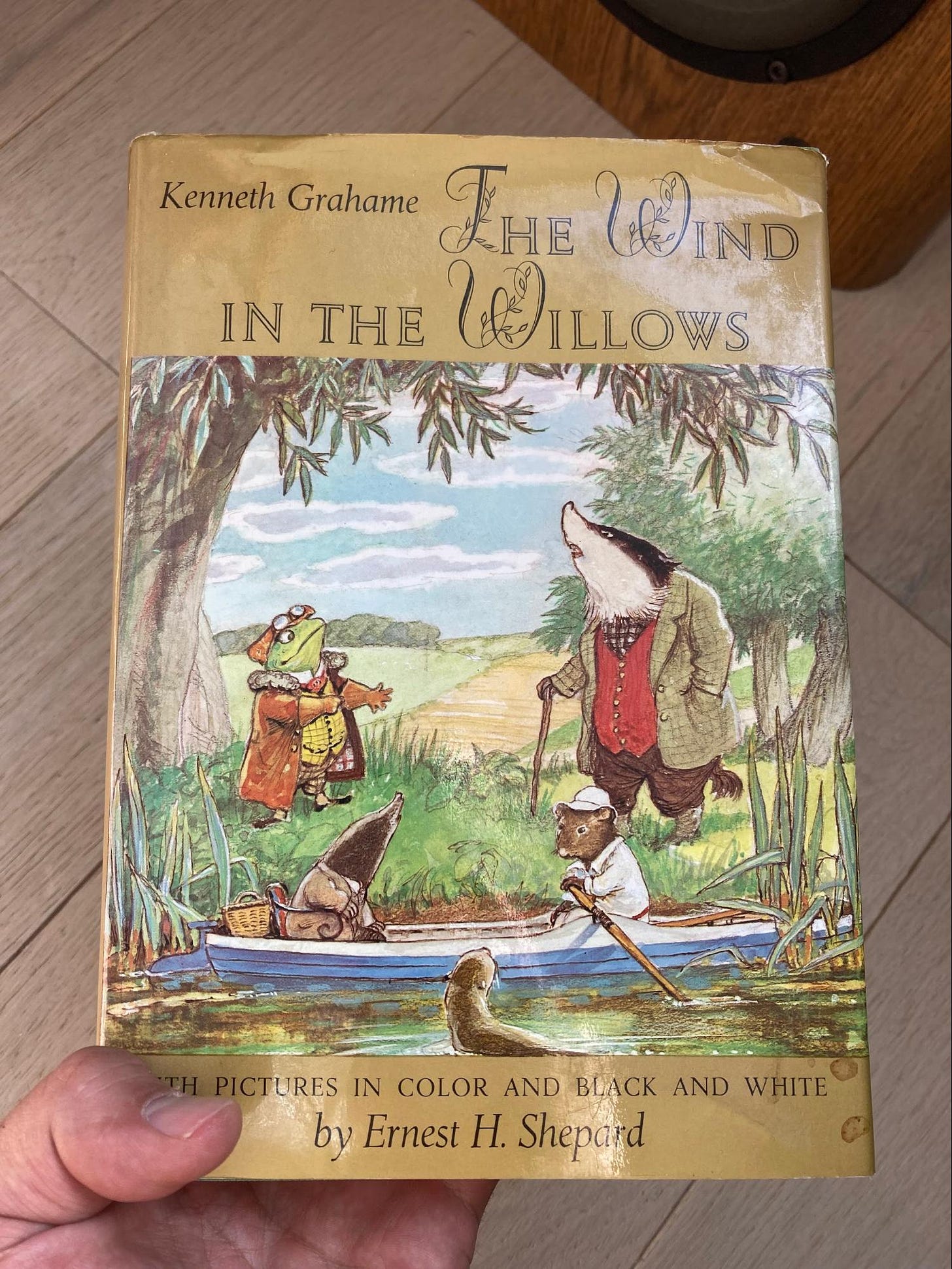

I started writing my folktale, The Tiny Horse, with plans to do like Rodari and change gears from “Once upon a time” to something modern, and two books I enjoyed as a child came to mind—The Mouse and the Motorcycle by Beverly Cleary, and The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, illustrated by Ernest Shepard.

