Gyo Fujikawa: The First Children's Illustrator I Fell In Love With

It happened the night before Christmas

My favorite day of the year is the night before Christmas. I prefer it to Christmas Day, always have. I enjoy the anticipation and wondering—the twinkling excitement of what’s to come. It’s also the night I first fell in love with a book.

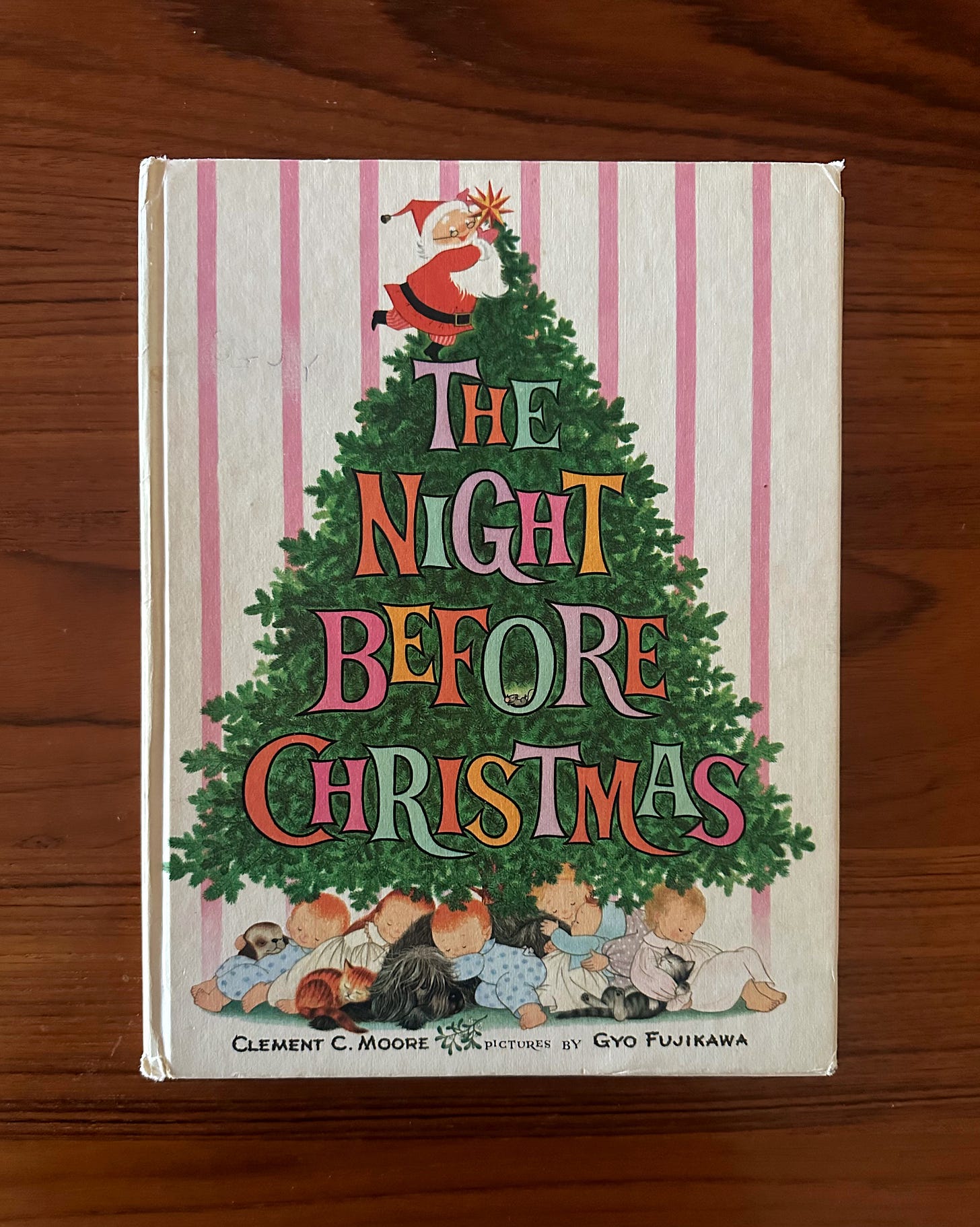

Every year, on Christmas Eve, my parents read me The Night Before Christmas by Clement C. Moore. The iconic holiday poem, originally titled "A Visit from St. Nicholas" (1822), has charmed readers for hundreds of years and has many different illustrated interpretations. Ours was a 1961 picture book illustrated by Gyo Fujikawa.

