One year ago, I felt like a deflated balloon; a balloon struck by a sharp knife; quickly and aggressively losing its air, but not all of it; the rest slowly seeped out, and with each sad little loss of air, I became increasingly limp and pathetic. Dramatic simile, I know, but it’s pretty accurate for how I was feeling at the time.

During the middle of the pandemic, while juggling all the things, I experienced a personal blow that forced me to close my decade-old business. It was a sucker-punch hit, and it took several months (which felt like years!) to “recover”. But it was time for me to start looking for work, something I hadn’t done since 2006—which may as well have been forty years ago—that’s how different searching for work feels now. As expected, finding a new job after happily working for myself for ten years felt daunting and depressing. I didn’t know how to write a resume (I still don’t), and every time I wrote a cover letter, I felt another crucial loss of my creative air supply. Thankfully, and not-so-thankfully, no one seems to read your resume and cover letter anymore, even though you’re obliged to rewrite them every single time.

After a few disheartening months, with no real prospects in the works, I decided I needed to create something that I could have complete creative control over, something that would keep my spirits up while I looked for the new job I didn’t want. But it couldn’t be another version of Glitter Guide. As wonderful as that experience was, I was ready for change. At the time, I’d been enthusiastically sharing children’s books on my Instagram, and it was becoming increasingly interesting and exciting to me. But I wasn’t interested in simply reviewing new books. I wanted a space to explore children’s books as an art form. I wanted to learn its history, find compelling connections, and introduce readers to new ideas. I wanted openness. But the ironic thing about Moonbow is that its freedom is sometimes limiting. I’m not catering to a set audience or following conventions; I’m letting curiosity call the shots. Each newsletter is different, and there is no clear way to market this material. In a year, I’ve hardly ever put up a paywall on my newsletters. Making you pay to read my work is counterintuitive to me. Whenever I try to think of content that justifies a paywall, I cringe: that’s not openness! (Although earning more money for my time would be nice.)

Also, Moonbow is difficult to describe. I say that it’s a newsletter about children’s books, but that’s not entirely true. Children’s books are at the center of everything I write, but it’s rarely about specific stories, and when it is, it’s things connected to the book more than it is about the plot, if there even is one. I’m more interested in finding ways to articulate what these books and their authors are doing and why it works, literally and symbolically. At the risk of sounding narcissistic, my motivation is to find something seemingly trivial or obscure—a secret interest that no one cares about—and show you why it works and is important.

I recently listened to a podcast from Vox Longform with the writer Sam Anderson that resonated with my writing motivations more than anything I’d ever encountered. In the interview, Anderson talks about this type of narcissism. When the interviewer asks Anderson the difference between when he writes about obscure artists—ones who are typically outside of national consciousness, like: "Weird Al" Yankovic, Sharon Olds, Anne Carson, Laurie Anderson, John McPhee, versus when he writes about well-known figures like Kevin Durant or Drake, Anderson replied candidly:

“[When something] reaches that level of cultural penetration…there is something about it that’s kind of intoxicating…maybe this is narcissistic…a lot of what I’m grappling with, especially lately, is narcissism, and how many of my thoughts about the world are just because I’m like putting myself in the middle of it, and maybe even the writing subject choices are about that. Maybe it’s like, ‘I have to show everyone how special I am by choosing things that they aggressively do not care about and forcing them to care. I need to overpower all of their instincts of interest and how to spend their time as a human on planet earth, and I am going to drag them over here against their will.’ Yeah, maybe that’s like the ultimate sort of narcissistic move rather than just be like, ‘Oh, everyone is interested in this; let me say some cool things about it.’”

Similarly, I often think: Does anyone care about this? And then I stubbornly, and perhaps arrogantly, write about it anyway. But it’s not as much arrogance as it is a challenge. Often I’m convincing myself of what I’m writing about just as much as I’m trying to convince you. Maybe “convince” is the wrong word; maybe it’s “influence"? Anderson mentions the tradition of old English essayists, like G.K. Chesterton’s All Things Considered, where Chesterton chose provocatively trivial subjects and tried to make them fascinating, or John McPhee’s brilliant book Oranges, which is all about oranges (yet so much more).

“It becomes almost like experimental literature at that point where the hurdle is to get people to care about this thing. And I love that. There is a kind of impish little rebel in me that doesn’t want just want to write about the obvious and popular thing that people are already interested in because that’s too easy, and what I want to do is yank people over to areas they would never want to look otherwise.”

I’m not claiming that children’s books are trivial, but they aren’t usually considered sophisticated works of art, and to be fair, not all are—just like with any art form. But unlike other forms, the artists of children's books are often thought of as cute and sentimental when they rarely are. Everyone thinks they can write a children’s book. Yet, those of us who spend a lot of time with this art form know that, yes, everyone can write a children’s book, but hardly anyone can write a great children’s book.