The Wind in the Willows written by Kenneth Grahame, illustrated by Ernest Shepard (1908)

Only having a copy of the latter handy in my library (a copy I acquired to check on some wild theories my author-friend Mac Barnett had posited about the timeline of the book), I reread how Mr. Toad gets blindsided by the sudden existence of motorcars, unable to utter anything but “poop-poop.” (His interpretation of the sound of an automobile.) Yet for all the high speed car wrecks from my memories of the book, illustrator Ernest Shepard renders not a one, and mostly Kenneth Grahame prefers to describe the contents of picnic baskets, with most of the twisted metal happening away from the narration. In fact, I think Disney, and Disneyland specifically, are responsible for reframing Mr. Toad and his Wild Rides as the book’s central engine. In any case, I imported a car (a wrecked one) into my story (and intended to illustrate it). At first, I drew a more vintage buggy, but the anachronistic surprise of a modern machine in a fairy tale worked even better with a modern car, the design of which I find annoying, and thusly, more enjoyed smashing on the page.

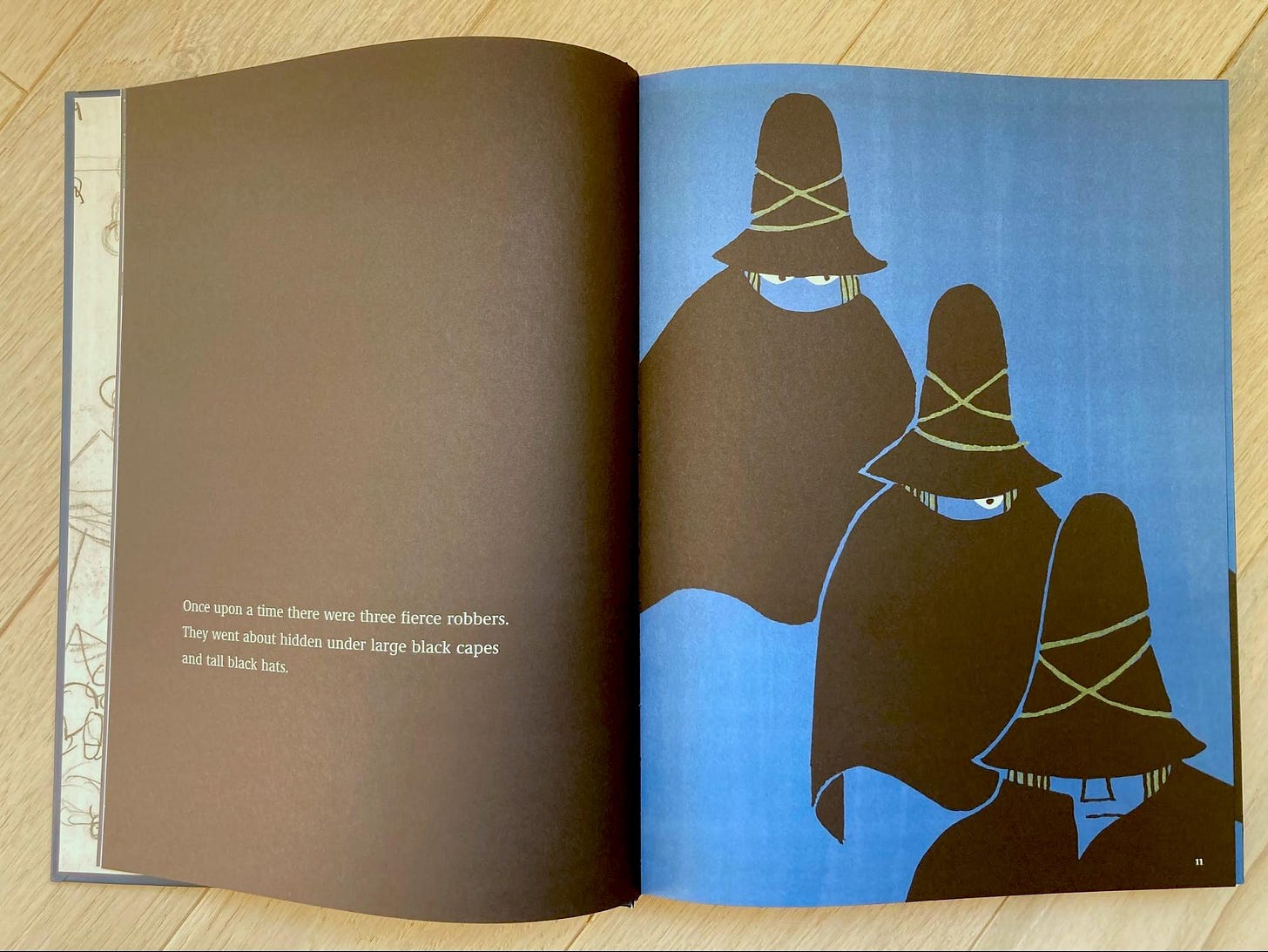

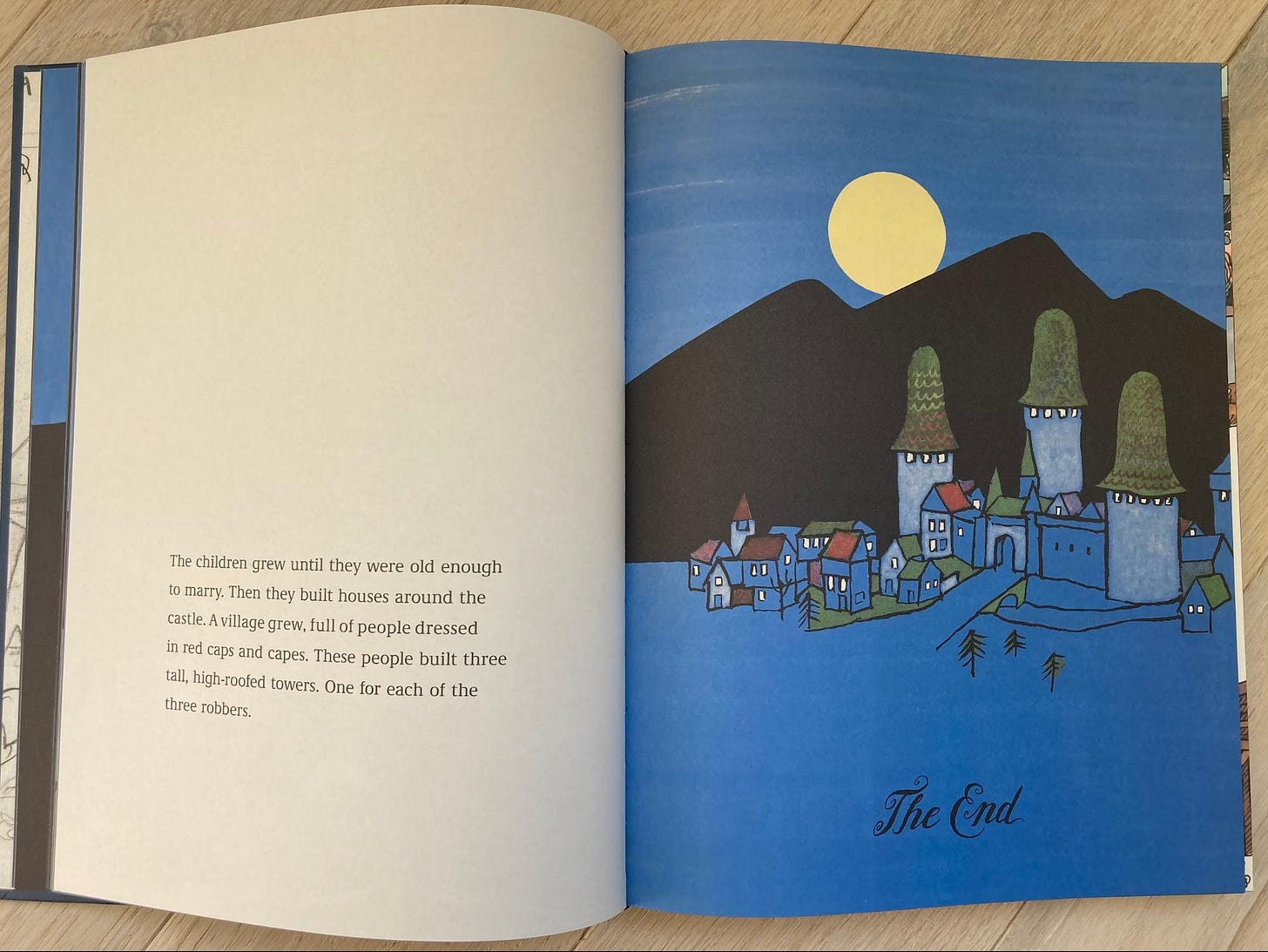

The Three Robbers by Tomi Ungerer (1961)

At first, I special-shelved this book for the illustrations, which are rendered in a limited palette: bold primary colors and a lot of black. I did the same, limiting my colors to just five or six tones, though I selected a more springy, pastel spectrum gathered around the neon spot color I used for my main character—who, by this time, was “teeny-weeny” instead of “tiny,” and upgraded from a “horse” to a “unicorn”— a change that gave me the idea for the opening line of the book that sets the scene as “…a land where horses are mythical beasts, found only in the pages of books for children…(but it was common to see a unicorn.")

But there’s also something about the tone of Tomi’s text I wanted to channel, too. Amidst the blunderbusses and highway robberies, there’s a very tender heart to his text. The result is rich—a happy ending in which our three main characters have also presumably died, but Tomi doesn’t sour things up and put death in our face either—it’s only there if we’re ready for it. And he doesn’t over-moralize and make it all too sweet.

It’s a rare dish—perfectly balanced and complex with every flavor. While my book doesn’t have a flavor profile quite this complex (nope, nobody dies), I did endeavor to combine flavors like Tomi might for a thicker stew.