There’s a good chance I loved other books before this one, but I don’t remember them. The only other book I remember from when I was very little was My Goodnight Book (1981) by Eloise Wilkin, a sweet but monotonous story about a little girl’s bedtime routine. I only remember it because my parents read it to me ad nauseam (and I still own it). But The Night Before Christmas was different. Most of the year, it lived in a dusty old box in the attic with all the Christmas decorations. It only came out during the holiday, and we only read it at night on Christmas Eve. It was our special, festive family tradition, one that I’ve continued with my children.

As a child, I found Moore’s famous poem comforting. I had mixed feelings about Santa. He was a fantastical figure I adored but also feared. I mean, he’s always watching me? And he sneaks into my house at night while I’m asleep to leave me presents (or coal if I’ve been bad!). Santa is kind of a weird dude. But The Night Before Christmas assuaged my anxiety over St. Nick, especially the reassuring line:

“A wink of his eye and a twist of his head. Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread.”

Now, as an adult reading it to my children, my uneasy feeling isn’t toward Santa but toward Clement C. Moore, a racist who owned slaves. Still, even as a child, it was less about Moore’s poem and more about Fujikawa’s enchanting illustrations.

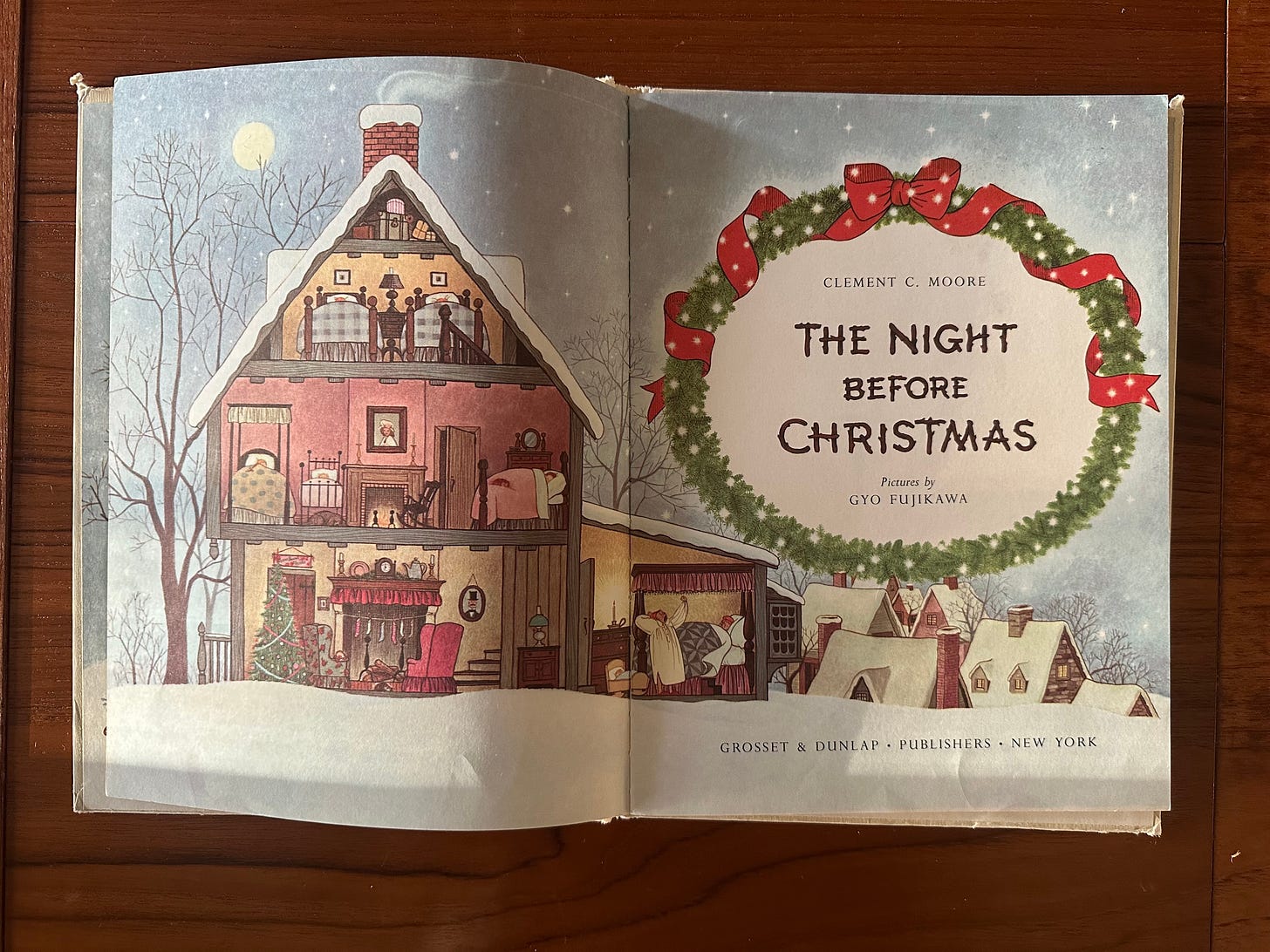

I remember falling in love with the pictures before the story even began. When you open the book, you’re greeted by a soft, snuggly, snowy Christmas Eve night. A stunning cross-section of the house gives a sneak peek at the family right before Santa arrives. The stockings are hung by the chimney with care, the children are snug in their beds while visions of sugar plums dance in their heads, and the parents are about to settle their brains for a long winter’s nap. Of course, if you’ve never read the story before, you don’t know these delightful details, but once you do, it’s fun to go back to this spread and think about them.