So that’s been my driving force this past year: to help people see why children’s books are fascinating, important, weird, poetic, difficult, experimental, and delightful for kids and adults. I hope I’ve inspired you to look at these books with a fresh perspective. In year two, I plan to chase more white rabbits down mysterious holes, and hopefully, you’re excited to be a part of that adventure. I won’t give this a tidy, predictable ending: I’m not a plump, full balloon now; that would be a lie (and cheesy). But Moonbow has been creatively fulfilling this past year, and I can’t wait to see where I float off to next.

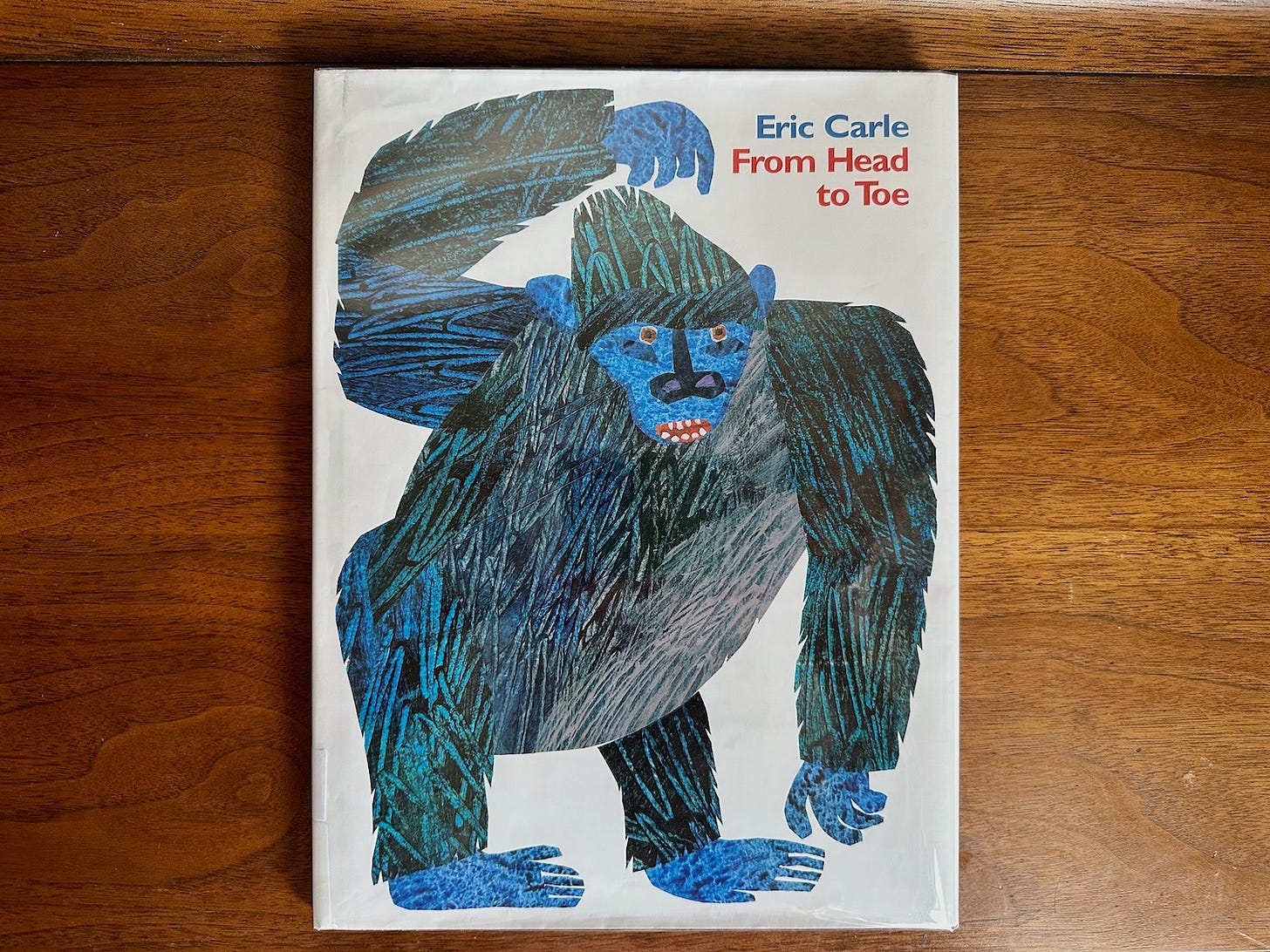

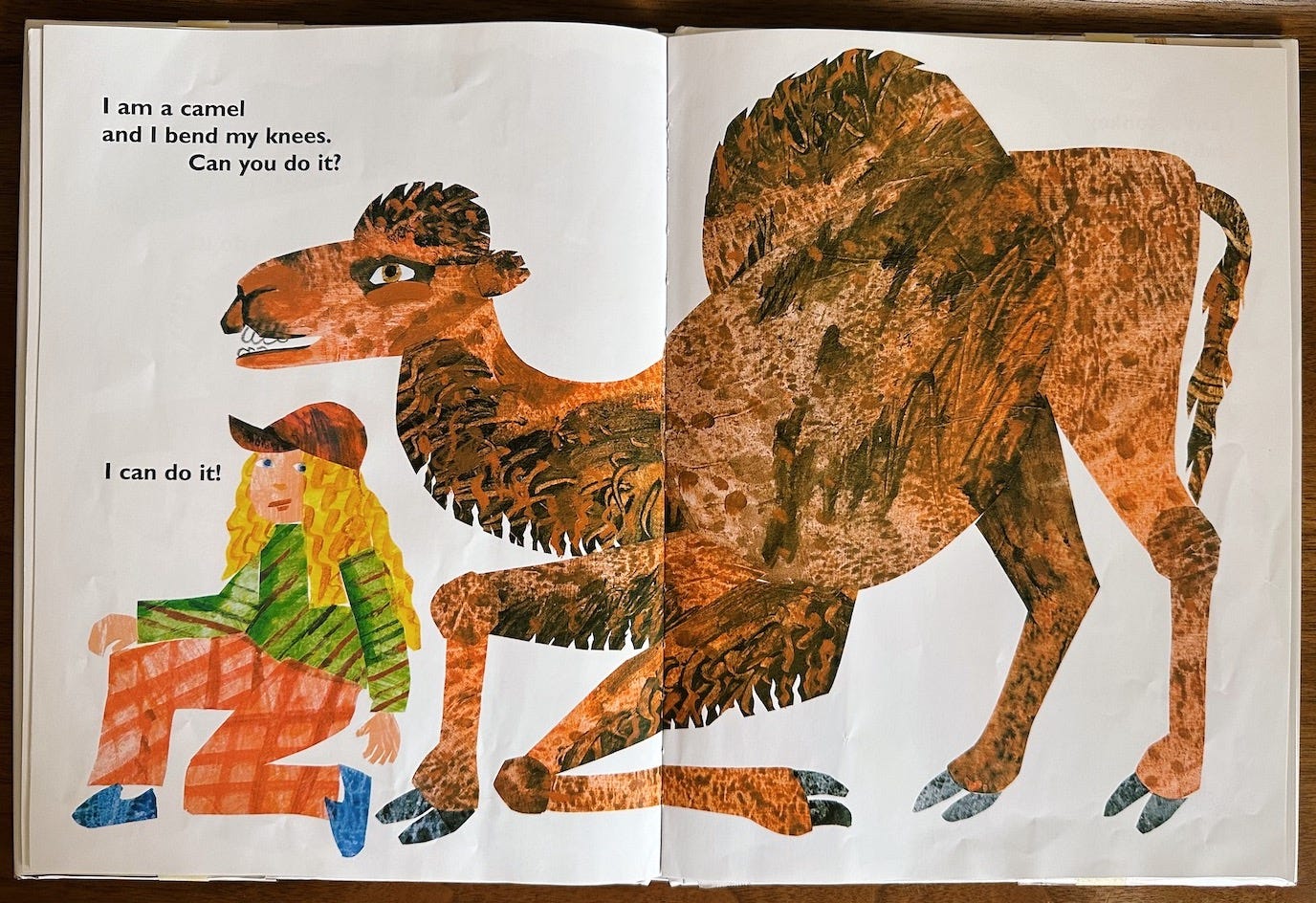

We Can Do It!

LOOK! I found myself in Eric Carle’s Head to Toe! And like that girl, and the other competent kids in the book, I CAN DO IT! But it would be easier if I did it with your help. Writing Moonbow takes a lot of time and resources. Having paid support means I can continue to do it! As I mentioned, most of these newsletters have remained free to read. I’d love to keep it that way! But as I move into this second year, I have to find ways to make it more profitable. I think I’ll create paid content in the future, but in the meantime, consider a paid subscription like a donation. It keeps these newsletters consistent and free from advertisements. But more importantly, it shows me you value my work.

I write these articles between my freelance work and usually on the weekends. Without paid support, it’s unlikely I’ll be able to continue to create Moonbow content in the future, or at least consistently—and that would be a bummer.

For a limited time, I’m offering a Founding Membership for $100/year or for any price you can donate. You can put in any amount that you’re comfortable with. Plus, I’m working on new Moonbow merchandise goodies, and becoming a founding member means you get first access to all things Moonbow!

I made the MOONBOW MIXTAPE available to everyone now! Listen to the funky mix of songs that inspire Moonbow.

And a HUGE thank you to my current paid subscribers. You helped turn this year around for me. Thanks for your support!

I’ll end this celebratory newsletter with an interview I came across in The New Yorker. It’s hilariously perfect; I can’t stop thinking about it!

Kid Critics: Sam, Age 8

How do you choose your books? What makes you think that a book might be good if you’ve never read it before?

By the cover, and by people saying it’s good or bad.

What do you look for on the cover?

A funny face.

Where do you get your books? The library? A bookstore?

My house.

Share this post