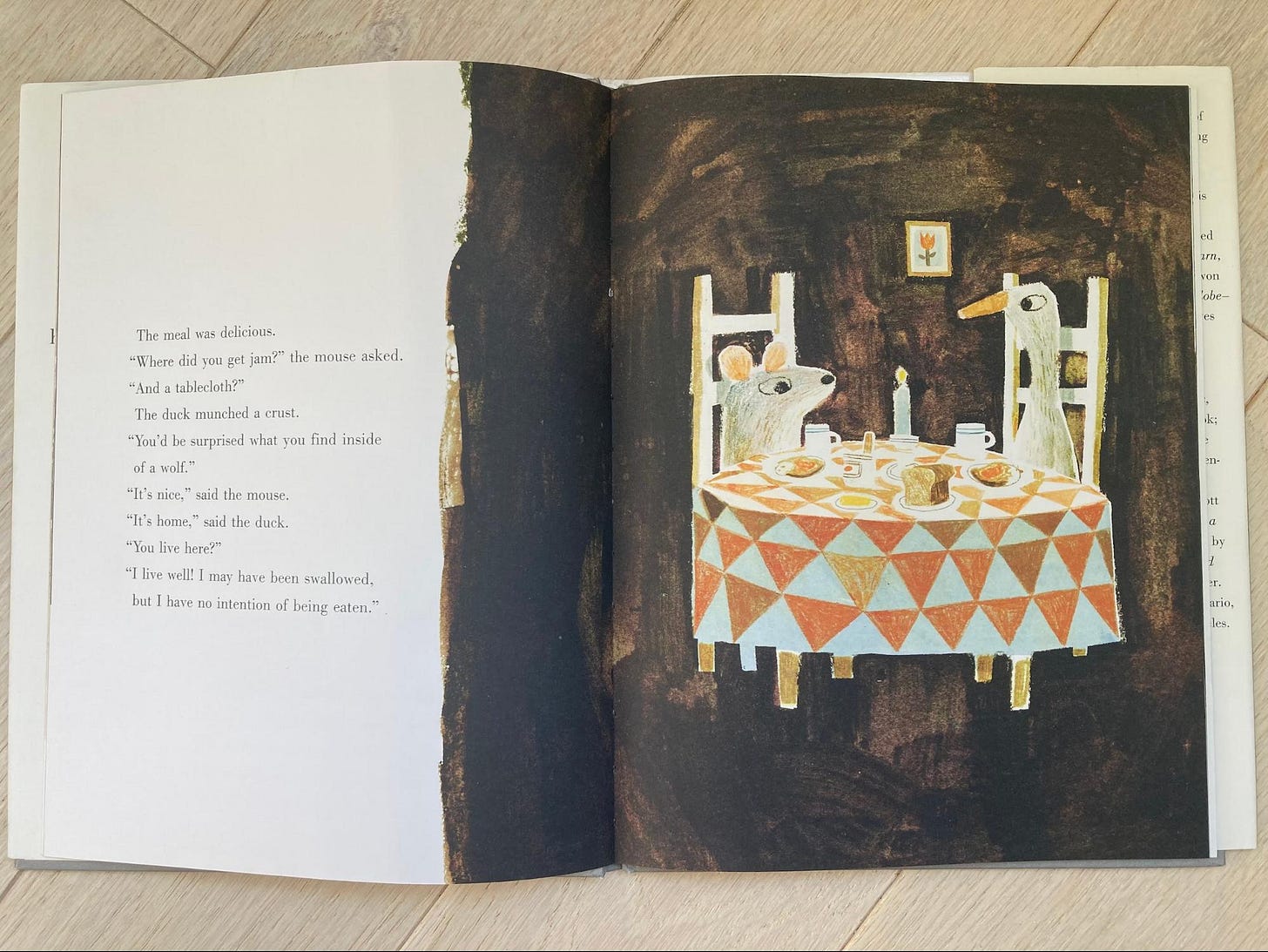

The Wolf, the Duck & the Mouse written by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Jon Klassen (2017)

There’s usually a book by Mac or Jon, and often one they’ve made together, on my special shelf. They’re just good at making books for kids, and they’ve made many at a very high quality for the past two decades. They’re also good at friendship, and sometimes, when I’m stuck writing or drawing, I call one of them, and invariably, they get me unstuck. This selection is a page I had clipped open from their original fable.

Aside from hoping that Jon fabricates and sells this tablecloth on his webstore someday, I love the looseness of his textures here. My brain fills in all of the surrounding furnishings of the wolf’s belly in that scrawly brown. I, too, wanted to leave big textural spaces for the viewer to imagine a world.