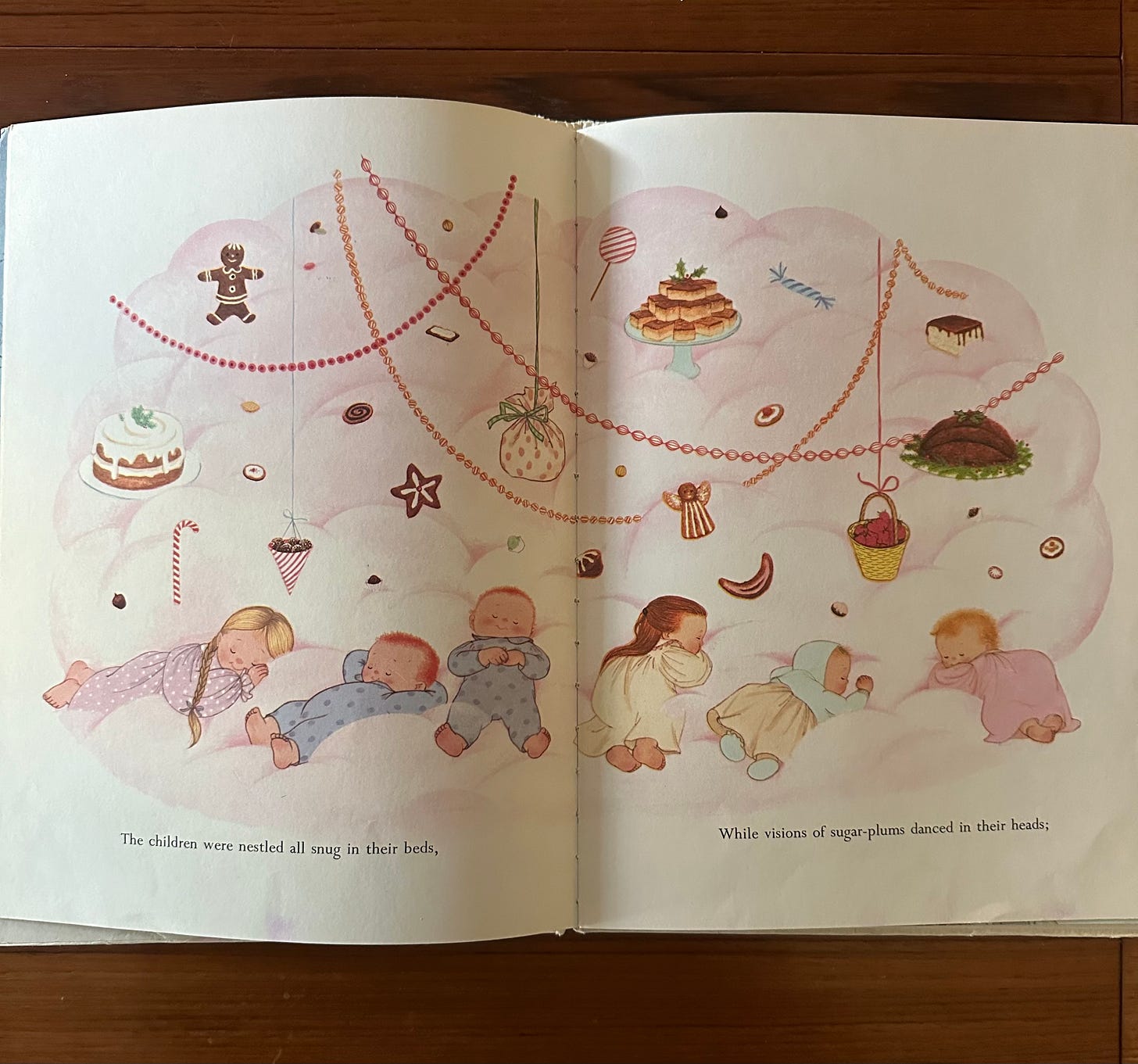

As a child, I loved the three lively page turns of Santa’s arrival as he flies through the beautiful—midnight blue, then pink, then blue again—sky in his sleigh with his reindeer as the bright full moon hovers over him. And the spread where we see the many sides of Santa: mischievous and silly with his cherry nose, droll little mouth, and little round belly. But my favorite was of the children dreaming of dancing sugar plums. It captures the indulgent fantasy of Christmas Day that I felt so acutely as a child (and was often let down by).

Looking at Fujikawa’s pictures, I realized for the first time that someone was behind them, and I took note of her name to search for more books with her magical pictures. Thinking back, this was unusual. Most of the time, I didn’t acknowledge the authors and illustrators of my favorite books. Sadly, despite Fujikawa’s commercial success and popularity among children, she remained largely unknown (and still does). This is partly because she was a product of a different time when there weren’t many celebrity children’s authors and illustrators, but also, she was an Asian American woman; sexism and racism contributed to her invisibility.

Gyo (pronounced "gy-oh") Fujikawa was born in Berkeley, CA in 1908. As a young girl, she loved to draw and was good at it. Eventually, her talent caught the attention of her teachers, who helped raise money for her to attend art school. At 18, she moved to Los Angeles to attend Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts), where there were few girls and even fewer Asian American girls. It wasn't easy, but Gyo focused on her drawings. After college, her hunger for knowledge led her to travel the world, but when it was time to start her career, she moved back to California. She landed a job with The Walt Disney Company, where she created promotional