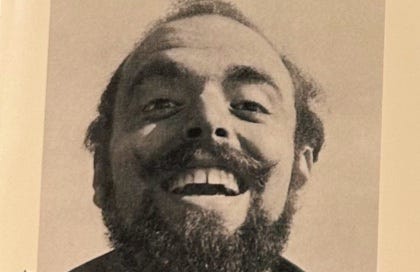

Shel Silverstein's Hot Hipster Author Photos, the Cruelty of Roald Dahl, & Sesame Street Songs

5 things to check out this weekend!

I’m back with another 5 Things! This is my recommendation series of five things to read, listen to, and watch—usually centered around children’s literature, but sometimes it’s other art forms made for children. Like always, there are five main recommendations, each with a set of offshoots for you to explore. But what’s different about this edition is it's for paid subscribers only!

I’m testing out this series as a special bonus for my paid subscribers. If you enjoy reading Moonbow and are debating becoming a paid subscriber, this would be a great time: You’ll get access to every one of Moonbow’s newsletters, including 5 Things, and future paid-only articles coming this year.

Thanks for your support!

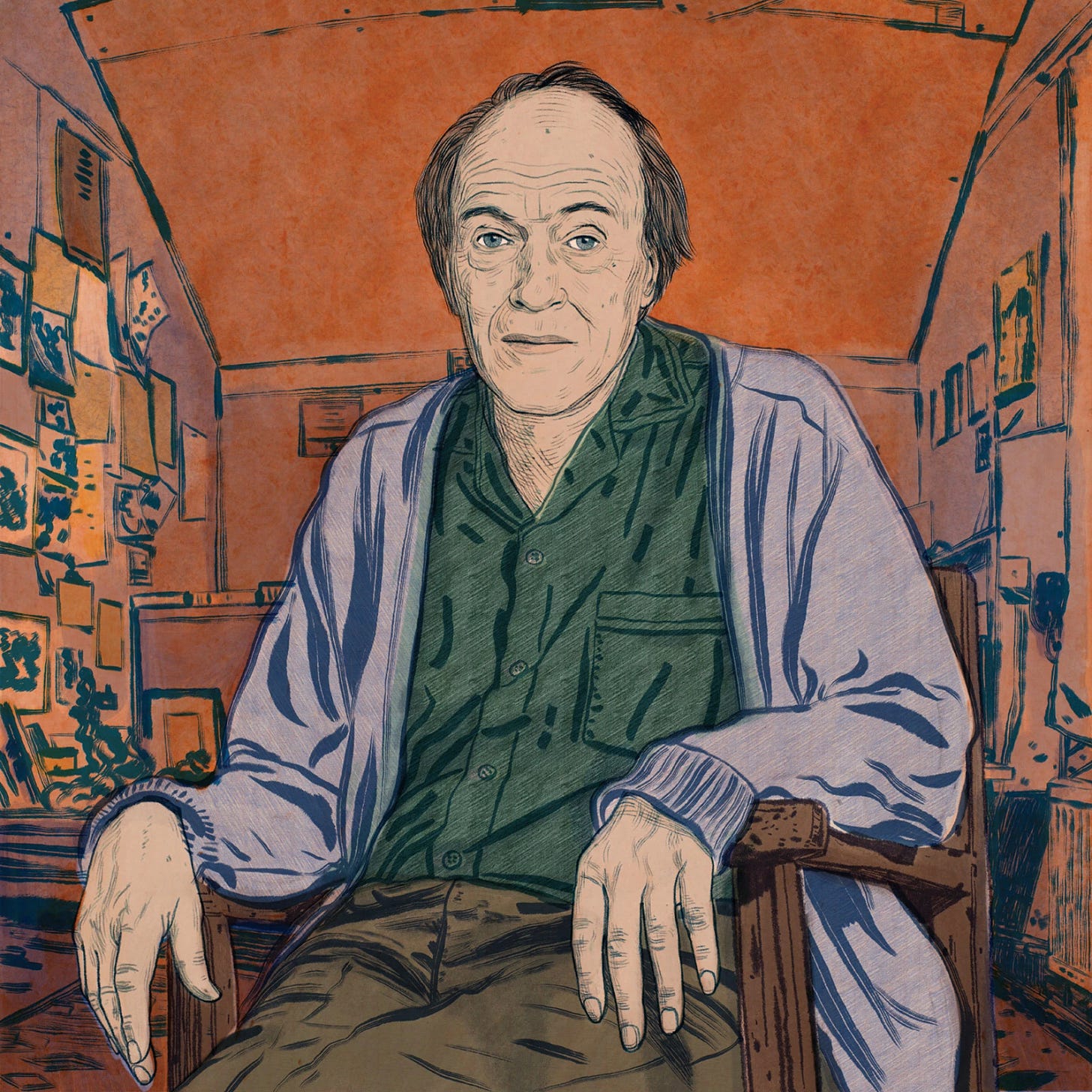

Roald Dahl’s Matilda (1988) was an important book to me growing up. It’s still important to me. It’s one of the only children’s chapter books I reread every year, with or without my kids. The character of Matilda represents everything I aspired to as a young girl: bookish, creative, resilient, and kind. She’s mischievous but never cruel. Like Matilda, I often felt misunderstood and isolated—and I bravely, and often naively, questioned authority. But the book isn’t without faults, as with most of Dahl’s books. Many of his books contain offensive racist and sexist phrases and an overall mean-spiritedness. Reading them, especially in succession, can sometimes leave me exhausted and depressed.

I wonder: Do I love Matilda the most because it was heavily reworked by Dahl’s editor Stephen Roxburgh? Dahl’s first draft of Matilda was wickedly nasty. It was Roxburgh who shaped it into a more nuanced and satisfying story. This revelation has me thinking about the current trend of revising upsetting language in classic books. It feels wrong. My approach to reading old literature that doesn’t meet our contemporary sensibilities is to question it, not erase it. When my kids and I read offensive language in books, we discuss it afterward. It’s a way for us to communicate with each other about the true ugliness that exists in our world, which will remain even if we edit it out of books. Art is a place for us to explore cruelty, bigotry, and hate, and if we smooth over all those rough edges, how will we know how to handle it when someone is horribly nasty to us? It’s a nuanced debate, for sure. I recognize that editing them has some benefits. Would I have adored Matilda as much in its original draft? It’s hard to know, but my guess is probably not.