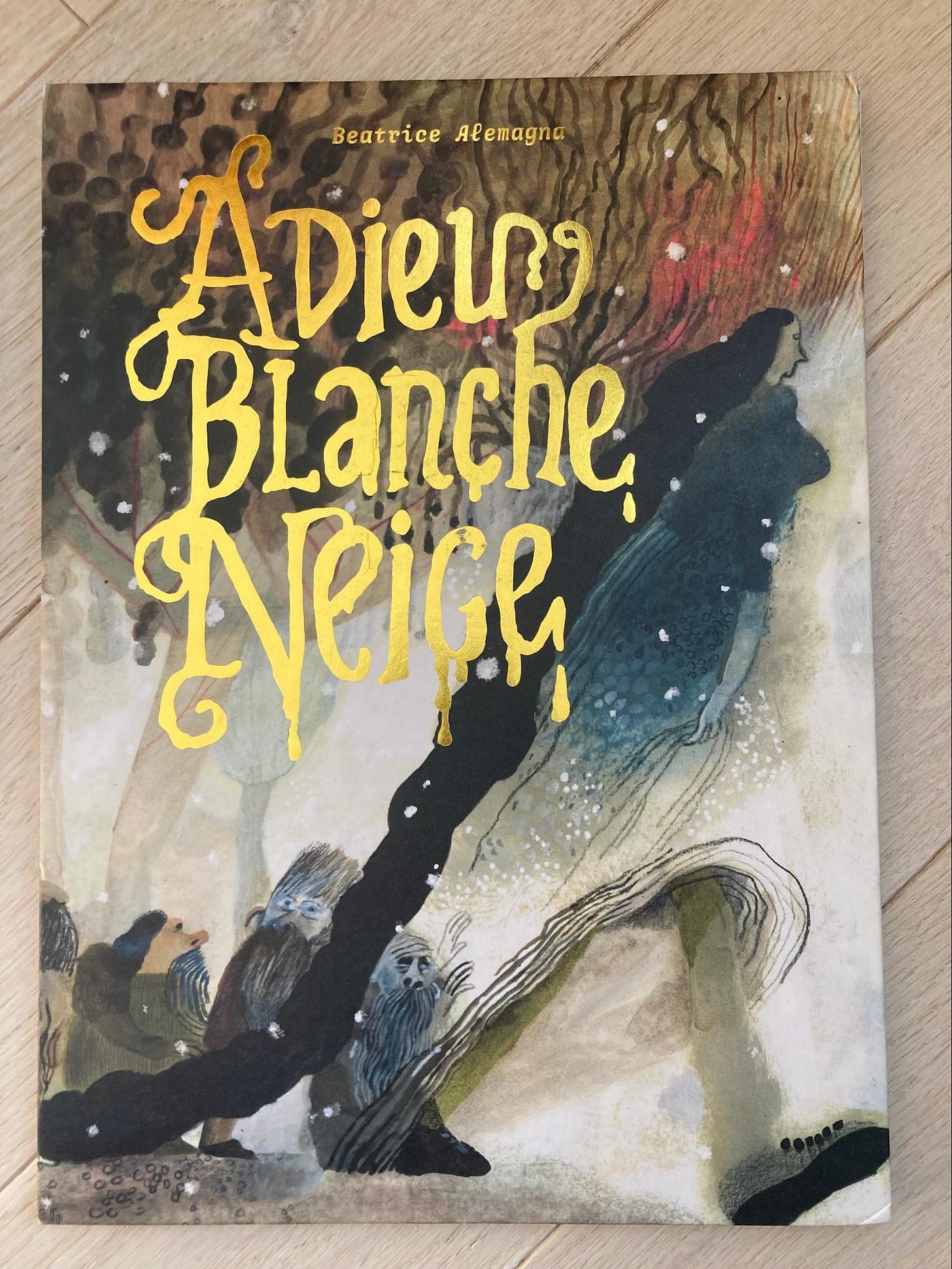

You Can’t Kill Snow White by Beatrice Alemagna (2022)

I anxiously bought this book in French before the English translation was published. Similar to how Klassen’s texture makes my brain play and fill in the world, Beatrice’s loose paintings in this one are an even more amplified example—toes on the line at times between representational and abstract art.

The familiar fairy tale she’s retelling becomes a truly strange and foreign affair with this treatment.