materials. In 1941, she permanently moved to New York City. Just as her career was starting to take off, World War II began, and many West Coast Japanese and Japanese Americans, including her family, were forced to live in internment camps for the duration of the war. Gyo was heartbroken, but her anger and grief made her even more determined to draw her and her family toward a better life.

In the 1950s, Fujikawa began working as a freelance artist, drawing for magazines and doing commercial work. She also illustrated a handful of picture books, such as A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson (1957) and The Night Before Christmas (1961). Both represent what we now recognize as Fujikawa’s distinct style with soft, vibrant colors and children with sweet, expressive faces and wonderfully round heads. However, there is one notable difference: the children are all white.

Sick of seeing stories with the same-looking children doing the same boring things, Fujikawa had a revolutionary idea for a book that showcased babies of all shapes, sizes, genders, and races, but no one would publish it. In the early ‘60s, America was still segregated, and so were the books. Infuriated, she pleaded with publishers, pushing them to make a change. Thankfully, they did, and in 1963, Fujikawa’s Babies was published. The book was a huge success and sold millions of copies, proving that children need and want to see themselves in books.

At the time, most illustrators were only offered flat fees for their books. It wasn’t easy to make a living (it still isn’t), and artists had to take on side hustles to get by. But being the trailblazer and savvy businesswoman she was, Fujikawa fought for royalties—and won—making her one of the first children’s book artists to receive them. She transformed the industry standards for the better, something she doesn’t get enough credit for.