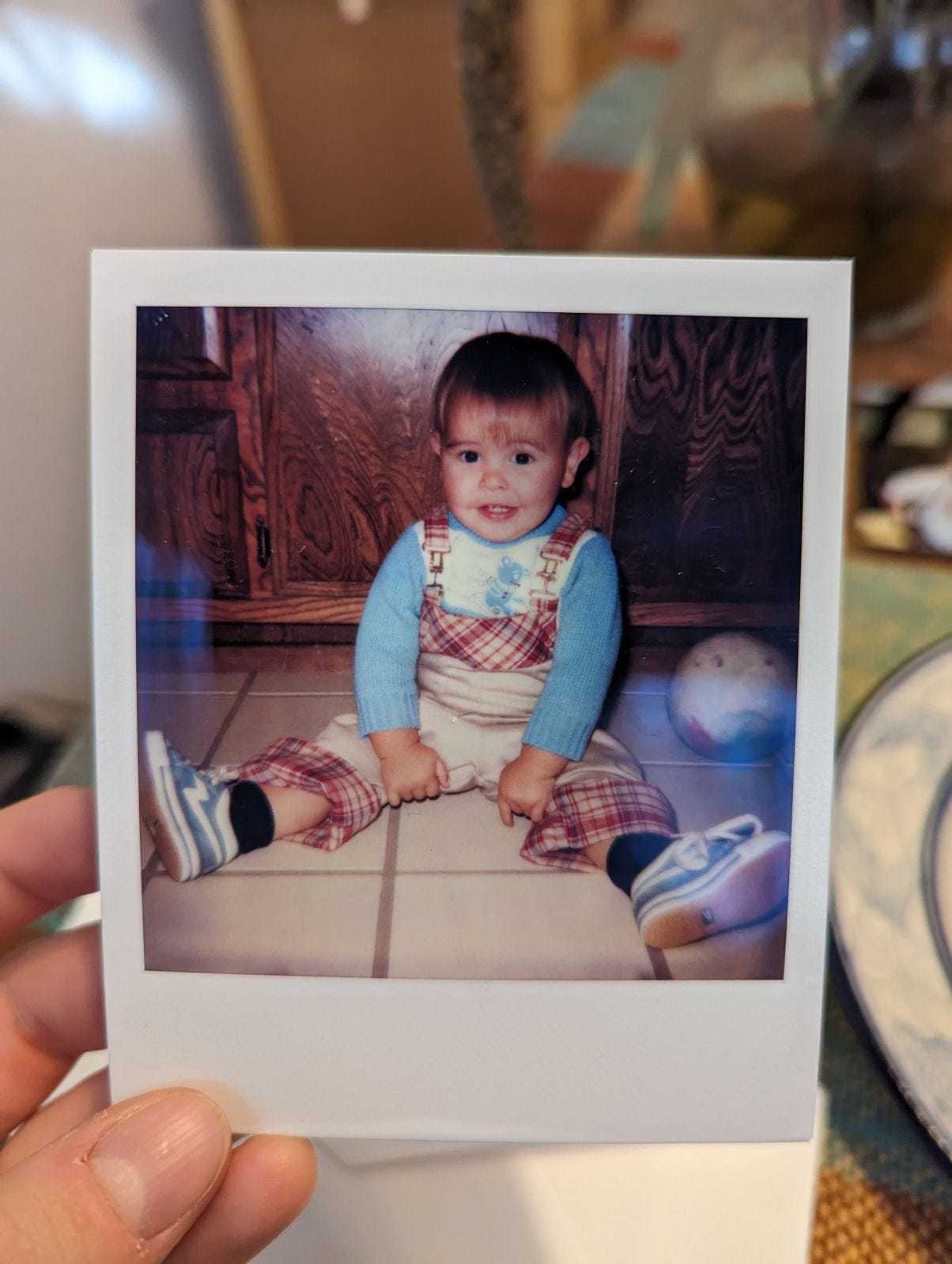

I did look around quite a bit for a book done in chalk pastel (the medium I chose to work in, based initially on color), and though I found a couple, none of them were much in dialogue with the flatter, blocky, yet smudgy way I was wanting to use the chalk. I pictured my book with gauzy, hazy, smudged edges—not many fine lines, and not much sharpness. I wanted it to look like the remembrance of a dream, or a Polaroid from childhood. Beatrice’s book was the closest I found to that idea, and though our books convey dissimilar moods, hers was a constant reminder for me to lean into the smudge and away from crisp renderings.

Speaking of Polaroids from childhood, indulge me in this top-speed hairpin turn in which I conclude by sharing this photo of my teeny-weeny self:

Thanks, Shawn!

Check back tomorrow for “Getting to Know Shawn Harris Pt. 2” (the podcast)

Hermann Hesse’s fairy tale Iris was part of the inspiration for Have You Ever Seen a Flower?” which Shawn and I walk about in “Getting to Know Shawn Harris Pt. 2”

OK, so he wasn’t entirely unknown! He was in a popular rock band!

Ursula Nordstrom is a legendary children’s book editor. Check out the great book Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom by Leonard C. Marcus (2000)

SO GOOD. I just love this. When I saw that shelf shot, my immediate thought was, "You and Shawn have the same taste." That is a very Taylor Sterling assortment of titles 😊

(And, weirdly timely: two days ago I was anxiously scouring for books about being/feeling small -- we're going through stature-related stuff right now -- and it's such a weird category, there's not a lot of options, so thank you for The Teeny-Weeny Unicorn, which was not on my radar.)

Verrry choice picks 🤌 Love having an inspo shelf immediately in front of you while working, like a living moodboard.