After the success of Babies, Fujikawa continued making books—50 of them!— including all sorts of children doing all sorts of things. Like her contemporary Richard Scarry, her books are busy, full of swirling movement and intricate details, but there are also moments of soft tranquility. She was incredibly prolific during the ‘70s and ‘80s, publishing over 40 books, 16 of which came out in 1981. I think this is why the children of my generation (I was born in 1982) are so fond of her books. We grew up with A to Z Picture Book (1974), Fairyland (1981), Here I Am (1981), Mother Goose (1981), and so many more.

I fell in love with Fujikawa’s artwork because of The Night Before Christmas, but it was Oh, What a Busy Day! (1976) that turned me into a superfan. It captures a day in the life of children, from morning until night, filled with sonic onomatopoeic delights, playful rhymes, jingles, and imaginative ideas. Like many of her books, it alternates between full-color and black-and-white spreads, emphasizing specific elements and creating a nice visual contrast. (It also saves printing costs.)

It’s a fun and interactive book with expansive scenes of children playing in parks, treehouses, gardens, and under beds. There are also children reading books, napping, watching television, and blowing bubbles. Sometimes, the children are happy, and sometimes, they’re sad. It’s not excessively twee or nostalgic about childhood. Instead, it refreshingly depicts a wide array of children’s interests and moods.

One of the first and most memorable spreads is the breakfast picnic scene. It has one of the funniest little poems.

Then a great, big breakfast!

Through the teeth,

Past the gums,

Look out, stomach!

Here it comes!Mother, dear,

I sadly fear,

My appetite,

Is always here!

And there is so much to look at—even a mama dog feeding her pups! Look at the kid eating under the table. We all know that kid. I have that kid.

Despite being my favorite Fujikawa book, I hadn’t read it in years. Revisiting it, I remembered how remarkable it was, and I recognized its influence on many contemporary children’s books, like this illustration in The First Cat in Space and the Soup of Doom (2023), and especially Julie Morstad’s How To (2013) and Today (2016).

In 2019, Morstad illustrated It Began With a Page, an inspiring picture book biography about Fujikawa written by Kyo Maclear. Shockingly, it’s the only book published about Fujikawa’s life and art. Morstad and Maclear are two of the best in the biz. They ingeniously captured Fujikawa’s exceptional life. However, I couldn’t help but feel sad that there isn’t more written about her. There is no merchandise, exhibitions, or documentaries—and I couldn’t find a single one of her books at any of my local library branches. How can someone as revolutionary and iconoclast as Fujikawa be so invisible? (I think we know why.)

Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day was published in 1962, one year before Fujikawa’s Babies. Both helped pave the way for more inclusive and diverse children’s literature, but Keats, a white male, gets most of the credit. Don’t get me wrong, I love Keats’s books; I just wish Fujikawa were more well-known for her outstanding achievements.

Fujikawa died in 1998 at the age of 90. Throughout her life and career, she challenged conventional ideas of gender, race, and storytelling. Her art opened my eyes to the magical world of books. It inspired me and made me laugh; it still does. In Oh, What a Busy Day!, there’s a picture of a little blonde girl hiding in a leafy burrow, gazing happily at the animals around her. The text reads, “And then there’s my own top-secret place. Don’t ask me where, for I’ll not tell. It’s my very own, my secret hideaway!” Fujikawa’s books were my secret hideaway. But I don’t want them to be a secret anymore. I’m inviting you in. I hope you’ll join me.

I loved her work so much as a kid, influenced by my mother's love for her illustrations. When I was pregnant with my daughter I can remember my mom searching down Gyo's 'Mother Goose' because no other copy would do for her first grandbaby!

I don't think I realized how invisible she is, because we always had her books on our shelves. It makes me so sad to hear you couldn't find her books at the library! When I was a school librarian, her books were always part of my list of classics to make sure we had on the shelves.

She is one of my favorites too! We had the A to Z Picture Book growing up (and it’s still on my shelf today) and I remember just getting fully immersed in the illustrations. I think I felt like the scenes in the book were really accurate in showing how I experienced the world as a kid. Some of the scenes were bright and cheery, and funny, some were tranquil, and some were a little bit dark, and almost foreboding. Love how her images spread across the entire spectrum. She was SO good.